Four in ten U.S. adults believe humanity is “living in the end times.” We see existential threats in the form of climate change, our political campaigns, war, and AI. Correspondingly, the apocalypse is an obsession in our literature. Common are post-apocalyptic books, which take for granted the end of the world as we know it and explore how we’ll fare in the aftermath. Somewhat less explored is the pre-apocalyptic moment—the moment we see ourselves in now. What do we make of the dread, doom, and occasional excitement of living in anticipation of catastrophe?

In my novel, Circular Motion, the Earth starts spinning faster and faster. As days on Earth quicken from twenty-four hours to twenty-three, then twenty and below—the sun rising and setting ever more frequently—violent storms and economic meltdowns portend a civilizational collapse. Maybe the world will end… or maybe humanity will adapt. The characters must learn to live in this uncertain time of looming threat.

The crises of today may or may not lead to annihilation. What’s certain is that our lives will continue to be shaped by annihilation’s possibility. Each of these eight pre-apocalyptic books is set in the run-up to a particular apocalypse that only arrives near the end of the book, if ever. Most are not stories of mass destruction; rather, they are stories of life set to the soundtrack of alarm bells.

Apocalypse: Asteroid

The Last Policeman by Ben H. Winters

In six months, an asteroid will wipe out most life on Earth. People are abandoning their jobs, turning religious, experimenting with drugs, hanging themselves. Trying to keep his head amidst economic and spiritual mayhem, a young detective commits himself to solving a local murder case before the world ends. A more mature author might have smoothed down The Last Policeman into a pat meditation on the value of life, a reconciliation between the tragedy of a single death and the statistics of mass extinction. Winters, however, plays to baser tastes, thank god. Against his existential backdrop, he gives us a bloody (arguably, even, fascistic) cop novel, which doesn’t pretend that life is better understood when backlit by death, but perhaps that mortality intensifies our perspectives on life, misguided as they may be.

