In the window seat in economy class, I turn my face to the glass so the woman next to me can pretend she doesn’t notice that I’m crying. She’s sitting between me and her teenage daughter, who is plugged into her gaming device. Right now I wish I had one too. I wish I had a mother. I pull down my facemask, slow my breath and count to ten. The flight, from New York to Tokyo, is twelve hours.

Article continues after advertisement

When my mother was dying in New York, in December 2020, the city was in its eighth month of lockdown with no vaccines. The hospital waiting room where I’d taken my own children for stitches and reassurance was now a row of taped-off chairs. I walked out of the sliding doors and circled the long hospital block like a sheepdog. My mother was a poet, Jean Valentine. Or maybe she was the poet, Jean Valentine, who also happened to be my mother. She mothered words, not children. My mother was secretly, fiercely ambitious. A complicated secret for women of her generation. When she was a clinically depressed young mother with two daughters, she won the 1965 Yale Series of Younger Poets award. After she died, we found her statue for the National Book Award in the hall closet under a pile of shoes. When one of her poems was selected for the “Poetry in Motion” series on the subway, she let me frame a poster from the MTA and put it up in the hallway.

“My Words to You”

My words to you are stitches in a scarf

I don’t want to finish

maybe it will come to be a blanket

to hold you here

Love not gone anywhere

One morning, I saw she’d stuck a Post-It note over the line: “to hold you here.” She had changed one word: “to warm you here.” When I asked her about it, she smiled and said, “It’s better, don’t you think?” She would have broken the glass to change that word.

On the subway, I always tried to get a seat underneath her poem. The last line made me laugh: Love not gone anywhere. My mother disappeared all the time. Even when she was home, she was gone. I was the kid on the floor at her poetry readings; doing homework under the kitchen table where she sat with a pad of paper, unable to perform anything resembling motherhood. If I tried to look over her shoulder, she covered the words with her hand.

In my teens, I was better at pretending to be brave than I am now, but my mother saw through me more than I thought.

I was out the door at fifteen, telling myself I didn’t need a mother. If I had to ask her something, I would call around to her friends and try to find out which artist residency she had gone to. Yaddo? MacDowell? There was an office number where I could leave a message if it was urgent. At that age, it was hard to figure out what was urgent—everything? Nothing? Most of the time I decided not to call. Adept at becoming part of other families, I spent most nights in the Village with three dark-haired sisters whose mother sat enthroned on a worn couch in the living room. Homemade bookcases went from floor to ceiling, with albums across the bottom row. A faded Jean Seberg holding a glass of whiskey and a hand-rolled cigarette, she taught me about jazz. In the 1970s everything was different below 14th street. The uptown school where I was on scholarship blinked out in the flickering light of Downtown.

I bounced through a series of high schools and fell in love with a girl as lost and overeducated as myself. We met on the first day at a last-ditch school. Three weeks later we emptied our lockers and went downtown to get our palms read. We “ran away” to her grandmother’s empty summer house and enrolled ourselves in the local high school. At the end of that year, she went to college and I told my parents I was going to the University of the World. A good exit line that got me as far as a job in a sandwich shop near Harvard Square. My father, whom my mother married and divorced twice, failed to convince me to attend the only college that accepted me. My mother gave me a copy of The Narrow Road to the Deep North by Matsuo Basho.

I took it with me everywhere, shoved into my backpack, a slim seventeenth-century book of Haiku poetry popular in the 1970s. Basho resonated with the era’s romantic idealism: finding yourself on the road, rejecting society, and embracing nature with a strand of Buddhism. Born too late for Haight Ashbury, I worshipped my long-haired older cousins who added Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and On the Road to my backpack.

In my teens, I was better at pretending to be brave than I am now, but my mother saw through me more than I thought.

“Beka, 14”

Squat, slant-eyed, speaking in phrase-book phrases, the messenger

says he is your brother, and settles down on his heels

to wait, muffled in flat, supple skin, rope over his shoulder. You

wait, play, turn, forget. Years,

years. The messenger is both like the penguin

who sits on a nest of pebbles, and the one

who brings home the pebbles to the nest’s edge in his beak,

one at a time, and also like the one

who is lying there, warm, who is going to break out soon:

becoming yourself: the messenger is growing

strong, tough feet for land,

and strong wings for the water, and long

butter-yellow feather eyebrows, for looks. And will speak,

calmly, words you already know: “thread,” “island,”

“must”: now, slowly, just while you lie on your cot there, half-

dozing, not reading, watching the trees,

a summer, and a summer; writing long pages, tearing them up;

lying there under the close August window, while at your back

the water-lit, dotted lines of home start coloring in.

