For the summer edition of our debut craft series, I spoke with the authors of three novels anchored by unnamed narrators who gather conversations like wild berries in a field. They forage for witticisms, one-liners, nuggets of ancient folklore, political creeds, and casual conversation. All that language is then wrapped into layered characters, drawing out the intimate stories embedded within each of them.

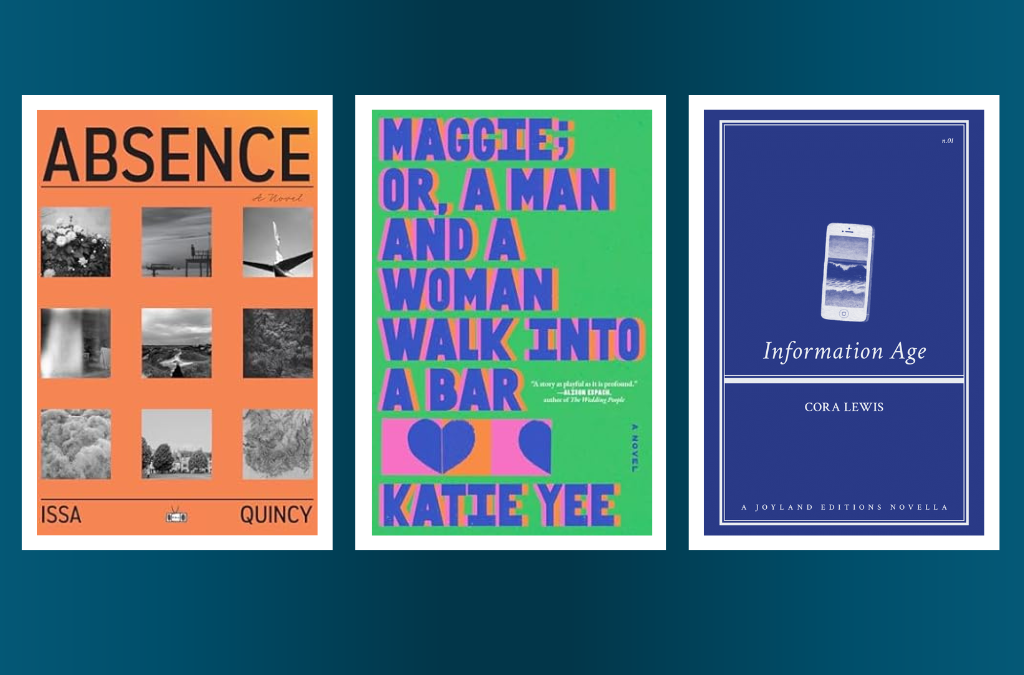

In Absence by Issa Quincy, the unnamed protagonist is an attentive listener and archivist who serendipitously stumbles upon the most emotional experiences in strangers’ lives and absorbs them into the canvas of his own. Sorting through old letters and photographs, the narrator remembers an encounter with a bus driver smoking on a Boston curb; another with a young, grieving landlord from his London past; an old friend’s ties to Cyprus; and a mysterious poem from his youth that continues to haunt him today. In combining rare, enthrallingly poetic prose with a decidedly detective-noir influence, Absence hints that perhaps the meaning of presence itself is an archive’s greatest mystery.

In Katie Yee’s Maggie; or, A Man and a Woman Walk Into a Bar, the narrator is an observant mother, nostalgic ex-wife, hopeful patient, and grieving daughter who gathers her mother’s Chinese folktales and retells them as bedtime stories to her children. Ultimately, she finds she is the one who needs to hear the old stories, and sharing them with her children becomes another way of hearing them herself. Throughout the novel, even as the protagonist contends with intense challenges—including a life-threatening diagnosis and a gut-wrenching divorce—Yee’s humorous prose glitters and manages to turn a tragic plot line into a punchline brimful of optimistic grandeur.

Finally, throughout Cora Lewis’s Information Age, an unnamed journalist based in New York embarks on assignments around the U.S.—she follows a Rust Belt campaign trail, attends candidate rallies, interviews strangers, tracks weather and wildfires, speaks with merch vendors, oracles, and young women at Waffle Houses. These snippets filter their way into the character and become sewn into her personal life—fragmented and constellated by dating and mid-twenties heartbreak. Bringing all these ideas and stories together, Lewis creates a snapshot of a life and a culture through a mosaic of distinct, profound voices.

