Our bounty of brilliant reviews this week includes Lauren Michele Jackson on Ron Chernow’s Mark Twain, Becca Rothfeld on Bridget Read’s Little Bosses Everywhere, Zadie Smith on Charlotte Beradt’s The Third Reich of Dreams, Arielle Isack on Sophie Kemp’s Paradise Logic, and Maggie Lange on Sophie Gilbert’s Girl on Girl.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s home for book reviews.

*

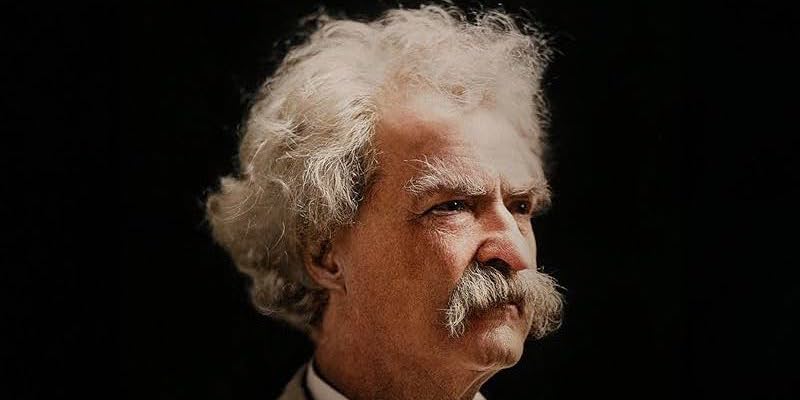

“Scholars of all stripes have catalogued, republished, fact-checked, and reconstructed Twain for more than a century. ‘Perhaps no other American author can boast such a richly documented record,’ Ron Chernow writes in Mark Twain, turning his distinguished attention to the subject in a mighty tome—some twelve hundred pages, with notes. No justification is needed for retracing a figure we never stopped talking about, although, for all its heft, this latest treatment adds little that’s substantively new. ‘Mark Twain’s foremost creation—his richest and most complex gift to posterity—may well have been his own inimitable personality, the largest literary personality that America has produced,’ Chernow writes. Fair enough. The boy drifted downstream; the man stayed behind, waving from the shore in impeccable linen.

…

“Knowing what he created from this enchantment, one may be tempted to credit Little Sam with a racial enlightenment, a notion that Twain disavowed. (‘In my schoolboy days I had no aversion to slavery,’ he recalled.) Chernow himself succumbs to the temptation. ‘Due to prolonged exposure to slavery at the Quarleses’ farm,’ he writes, ‘Twain had a fondness for Black people that didn’t stem from polite tolerance or enforced familiarity.’ That’s a misreading of Southern racial dynamics, where intimacy and domination were bound together like strands of rope. Twain, looking back with sharper eyes, acknowledged the unbridgeable distance: ‘We were comrades, and yet not comrades; color and condition interposed a subtle line which both parties were conscious of.’

…

“Chernow, ever scrupulous, does not ignore the complexities, but his caution becomes its own kind of evasion. Apologies accumulate like packing peanuts. Twain said some unfortunate things about Jews, but he also admired them. He didn’t always get race right, but he possessed ‘enormous goodwill toward the Black community.’ It is hard not to read such formulations—careful, cushioning, oddly managerial—as symptoms of a deeper unease.

…

“That creative arena—the one Twain opened up by writing a book that hasn’t finished becoming itself—is one of the few things in American culture that remain usefully unsettled. We’re not done with Jim because Twain wasn’t. Perhaps this is what we want from him still—not sanctity or scandal but a space of comic disorder where the rules of the novel, and the Republic, could be stretched, tested, and maybe gamed. If Twain belongs to anyone now, it’s the writers making mischief in the structures he left behind—not revering him but inhabiting him. He gave us a raft. It’s up to us where we take it.”

