If we count the three bears into whose lives Goldilocks intruded and Winnie-the-Pooh, then Paddington Bear is the fifth of the species who, crossing the Atlantic from Britain to America, provided the basis for more than ample cultural productions of immense popularity in which bears are central.

Article continues after advertisement

Paddington is an Andean or spectacled bear from “darkest Peru” found abandoned by an English family in London’s Paddington Station, dressed in his now familiar squashed hat, holding an empty jar of marmalade, and with a tag hanging around his neck saying, “Please Look After This Bear, Thank You.” The man behind this bear (A.A. Milne’s successor) was Michael Bond. Born in 1926, conveniently for me the year Milne published his first Winnie-the-Pooh book, Bond left school at age fourteen even though his parents hoped he would go to university. He started working at the BBC when he was fifteen years old, employment interrupted during World War II so he could serve in the military.

Around the war’s end, he resumed working at the BBC, eventually as a cameraman, and began to write short stories and plays. He published A Bear Called Paddington in 1958. He had not intended to write for children, and it “started life as a doodle,” he later recalled. “I was looking around the room and we had this small bear, which” he had purchased at a shop near Paddington and then “had been a kind of stocking filler for my first wife, and I wondered, idly, what it would be like if it was a real bear that landed on Paddington station and I typed the first words down.”

Well over one hundred books featuring Paddington eventually appeared, with five more in the series in print between 1959 and 1964 while Bond continued working at BBC. They were so successful that he could quit his BBC job to devote himself full-time to writing.

The dust jacket of A Bear Called Paddington describes him as “an earnest, gentle, and well-meaning bear” with “an absolute talent for getting into trouble” despite his good intentions. Inside, Bond introduces us to Paddington, a stowaway who has emigrated from Peru. (Bond originally described Paddington as having come from “darkest Africa” but switched to Peru when his literary agent told him there were no bears in Africa.) Paddington used to live in Lima with his Aunt Lucy, who taught him to speak English because she wanted him to emigrate. He had to do so because she knew that eventually she would have to enter a home for retired bears. At the London railroad station, the bear eagerly accepts the offer of Mr. and Mrs. Brown to come and stay in their house, something they know their children Judy and Jonathan will enjoy. The bear announces that he has a Peruvian name no one could possibly understand, so the Browns name him after the railroad station where they found him.

Bond and social justice advocates used Paddington to represent sympathy for refugees, immigrants, and asylum seekers, with Paddington’s Aunt Lucy insisting, “London will not have forgotten how to treat a stranger.”

Polite and well mannered, Paddington speaks proper English. Yet ironically, chapters tell stories of how he continually gets into trouble when he tries to right what he sees as a moral wrong because the rules and customs of his new world are so unfamiliar. When necessary or when he cares to use it, he has “a very powerful stare” that “he kept for special occasions.” Otherwise, he is preternaturally well meaning and kind. Nonetheless, he frequently causes chaos—at the Underground, the department store, the theater, and the seaside. Yet if Paddington is troublesome, it is not because he is a large and wild animal but a small and civilized one who makes mistakes because of innocence and not malice. Indeed, at key moments the mishaps he causes end up benefiting those in his host society.

This happens, for example, when he stumbles into the window of a department store and brings it additional business; when he turns Mr. Brown’s canvas into a prize-winning painting; or when he unintentionally wins accolades as an actor.

Paddington, an observer remarked in 2014, three years before Bond’s death, represented “an extraordinary level of success for a British children’s book character who doesn’t play quidditch—one matched only perhaps by that other endearingly bumbling bear, Pooh.” And as was true with Winnie-the-Pooh, Paddington became a celebrity, with a capacious and long-standing franchise. As with other bear characters, the brand was licensed to a series of corporations around the world, including as a book translated into forty languages and selling more than thirty million copies—to say nothing of theater productions, postage stamps, cartoon strips, a cookbook, feature-length films on the big screen and television sets, and special shops with merchandise for Paddington and friends. Paddington’s Guide to London would take you to a statue of the bear himself in Leicester Square. And of course there were stuffed animals galore. Three months before she died, Queen Elizabeth II had tea with Paddington as part of the way the palace promoted her jubilee.