In our conversations, Issa Quincy, Katie Yee, and Cora Lewis discussed the sparks that ignited their first drafts, the long and winding road of revision, the importance of characters’ names (or lack of names), coincidences, and the metafictional aspects of frame narratives.

Kyla D. Walker: Did you write the novel with an outline or ending in mind? Or were the characters’ voices and anecdotes the guide?

Issa Quincy: I have learnt, through successive failures, to never plan work beyond a very vague outline or a dim intuition of direction. As I begin writing, I often find myself quite drastically straying away from some of these things. The tension I require to create a work comes from the tension of discovery. For me, there has to first be an acceptance that one knows very little about what comes next in order for the act of creation to be engaging, to access the subconscious. There are multiple levels of interplay happening within an author as they write—most obviously, what the author intends and, in spite of this, where they’re being led. I once read somewhere that every work of art is the wreck of a perfect idea. I think this is largely true. I have found when I plot things out too clearly, when I know too much, I lose interest or a desire to continue working. Perhaps this is because the idea is already too perfect and I can see more clearly how I am wrecking it.

Absence was led largely by my dim intuition and what felt right for the novel as I went on. Much of the plotting, or the seemingly more intentional aspects of the novel (i.e. the ending) came during the revision process. I find you have to first see the unconscious patterns, motifs and images that emerge from your uncertainty, your unknowingness in the instant of writing, and only then can you begin to really make sense of it as an entire piece and retroactively mold it into something more coherent.

KW: Letters, journals, and photographs from the past play a significant role in the novel. The narrator of Absence at one point gets hired as a heritage museum archivist in Maine. I read that you too worked as an archivist. How did your work (and the narrator’s) as an archivist inform or influence the story?

IQ: My archive work gave me a lot of time to reflect on collective and cultural memory, what those things mean, how they are produced by archives, and consequently, what is forgotten. As part of the work, there was always the question of what is available to us, and how do we access it. At the same time, I was always asking myself what has been left out, what hasn’t been preserved, what can we no longer access, and what is the fate of those unknown glints of history. I found myself seeing that personal memory works much in the same way, following a similar dualism—what remains and what does not. The question then arose, what contributed to those things being relegated to oblivion: Was it a political choice? Some disaster that allowed for only part of the picture to be preserved? Or simply the passing of time, the decaying effect of it? These thoughts bled deeply into the work.

As well as this, I am fascinated by the question of where memory is located. We often presume it is within ourselves, but as Proust showed, it can be external to us too. I am interested in the “traceness” of objects such as old letters and photographs, particularly in the passage of time between their creation and my perceiving of them. I find the survival of the object and the human trace it bears miraculous.

KW: What was your thought process behind leaving the narrator unnamed?

IQ: One of the few ideas I had when I began writing Absence which made it all the way to the end was that it would be a novel about a narrator who drifts through other people’s stories and histories without revealing much about himself. I was interested in what I would call an apophatic characterisation of the narrator—revealing himself in what he reveals about others, not in what he directly reveals about himself. This idea came to me largely by sitting in pubs and cafes and listening to people’s stories. I realized that although many people speak about other people, they are often trying to hint toward something in themselves—in what they include and in what they omit. This straining of information about others can colour the person speaking as much as any central biographical detail. I decided that part of this anonymity had to include the narrator’s name in order for his facelessness, his obscurity, his spectrality to feel whole; without him, others could emerge.

KW: Did you think of each chapter as its own composition or short story? Or were they all deeply connected for the narrator?

IQ: The two novels that bore a large influence on Absence were Marcovaldo by Italo Calvino and Antwerp by Roberto Bolaño. For readers of these two novels, this might seem strange as aesthetically and narratively they bear very little significance to each other. But what they both allowed me to perceive clearly was two different kinds of novels constructed in parts. In Marcovaldo, Calvino uses the strict cycles of seasons to build his text. Whereas in Antwerp, Bolaño uses the poetic repetition of certain symbols and images to build up a looser kind of narrative.