My mother was unresponsive as I read to her in the hospital. I was given two hours to visit each day, from 4:00 to 6:00 pm. She didn’t have COVID; if she had I wouldn’t have been allowed on the ward at all. It was Christmas, and a Lucite shield reflected the colored lights from a miniature tree at the nurses’ station. Rushing to get there in time, I had grabbed poets from her bookshelf. Dickinson, Bishop, and, at the last minute, The Narrow Road to the Deep North. The pages of her copy of Basho were soft with age. I still knew the opening lines by heart.

The moon and the sun are eternal travelers. Even the years wander on.

A lifetime adrift in a boat, or in old age leading a tired horse into the years,

every day is a journey, and the journey itself is home.

I stopped reading and looked at her transparent oxygen tube. I had grabbed exactly the right book: she was on her own narrow road. I glanced out the window at the metallic winter sky and decided that when all this was over I would go to Japan and follow in Basho’s footsteps.

To look for her? To bring her with me? I still don’t know. She didn’t always want my company, but I was hers and she was mine.

When I got home to Brooklyn, I climbed into bed and kept reading Basho, dreaming of Japan.

The second year of Genroku, I think of the long way leading into the Northern Interior under Go stone skies. My hair may turn white as frost before I return from these fabled places—or maybe I won’t return at all.

Six months later, I locked her apartment door for the last time. I felt nothing but relief. I applied for a research grant from my university for a walking tour of Basho’s narrow road, then changed jobs, left the funding behind, and went to Japan.

*

The plane is making its long slow arc over the Pacific when the woman next to me taps my shoulder and motions for me to push up the window shade. The dark horizon is a blur of red, orange, green, and white. The northern lights. My seatmate nods, smiling, even her daughter looks up from her iPad. I press my forehead against the glass, cupping both hands around my eyes to block out everything but the light at the bottom of the sky.

The airport is all I will see of Tokyo. The public bathrooms have bidets in every stall and the airport is spotless and quiet at 5:00 AM. I stumble into a sake bar at the food court thinking I can order a cup of tea and the egg on rice glistening on a laminated menu. I cannot. Someone comes out from the kitchen to explain to me in English that this is a sake bar, you have to drink sake, not tea.

I repeat my two words of Japanese: Hi. Origato.

At the Tokyo train station, I look for a train leaving for Sendai, the city where my tour begins. On the platform, everyone stands in numbered rows, well dressed, calmly plugged into their earbuds. I follow the other passengers onto a train that carries me north in high-speed dream time. Speaking, eating, and drinking on public transportation is discouraged in Japan, and the train car is as quiet as a study hall. Sendai is the closest city to Fukushima, site of the 2011 tsunami and nuclear disaster. The Great East Japan Earthquake was a six-minute event that killed nearly 20,000 people and shifted the earth on its axis. Fukushima remains largely uninhabitable, but Sendai station gleams, a transportation hub extending into a mall filled with shops and restaurants.

When Basho came to Sendai in 1689 with his companion Sora, a poet and student, they had already been walking for five weeks from Edo (Tokyo).

Crossing the River Natori, I entered the city of Sendai on May the fourth, the day we customarily throw fresh leaves of iris on the roof and pray for good health.

There are no green leaves on the roofs of Sendai in 2023. My hotel is set inside a nondescript office building opposite the station. The clerk hands me a welcome packet from the walking tour: a spiral-bound booklet with photographs and detailed walking directions. I take the elevator up to my room and toss the guidebook on the desk. I am terrible at following directions. I want to lie down on the stiff hotel sheets and skip dinner altogether but force myself to stay awake and fight jet lag. I walk into the rainy afternoon. On a bridge above the railroad tracks, a mother and daughter walk slowly toward me. The mother carries a plastic bag and a clear umbrella. The child doesn’t look at me.