–Lauren Michele Jackson on Ron Chernow’s Mark Twain (The New Yorker)

“What are we buying when we purchase a product? Sometimes, the item itself, something as unglamorous and useful as laundry detergent or ink for the printer. But just as often, we are buying a fantasy—an assurance that we are a certain kind of person, a dream of a different kind of life. Companies that engage in multilevel marketing, or MLM, are especially deft at peddling this sort of intangible temptation. As the New York magazine journalist Bridget Read documents in her gripping and instructive new history, Little Bosses Everywhere: How the Pyramid Scheme Shaped America, they have to be, because they barely make a pretense of selling actual products.

…

It is easy to see why MLM is appealing to the bigwigs who profit from it, but what does it offer the low-level sellers who fall prey to its implausible promises? Little Bosses Everywhere is more about the scammers and their stratagems than it is about the scammed. Even by the end of the book, it remains somewhat difficult to fathom why so many people are taken in by what seems like such an obvious grift.

Nonetheless, the history Read recounts allows readers to infer how MLM might win over adherents. She sketches a vivid portrait of a cultish culture, replete with its own rituals and vocabulary.

…

“Perhaps above all, MLM allows participants to ‘refer to themselves as bosses’ and therefore to enjoy a central American currency: not actual money but the performance of entrepreneurial success. As one former FDA employee, reflecting on the agency’s attempts to regulate Nutrilite, once said, ‘Americans want to believe in tonics.’ In the absence of real medicines—real economic opportunities—placebos and miracle cures will always appeal.”

–Becca Rothfeld on Bridget Read’s Little Bosses Everywhere: How the Pyramid Scheme Shaped America (The Washington Post)

“The book had some modest success but never penetrated the American consciousness like the work of Arendt, perhaps because Beradt offers us not a complex hermeneutics of totalitarianism but rather a quite straightforward picture of the psychological effects of propaganda and manipulation upon a populace.

…

“Propaganda posters, megaphones, the radio: such devices appear in these dreams over and over. And such were the paltry propaganda tools Hitler turned to his advantage in spectacular fashion, though they were like crayons on paper compared with what a man like Elon Musk now has at his disposal. Usually, when people are making comparisons between now and then, they are thinking of the message and not the medium—that is, they think of Nazism itself, as a specific political ideology. The Third Reich of Dreams certainly provides many predictable parallels.

…

“There’s a bracing moment in The Third Reich of Dreams when Beradt reminds us that ‘the destruction of plurality’ as well as the feeling of ‘loneliness in public spaces’ was how Hannah Arendt characterized ‘the basic quality of totalitarian subjects.’ These are also fair descriptions of the effects of our present algorithmic existence. That of course does not mean that simply by disengaging from the algorithms we will make all our real-world problems disappear. Doing so will not solve climate change, end profound economic inequality, destroy racism and misogyny or bolster reproductive rights, end wars cultural and real, or magically transform the plight of migrants. But it might hasten the end of the misguided belief that self-selecting, yet algorithmically determined, online communities are any decent political substitute for geographic, localized, politically diverse, real-world communities. It might help to reinstate a less manipulated, more public, more shared place of debate, in which the possibility of actually knowing and at least partially comprehending your neighbor and their political leanings (rather than caricaturing and demonizing them) could re-emerge as a real political possibility. Which might in turn result in newly invigorated powers of concession, compromise, and consensus, all of which—whether you like it or not—happen to be vital for any healthy polis. That’s a whole lot of ‘mights.’ But in my dream, it’s worth a try, if only because it would so seriously hobble the most powerful and dangerous political lobbyists on the present scene: the tech bros. In my nightmares, Trump is only the Trojan horse. Musk is the real power. An unelected billionaire whose megaphone reaches every corner of the globe? O give us freedom of thought.”