Race and gender are prominent when it comes to thinking of other children’s books that feature bears. With Paddington those could be appropriate categories, but immigration is uniquely relevant to Bond’s creation. Attending school in Redding in his early teens, Bond had seen children at the train station, evacuees from London who, he recalled, “all had their labels round their necks with their names and addresses on them and a little case or package containing all their treasured possessions. So Paddington, in a sense, was a refugee.”

Also inspiring him was knowledge of the Jewish refugees on the Kindertransport, beginning in late 1938, as well as mid-1950s refugees from Hungary. Paddington’s dear friend Mr. Gruber was an antiques dealer and Hungarian refugee. Bond based Gruber on Harvey Unna, his first literary agent, someone who had left Hamburg to escape the grip of the Nazis. Gruber, Bond later remarked, was “a lovely man, a German Jew, who was in line to be the youngest judge in Germany when he was warned his name was on a list. So, he got out and came to England with just a suitcase and £25 to his name.”

In the late 1950s, before restrictive policies took hold with the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act, as many as 100,000 immigrants arrived in Great Britain annually, mostly from the West Indies, Africa, and Pakistan. In 1958, a few weeks before Bond’s first Paddington book appeared, racist anti-immigrant youths using the slogan “Keep Britain White” attacked West Indian residents in Notting Hill, less than two miles from Paddington Station and where Bond lived. Many who supported immigrants who came to England during and after World War II deployed Paddington as a symbol in the fight for their acceptance. Bond and social justice advocates used Paddington to represent sympathy for refugees, immigrants, and asylum seekers, with Paddington’s Aunt Lucy insisting, “London will not have forgotten how to treat a stranger.”

Inevitably scholars saw issues in more complicated ways, arguing as they did about whether Bond’s stories amplified imperialism, complicated issues such as identity and foreignness, and challenged racism. The scholar Philip Smith shows how Paddington films released in the second decade of the twenty-first century provided Brits with a sympathetically multicultural narrative that stood in opposition to anti-immigrant discourse. This was because Bond’s stories depict Paddington as a bear who presents no threat to Britain’s social and cultural orders.

After all, although physically he is marked as non-white, Paddington dresses, acts, and speaks in ways marking him as truly English. “Paddington reads as ‘ours,’” Smith observes, “because he is an immigrant whose manners and outlook express, and upon whom audiences can project, qualities of Englishness.” In addition, he notes with both the early books and later films in mind that “English cultural praxis can tolerate difference in terms of race but demands homogeneity in language, habits, mannerisms, taste, and beliefs.”

Looking at A Bear Called Paddington with conditions that obtained more than half a century after its publication, Kyle Grayson recently offered a more complicated assessment. Bond’s first Paddington book, he asserts, “is both complicit in and critical of contemporary understandings of foreignness, liberalism and migrants.” In some instances, the emphasis is on how his “hygiene, poverty and education” mark him as a problematic immigrant and foreigner. In contrast, the portrayal of Paddington reassures natives of England about the meaning of being “a good host and a good foreigner in a liberal society.”

If Paddington and those who welcomed him came to epitomize one aspect of Britishness, perhaps the most quintessential of American cartoon bears are the Berenstain Bears. The more than three hundred books about the Berenstain Bears printed in more than 260 million copies since 1962 provide an important marker in the history of children’s books that feature bears.Though there had been many published on this side of the Atlantic Ocean before, there was no American blockbuster precedent. Teddy bears were already everywhere but not part of a franchised empire that emerged from a book. Yogi Bear debuted in 1958 but on-screen, not in print. Given that Goldilocks and the Three Bears, Winnie-the-Pooh, and Paddington originated in Great Britain, the Berenstain imprints were the first homegrown American books for children whose franchise achieved such heft.

__________________________________

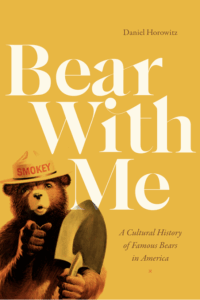

From Bear With Me: A Cultural History of Famous Bears in America by Daniel Horowitz. Copyright Duke University Press, 2025.