When I was her age I was proud of having my own house key. Nobody else my age had one. But I froze before turning the lock to our apartment. Was anyone home? The mother of laughter and friends over for coffee? The mother of the bedroom door closed and shades drawn? I closed my eyes and smelled the smoke from Mom’s cigarette curling above the kitchen table, turning my key when I heard women’s voices. Mom and Jane Cooper, a poet friend, were sitting at the table with all the signs of life: coffee, cigarettes, typewriter paper.

Jane turned toward me with her buck-toothed smile and I leaned against my mother, handing her an art project my teacher said was too small for a flower vase. Buttercups would fit in this little pot. Whenever I found a buttercup in the park, I ran to my mother, who held it under my chin saying, you love butter! Mom pushed aside some papers to place my vase in the center of the kitchen table. I pretended to do homework while Mom and Jane read their poetry aloud, pens scratching on paper. How could I get Jane to stay forever? When she left, Mom took her cigarettes into the bedroom and I heated up a can of SpaghettiO’s, eating close to the television with the volume down low. My favorite shows were survival adventures: Lost in Space and Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea. Later, I walked on tiptoe to the edge of her bed. My mother was sleeping with all her clothes on, pills and cigarettes on the bedside table. I watched the rise and fall of her narrow chest for a long time. Just making sure.

On one of his journeys before he took the northern road, Basho came across a child left alone on a river bank.

On the bank of the Fuji River, we came upon an abandoned child, about age two, its sobs stirring our pity. The child’s parents must have been crushed by the waves of this floating world to have left him here beside the rushing river to pass like dew. I thought the harsh autumn winds would surely scatter the bush clover blossoms in the night or wither them—and him—in the frosty dew of dawn. I left him what food I could.

Hearing the monkey’s cries—

what of the child abandoned

to the autumn wind?

How can this happen? Did his father despise him? Did his mother neglect him? I think not. This must be the will of heaven. We mourn his fate.

Basho leaves the boy behind. His solitary work comes first. The gods will protect you, it’s the will of heaven, and the child by the river will pass like dew.

I want the poetry but I am bone-tired of that story.

*

Twelve hours ahead of New York, I call my elder daughter and tell her that Japan in the twenty-first century has absolutely no relationship to Basho in the seventeenth century. How could I not have thought of this before? She laughs at my jokes and tells me it will all look better in the morning. I hold my phone over the guide book to show her tomorrow’s walking directions. There are red arrows drawn on photos of chain link fences and drab village streets, warning me not to go left at the soccer field, but bear right across the highway.

I was afraid of her response to the thread of suicide running through my novels. We never discussed it.

“You know, Mom, it looks kind of treasure-mappy.”

I wake at 2:30 am and when I give up sleeping, I work on an assignment that’s due as soon as I get back. By the time the sky turns white through the hotel window, I’m in a much better mood. I eat in the downstairs restaurant where the tea is green and the coffee is weak, but it turns out I love miso soup for breakfast. When I leave my luggage at the desk for the touring company, I don’t see any other suitcases. There were two options for this tour, guided and self-guided. I chose self-guided because it was cheaper and I wanted to be alone for this journey. I’m also a snob, too proud for tour groups. I hoist my backpack onto my lonely middle-aged shoulders and take a local train to a suburban station. When Basho and Sora left Sendai, their host, a painter, gave each of them a pair of straw sandals with indigo laces.

It looks as if

Iris flowers had bloomed

On my feet—

Sandals laced in blue.

Holding my treasure map, I walk carefully down the stairs, along the chain link fence, and past the soccer field, then bear right across the highway. White tents with purple flags ripple below the hill—iris plots as big as rice paddies. The flowers stand with their mouths wide open, blue, white, yellow, and purple. Elders sit on benches or in wheelchairs pushed by younger relatives or caregivers. Everyone is smiling.

*

Shiogama Shrine has a stairway of 202 steps guarded by a pair of stone komainu, or “lion-dogs” placed on opposite sides. Standing between them with my aluminum trekking poles, I think of Basho, an old man leaning on his staff, in this same current between the lion-dogs. Basho died at fifty, younger than I am now. Will I live long enough to consider myself an old woman? Did my mother ever think of herself as old? She was one of the least vain people I know, leaving behind only half a closet of clothes. Her bureau drawers held scraps of paper, postcards from friends, and light scarves that slipped through my fingers.