–Zadie Smith on Charlotte Beradt’s The Third Reich of Dreams: The Nightmares of a Nation (The New York Review of Books)

“During the Holocaust, there was a word for a prisoner who was resigned to his death: a Muselmann. Primo Levi described Muselmänner in his memoir Survival in Auschwitz as ‘an anonymous mass’ that formed the ‘backbone of the camp.’ ‘[They are] non-men who march and labour in silence, the divine spark dead within them, already too empty to really suffer,’ he wrote. Muselmänner were men stripped entirely of any individuality or discernible identity; sheer deprivation debased them beyond the limits of recognizable humanity. In Remnants of Auschwitz, Giorgio Agamben calls this process ‘desubjectification,’ which rendered the Muselmann ‘the complete witness,’ a figure whose narrative presence could only function as testimony of the hideousness and abjection of the camps. All the Muselmänner ‘who finished in the gas chamber have the same story, or more exactly, have no story,’ wrote Levi. This isn’t for lack of trying. Since 2022, Sophie Kemp has published at least two stories about characters imprisoned in fictional concentration camps who readily acquiesce to their violent, horrific fates.

…

Kemp’s concentration camps literalize gender expectations as compulsory, inescapable structures in which people aren’t individuals but representatives of an ideal whose duties and desires are ordained by male authority figures. Her allegorical universes also contain a functional critique of labor relations—Hailey and the Adonises are tortured in the name of customer service—and there is some emotional realism in the uncanny, at times sexy, atmospheres of compulsion and coercion Kemp conjures for her Muselmänner. Indeed, desire and exploitation do shade imperceptibly into one another under patriarchy, or when you have to have a job. You get what she means. Paradise Logic, her debut novel, is set mostly in Gowanus, yet it dares to ask: Can a twenty-three-year-old girl who lives in Brooklyn also be a Muselmann?

…

“This collision of the epic and the mundane scans initially as farcical, but it is also an explicit injunction to take Reality seriously as a vessel through which something startling and true about the condition of womanhood will express itself. Kemp guides us to find her novel’s insights not in what Reality herself thinks, but in what happens to her as a hapless individual completely subject to forces greater than herself—forces that we can’t expect her to comprehend. The novel’s insights, in other words, lie in Reality’s desubjectification; she is a Muselmann par excellence, the latest representative, to hearken back to Levi, of that ‘continually renewed and always identical’ organism whose witness might allow us some insight into our shared universal condition.”

–Arielle Isack on Sophie Kemp’s Paradise Logic (The Baffler)

“Girl on Girl covers how American culture writ large treated women from the 1990s to the 2010s. It’s to Gilbert’s credit that she makes a cohesive history emerge from this morass of references—from Kids to The Hangover, Heidi Montag to Marie Calloway, Bridget Jones to Cindy Sherman—that arise out of this era. A Pulitzer Prize-nominated critic and staff writer at the Atlantic, she draws examples from the tenor of blog coverage, bro buddy comedies, postfeminist auteurs and the detractors who obsessed over women over these decades. Throughout, her organization is as confident and nimble as her arguments. The more visible the woman, Gilbert argues, the more the culture resented the woman for making them look

…

“What differentiates Gilbert from the recent reappraisals of the turn-of-the-21st-century misogyny is her objective. She’s less interested in the motivation of the photographers or movie directors or magazine editors than she is in the mechanics of power. Despite her uptake of figures such as Simpson, she’s not calling on us to apologetically reevaluate mistreated idols. She’s focused instead on the way treatment of such figures (and many more women besides) infected people.

…

“Gilbert knows the impossibility of reporting on the temperature of the water you’re in; she opens her book with Adrienne Rich’s statement: ‘Until we can understand the assumptions in which we are drenched we cannot know ourselves.’ But in focusing on the recent past, she aims to provide us with a critical lens to assess our current moment. Gilbert is a critic skilled in the art of seeing close-up and faraway all at once, a Vertigo effect of cultural observation. Girl on Girl doesn’t settle into outrage or pity, but instead offers a clear-eyed, unblinking stare that conveys one thing: I see what you’re doing.”

–Maggie Lange on Sophie Gilbert’s Girl on Girl: How Pop Culture Turned a Generation of Women Against Themselves (The Washington Post)