Apocalypse: Alien invasion

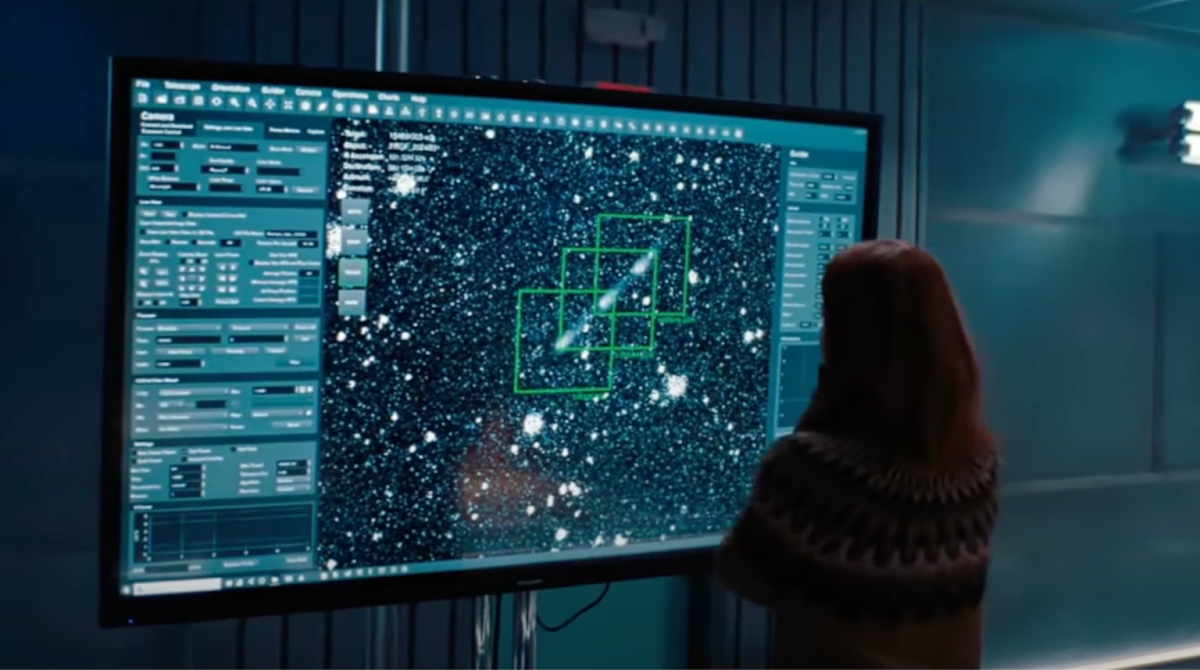

The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu

The Trisolarians are coming! As news spreads about the approach of an alien fleet, political factions debate whether to cooperate or prepare for war. The Three-Body Problem captures humanity’s ambivalence toward being supplanted. Annihilation is a fearsome prospect, but it throws into relief the inadequacies of the civilization that we have. We’re first introduced to the working of human politics through a brutal struggle session during the Chinese Cultural Revolution, and as the novel proceeds, terrestrial society gets arguably more dysfunctional. All clocks are counting down to our deliverance/destruction.

Apocalypse: Climate crisis

The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson

Some earlier works of climate fiction by Kim Stanley Robinson depicted Earth in the post-apocalyptic distant future, flooded out or ravaged by mass extinction. The Ministry for the Future, in contrast, shows Earth as it is—or at least could be—today: imperiled by climate change and responding to that threat. Through bureaucracy, diplomacy, and direct action campaigns, Robinson’s characters address the looming prospect of climate apocalypse. Here is the most dismally realistic book on this list, and also the most hopeful.

Apocalypse: Polycrisis

The Old Drift by Namwali Serpell

Five generations in Zambia, from the turn of the twentieth century to the near future: The course of history in this novel zigs and zags, but an ever-present dread makes it clear that whatever direction we’re heading, it’s not good. As colonialism gives way to globalization, then consumerism and techno-autocracy, politically engaged characters come to see polycrises mounting everywhere they look. Will their way of life be undone by surveillance devices implanted in their hands? By swarms of tiny drones? By predatory foreign lending or climate change? In rallies, they read from the Book of Revelation. They cry that the “end of days is here!” Ultimately, it’s their very fear of annihilation that causes the flood.

Apocalypse: Nuclear proliferation

When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamín Labatut

Ostensibly fiction, most of this novel about Erwin Schrödinger, Werner Heisenberg, and others is true. That’s to say, it is a record of these men going about the business of developing the instruments of apocalypse: poisonous chemicals and nuclear bombs. What’s fabricated is the men’s dreams, their longings and their madness. In one of Heisenberg’s prescient nightmares, he imagines the future victims of the atom bomb; yet he continues to expand the possibilities for humanity’s annihilation. Apocalypse, here, is a temptation: it is the desire to finally grasp the world, if only by obliterating it.

Nuclear War: A Scenario by Annie Jacobsen

Here’s a weird one. Ostensibly nonfiction, there are no dreams, just actions and reactions. Beginning with a hypothetical nuclear strike on the Pentagon, Jacobsen imagines the ramp-up of an all-out nuclear war, providing estimates of the death toll as it rises with each passing minute. The lead-up to this apocalypse is short. As a former commander of the US Strategic Command is quoted as saying, “The world could end in the next couple of hours.”

Apocalypse: Colonialism

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe

This is, to my mind, the canonical pre-apocalyptic novel. Achebe brings to life a civilization in all its grandeur and complexity, only for it to be destroyed by the arrival of white colonizers. Things Fall Apart introduces the questions that will later be asked by alien apocalypse novels (Should we collude with the aliens or resist?), nuclear apocalypse novels (What constitutes technology progress?), and climate apocalypse novels (Who’s in charge here?). Even asteroid novels: As if the white missionaries are stony, incomprehensible projectiles of impending death, Achebe searches for the meaning of life in a world that is doomed. The doom, in this historical case, is all too real.

Apocalypse: 9/11

“The Suffering Channel” from Oblivion by David Foster Wallace

A bonus entry. Something smaller than an apocalypse novel—really it’s a disaster novella—”The Suffering Channel” follows the employees of a fictional lifestyle magazine, whose office is on the sixteenth floor of 1 World Trade Center, as they compose the magazine’s forthcoming issue, set to publish on September 10, 2001. The storylines, like many of Wallace’s best, get tangled in the weeds of the characters’ quotidian concerns—their workplace politics, their sartorial insecurities—and the result is something transcendent. Here, the impending doom of 9/11 freights every gesture, every gaze met and missed. Mundanity becomes profound, even beautiful, but painful too. This is not a simple story about appreciating life while you have it. The tragedy of destruction doesn’t negate the sorrow of existence; the sorrow of existence doesn’t lessen the tragedy of destruction.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.