Brightly painted vermillion poles support the temple over gods of thunder, lightning, and the sea, who taught the locals how to make salt from the ocean. I stop at a stone ox with a gentle expression lying beneath a thatched hut. The sign says that rubbing the ox brings good luck, its forehead dark with the sweat of human longing. Instead of a stone, my mother asked for a plaque on her favorite bench in Riverside Park. Inscribed below her name and the dash between the dates are the last two lines from one of her poems.

“Door in the Mountain”

Never ran this hard through the valley

never ate so many stars

I was carrying a dead deer

tied on to my neck and shoulders

deer legs hanging in front of me

heavy on my chest

People are not wanting

to let me in

Door in the mountain

let me in

Door in the mountain let me in, I whisper to the ox, rubbing her ear.

*

I don’t know how many times my mother tried to kill herself before the morning I walked into the kitchen and she was lying on the floor, nightgown hiked up. I was nine years old and didn’t want to see her naked thighs spidered by purple veins. I leaned down to check if she was breathing, as I did when she was lying in her bedroom. I was scared to touch her. Then my older sister was in the room. She started screaming. I screamed back at her to shut up, just shut up! A switch went off in my head and I became utterly practical. I put my ear to her chest like Marcus Welby, M.D. My mother’s face was blank but her chest was still warm. That’s good, isn’t it? I walked over to the phone on the wall. Who did I call? My father? Adrienne Rich? Her sons were my best friends, they lived a block away. There were political meetings in their living room where we kids sat on the rug, awestruck by the Black Panthers. Our mothers read their poetry at the kitchen table. Adrienne was the closest mother. Who else would I call? Did I see the EMTs come with a stretcher and take my mother away or is that something I saw on TV? I know how calm I was on the phone while my sister kept screaming, but I can’t remember who I called.

Adrienne’s husband, Alf Conrad, helped me put up my vampire defenses, garlic and crosses around the bed, when we moved out of the building to a new apartment. This was after my mother’s overdose, after my parents divorced for the second time. I hated this apartment. It was smaller, and she had to sleep in the living room. I hated her for making my father leave again, and I hated him for leaving me behind.

Another school year began, and one October afternoon, I came home to find my mother on the phone, a cigarette trembling between her fingers. “Hayden found him.” The poet Hayden Carruth had identified Alf’s body in the woods. I took down the garlic and crosses. I already knew vampires could turn to vapor and come in under the doorsill. You could wake up and one of your parents had decided to disappear. Every time my mother was hospitalized, they told me that she had taken too many pills by mistake. Nobody uses the word breakdown anymore, but I like the way it encompasses so many possibilities.

Before my own divorce, my father told me that he could have asked for full custody because of my mother’s repeated breakdowns and suicide attempts. But that would have been an extreme step for a father in the 1960s and ’70s. My mother’s psychiatrist advised against it. My father, James Chace, was also a writer, a historian who was managing editor of Foreign Affairs magazine at the time. He was afraid that if he took us away from her, she would succeed in her next attempt. He thought it was better to have a depressed mother than a dead one. Of course, he said, I’ll never know if I made the right decision.

It has occurred to me that he didn’t really want full custody. My sister and I were like two people in a long, slow car accident, thrown in opposite directions.

Decades later, driving a rental car up to Vermont with my mother, we started talking about Alf and the boys. Without looking away from the road, twin yellow lines spooling out in both directions, she said, “at that moment you are very sure that everyone you love would be better off without you.”

This was a sentence fragment rather than the beginning of a conversation, followed by a brief silence. I hadn’t asked.

*

When my first daughter was born, I swore to do everything the opposite of my mother. Four years later, her younger sister made us into a triangle. I held a hand on each side. We colored their paper lunch bags and read our favorite books aloud. I was living three thousand miles away from home, part of a tight-knit group of theater artists, circus performers, and musicians. In Seattle in the ’90s we lived in each other’s pockets and pretended we told each other everything. I worked in the theater, sang with the band, and performed on the trapeze. I put the kids down on blankets in the green room. They watched rehearsals and learned to sleep through anything; I had done my homework under the kitchen table and fallen asleep at poetry readings.