For me, Absence sits somewhere between these two modes of constancy and fluidity. I see the stories as deeply connected and inextricable from each other, but the binding force of them is not simply a straight-line narrative, or a stringent external form. There is, of course, the Wilde poem which acts as the clearest thread, but then also certain images and motifs that repeat and stack together to establish a non-sensuous logic a la Bolaño.

Kyla D. Walker: Did you write Maggie; or, A Man and a Woman Walk Into a Bar with an outline or ending in mind? Or were the characters’ voices and anecdotes the guide?

Katie Yee: For some reason, the ending usually comes early in the process for me. That’s the only thing I know will happen. How we get there is up to the characters and their voices. When I’m writing, sound plays a big part in what comes next. The way a sentence sounds is often a greater consideration than the plot itself; language leads, and events echo back. I’m not an outliner. I wish I was that organized!

There were a few real-world considerations for my characters that helped create a vague timeline. Things like the normal number of days it takes for test results to come back and public school schedules for the kids. Having to hew to these time structures was helpful in keeping the plot moving, but it wasn’t something I was strict with myself about in early drafts.

Towards the end of this process, more in revision, I had to keep a Post-it timeline above my desk: APRIL, MAY, JUNE, JULY, AUGUST, SEPTEMBER with things like “School’s out!” and “Follow-up appointment” under each month. But that was more to make sure I got the time right and sent the kids back to school in September, that kind of thing. The Post-its I had were pretty weak, though, and never stuck to the wall for long. Time was always raining down on me as I was finishing the novel, which I thought was very poetic.

KW: Can you talk a bit about the names you used for the characters in the novel? Did these come immediately or did it take a while to land on the right ones?

KY: Names are so hard!! This is an observation that the narrator has in the book, when she’s struggling to name her kids. It’s a lot of responsibility, a lot of commitment. At first, I thought maybe no one except the tumor would have a name. There was a version where you only find out the husband’s name after they file for divorce, after she can no longer refer to him as “my husband.” Ultimately, that felt a little tedious and unspecific, at the line level, though.

I chose Sam for her husband because it’s a name I’m used to saying, a name I know how to get my mouth around. I have three very close friends that I call Sam—two Samantha’s and one Samaya—and I think I just felt comfortable with it, sonically. I also think it can be helpful to give even your “villains” bits of people you love, so that you as a writer might feel some subconscious tenderness towards them. To that end, Maggie I chose because I love Maggie Rogers, and I was listening to a lot of her music when writing this. I wanted to give her a name that sounded kind of benign, friendly even—which I’m told names that end in -ie do. (Hello, I’m Katie!)

The kids have the most special names to me. I’m pretty on the fence about having kids myself, but Noah and Lily are the two names I would have given my children. I love the sound of the name Noah, and something about the story of Noah’s Ark (pairing the end of the world and saving your family) felt right here. Lily was my grandmother’s name.

For all this consideration of names, though, you’ll notice I didn’t name the narrator. I’m optimistic that her voice gives her enough texture to grab onto. And I wanted you, reader, to feel like her character and her story could belong to you, too.

KW: What was your favorite part of the writing process for Maggie? How long did it take from start to finish?

KY: Writing the narrator’s best friend, Darlene, was so much fun. I’ve taken traits, habits, gestures, passions, and weird little anecdotes from all my best friends and put them into this character. She’s a love letter to each of them.

I worked on Maggie on and off for the past five years, since 2020. It was especially important to write Darlene during this time of social isolation because I wasn’t able to see a lot of my friends the way I was used to. Her reliability, her care, her hard questions and her tough love (when needed) were so essential, both to my narrator and to me. Writing this character and their conversations felt like hanging out with my friends again!

KW: What did revision look like?

KY: Before Maggie, I considered myself a short story writer; I had never stuck with a character for longer than 7,500 words. It was a challenge for me to write long. When I turned in my manuscript to my agent, it was barely 40,000 words. (A lot of my writing process was Googling “minimum words for a novel?” over and over again; the Internet seemed to think that 40,000 was on the cusp, but passable.) By the time I sold the book, Maggie was probably around 50,000 words. With both my agent and my editor, the vast majority of their notes read, “More here.” I loved that. It was like the scaffolding was there, and we just needed to build the rooms more solidly. It was so helpful to know which scenes to linger in a little longer.

