May 8, 2025, 3:24pm

Louis C.K., the disgraced comedian, has written a novel called Ingram, set to come out in the fall. If you need a refresher on C.K., Megh Wright’s excellent piece from 2018 lays out the sexual harassment accusations, and why C.K.’s return to comedy was a sad inevitability with bigger stakes than one man’s redemption arc. And more recently, Seth Simons wrote about why MeToo mattered, especially for a comedy industry that has aggressively learned the wrong lessons after discovering predators in their midst.

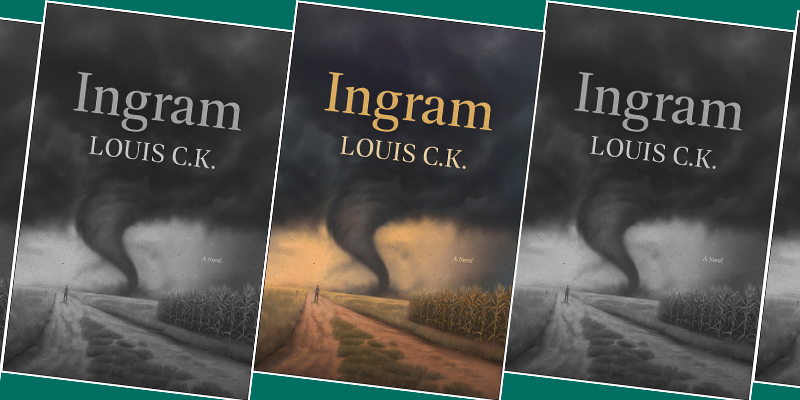

In the years since, C.K.’s gone right back to performing and releasing specials, and now we’ve learned that he’s also written and sold a novel. On his Instagram, C.K. described the book as “a literary fiction novel. It’s a very dramatic story. And I better confess to you this book is not particularly funny.” All to say, it’s a departure from his previous stuff.

So what is the novel about? It’s kind of hard to tell at this point, especially based on what’s available right now. Marketing descriptions for books tend to be vague, and especially for literary novels that don’t lend themselves to simple synopses. But I was struck by just how vague this one is. Let’s take a look.

A suspenseful, often harrowing yet hopeful odyssey through rural America follows a young drifter’s coming of age in an indifferent world, in this debut novel by comedian Louis C.K.

Okay, not a bad log line at the jump. A little gestural, but it sounds exciting at least. “Suspenseful,” “harrowing,” “hopeful,” and “odyssey” is piling on a lot, but maybe pointing to something action-packed and adventurous. Could this be flirting with genre fiction?

But a young drifter in rural America set against an indifferent world gives me a little bit of pause, insofar as it feels too close to a GOP SuperPAC ad about how “real America is being left behind.” But it’s also, to be fair, a way you might describe Grapes of Wrath, so if C.K.’s secretly been able to write like Steinbeck this whole time, I guess this description could break either way.

When Ingram is forced by overwhelming poverty and spiritual exhaustion to walk away from his home, he leaves behind a neglectful childhood on a dirt farm on a dead-end road.

We’re not getting a ton more specific here: a farm and a bad, poor childhood is something, but still pretty broad.

We’ve at least got a name for the character. And Ingram isn’t a common name, so maybe we’re meant to read something into that. I know that the guy who killed Christopher Marlowe was an Ingram—Is there something about how a spiritually exhausting America is killing the author and/or live theater?

This second sentence is dashing my hopes that this book might have some fun genre elements, though.

With no family, no resources, and no practical understanding of the world, Ingram’s only compass is the daily fight to survive and the narrow dream of one day owning a truck.

A little repetitive: Ingram’s bad situation is getting worse, and troubles are piling up for our young drifter. And if that wasn’t enough, he also has no practical idea of what’s going on. This is maybe set before the internet would have allowed Ingram to access a wealth of how-to YouTube videos.

We are getting one good detail: Ingram wants to own a truck someday, which is a very specific motivation. Other than the name, it’s maybe the most specific detail in this entire description. Still reading like a political ad though: “Real Americans just want a truck and relief from their spiritual exhaustion.”

A picaresque novel set against the backdrop of working-class Texas, Ingram invites readers to see the world through the eyes of a child who drifts through a tough American landscape of corn farms and oil fields, guided by diner waitresses, migrant workers, and criminals, trying to make sense of a world that doesn’t care about him anymore than a jungle or desert does for the creatures that toil to survive within them.

Amongst the lists of American things, we find out that this book is set in Texas. Or I guess the “backdrop” is Texas, which might encompass neighboring states. Would you say that the southern part of Oklahoma has Texas as a backdrop?

We learn that Ingram is a child and that he’s meeting a lot of stock characters. And this world is so tough that it’s simultaneously both a jungle and a desert, some kind of super biome that is less caring than either would be on their own.

I’m resisting the urge to psychoanalyze, but I’ll just say that we’re four sentences in and we’ve already heard a lot about how the world is cruelly set against our hero. “Picaresque” is a bit of a red flag, too, in that I’ve always understood the form to be a way to satirize society and its faults through the eyes of a clever rascal, who is also typically immoral or a criminal. A bit too close to home.

The reality Ingram discovers is wild and cruel, but filled with unexpected wonders. Though this young boy faces tornadoes, explosions, thieves, and rampant violence, his curiosity, humor, and resilience never dull.

We’re treated to a little crack of sunshine with “unexpected wonders” before being bludgeoned with another list of horrors. “Tornadoes, explosions, thieves, and rampant violence” is an impressive list, in that it gets more vague as it goes on: we start with a specific kind of storm and end on the nonspecific idea of the unchecked spread of brutality.

As he begins to push against the tide of social and natural bad luck that seems to almost chase him, Ingram begins to forge himself into an individual with agency and the ability and right to choose his own moves, even if he’s not always prepared for the consequences.

Okay, we’re getting some character agency here! Ingram is pushing, forging, and choosing. It’s hard to avoid putting this sentence on the therapy couch too, what with the “tide of social…bad luck that seems to almost chase him” and the rediscovery of “agency” and the “right to choose his own moves.”

Has he gotten that truck yet?

Through Ingram’s journey, he begins to come to terms with a forgotten tragedy from his past that shapes the way he understands himself, his family, and his own place in the world.

A late-breaking “forgotten tragedy”: so there’s a trauma plot also. Interesting, perhaps, but it’s just another vague thing we don’t know a lot about.

Thinking about what this book could be, I’m reminded of Matt Zoller Seitz’s recent review of the movie Rust, and his line that “it’s tough to assess this film’s virtues and defects without the real-life tragedy intruding.” When the description of Ingram is so vague, it’s hard to avoid filling in the blanks with real life details and guessed-at motivations. Is C.K. just writing a road novel about America? Or is the book about a funny and resilient character, who rises from the dirt only to find a world set against him and his humble dream of truck ownership, about something else?