Kyla D. Walker: Information Age is made up of many kinds of fragments (conversations with strangers and friends, pull quotes, narrated vignettes, texts, emails) that constellate and come together beautifully. How did you choose this structure, and how did each part ultimately intertwine to form the novel?

Cora Lewis: I think in many ways the structure chose me, in that it felt like a natural and intuitive way to organize notes and experiences from the reporting life. In the end, it made sense that the narrative should be mostly linear, temporally, but also that the fragments and vignettes should have an associative logic, so they’d accumulate meaning for a reader.

There were also writers I felt had given me permission to write this way and showed me how—Jenny Offill, Patricia Lockwood, Lydia Davis, and Amy Hempel. Annie Ernaux, Nancy Lemann with Lives of the Saints, Susan Minot, Renata Adler, Elizabeth Hardwick, and Grace Paley. Lauren Oyler even spoofs it in Fake Accounts. It was helpful for me to have all these models of the structure.

The form also feels suited to the times, in that it has a telegraphic quality—short bursts of information or snapshots—Instagram, texting, Slack, tweets. An experience of the infinite scroll. I tried to incorporate some Reddit comments, email excerpts, a quiz, headlines. My brilliant editor, Madeleine Crum, and Michelle Lyn King, the publisher of Joyland Editions, helped ensure the disparate parts came together to form a satisfying narrative arc, too.

KW: Did you write Information Age with an outline or ending in mind? Or was the narrator’s voice and the overheard dialogue your guide?

CL: I would say the narrator’s voice and overheard dialogue were the strongest guide. I wrote the book over a long period of time, and I ended up incorporating a number of events and developments, including Trump’s first election and the development of Large Language Models, but it was the narrator’s style of thinking and arrangement that carried the work. That was the through-line.

KW: How did the central setting and cityscape of New York help sculpt the plot and the prose?

CL: One of my favorite things about New York is how many varieties of encounter you have in a given day—on the subway, at a bodega, running or picnicking in a park or by the river, on the sidewalk, the ferry. Public libraries and museums and the shared fire escapes or roofs of apartment buildings. It’s intimate and public at once, which is not an original observation, but one that absolutely shaped the plot and prose of the book. It’s like the internet in that way. Another commons.

The protagonist of Information Age is also constantly leaving the city to go report on the rest of the country, or going to the Hudson Valley to spend time with family, and so there are these foils and contrasts to the city as well. Hopefully those juxtapositions bring out certain qualities of those different parts of the country—the urban versus the more rural or pastoral. And the narrator’s lack of experience with non-city life and people is also on the page.

KW: How did your past experience as a journalist inform or influence the story?

CL: My experience as a journalist taught me to always listen for the telling quote and the parts of an interview that are most affecting, interesting, or original. While I would be reporting, I’d have so many exchanges with sources that were evocative and interesting for reasons completely unrelated to the news report in question. I’d write those exchanges down and file them away, and many of them made it into the book. That practice was as valuable to me as learning how to produce clean, lucid copy efficiently—and learning how not to be precious with my writing. Journalism thickens your skin when it comes to receiving edits, and it teaches you to use fewer, better words whenever possible. Compression. Economy of language. That also shaped the book.

Reporting can also lead a person to treat everyone as a source. In Information Age, the narrator sees her friends and family as sources comparable to those she interviews for her articles. So she’s evaluating what they say—for trustworthiness, use, style. Same with strangers and the people she dates. There’s a democratic quality to her listening, maybe to a fault. Meanwhile, she’s trying to be a professional person, and have a love life, and be a good friend, and daughter. All during a hallucinatory, unreal election cycle.

Are journalists objective, cold-blooded conduits for relaying information? Maybe ideally they would be. Practically speaking, they’re people in bodies too…For now! And even the algorithms, AI, and ChatGPT—these reproduce human biases and distort the language they produce, their outputs, based on all the human inputs they’ve crunched and metabolized…Now I’m talking about the future of journalism. But some of that makes it into Information Age as well.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.