I spent more than a decade coloring in different homes with my brilliant, faithless husband. I told our daughters how nomads carry a small rug and wherever they put it down is their living room. Children believe what you tell them, but by the time I was forty, I had fallen from the trapeze and become a writer with two young daughters in a marriage I didn’t want to admit was over. I was in New York the day the towers fell and a year later I moved us back, driven home by an intuition I couldn’t name. My husband returned from the road for the last time, in love with someone else in a language I couldn’t speak. My father, by then living not with his second wife but a longtime companion, died of a heart attack in Paris.

My city became abruptly unrecognizable.

I almost didn’t take the apartment around the corner from my mother. But it was comforting to return to the old neighborhood. For the past decade my mother and I had gotten together with the children once or twice a year and called each other on our birthdays. I pretended to be as thrilled as she was that her grandchildren wouldn’t even have to cross a street to visit her. My girls ran to greet her when she came to our door. I felt lucky and sad. As my marriage dissolved into night sweats and panic attacks about money, I tried hard to let her become someone I never knew. I picked up pizza and garlic knots for dinner with Grandma Jean, and read aloud from D’Aulaire’s Greek Myths. We all loved the tales of gods and heroes. I began teaching in a series of windowless classrooms, writing on trains, and smoking cigarettes on the fire escape after the children were asleep. None of this was imaginable to the teenager with a copy of Basho in her backpack. Except maybe the cigarettes.

I will not go mad, I told myself. I will not disappear.

The only way not to become my mother was to ask her for help. I decided to apply to artist residencies—she had done that, now I would too. At first I took only one week away from my daughters, then two, then three. The children stayed with Grandma Jean, watched movies, ate too much ice cream, and were happy.

*

From Shiogama Shrine, I take a ferry to Matsushima, an archipelago of rocky islands covered with twisted pines. Each one a bonsai against the gray horizon. There are hand-drawn maps at the back of nearly every translation of The Narrow Road, showing how far Basho walked in a time when few people traveled for pleasure. Basho and Sora wore monks’ robes for safety on the road, signaling they carried nothing of value but poetry, which they gave away. Then, people who might not have considered themselves poets sat in circles and wrote long sequences of linked haiku, renga; a kind of board game. Basho left haiku on doorposts as thank you notes. At Matsushima he slept with the windows open to the bay, unable to write, unable to sleep.

Islands are piled above islands, and islands are joined to islands, so that they look exactly like parents caressing their children or walking with them arm in arm.

When I arrive at the hotel, I strip off my hiking clothes and put on the cotton bathing robe, yukata, left folded in the closet. There are specific instructions to fold the robe left-over-right across my chest; they are folded the opposite way on the dead. I keep checking that I’ve tied it in the right direction. I feel shy wearing only a cotton robe as I walk down the hallway to the elevator, carrying my comb and hair clip in a plastic basket. But there is something sweetly comical about strangers passing each other in the lobby wearing flowered robes and rubber sandals, eyes politely averted. I find the small cloth squares marking the threshold of the hotel’s onsen, communal bath, and enter the misted bathing room naked. There are low stools along the tiled wall underneath rows of hand-held shower sprays. I squat down next to two other women to rinse off. The pain from my “frozen” shoulder starts to ease up as I slip into the warm bath and close my eyes.

I hardly ever saw my mother’s body. Her nakedness made me uncomfortable and ashamed despite my years of lounging in the dressing room, standing in the wings wearing only shoes and underwear as a costume assistant whipped a dress over my head. A friend who was helping her aged mother with dementia told me that she would undress with her at bath time. Her mother enjoyed her company, saying frankly, “I like your body!” I laughed at this story, hiding my undercurrent of horror at the thought of holding my mother’s slippery nakedness against my own.

*

My mother had a ten-year gap between books when she was dropped by Farrar, Straus & Giroux after her fourth collection, The Messenger. She couldn’t find another publisher. She was getting sober; it was a hard year for her when she quit drinking. But her therapist told her to write every day, whether she was published or not. In an interview with the writer Kaveh Akbar, she says:

I was suffering depression and I worried about whether the poetry was making things worse, when I saw [Plath and Sexton] going before me. I had two little kids. I had a wonderful therapist and I said, “Seeing these two suicides ahead of me and with two little children, maybe I’m on the wrong path of work.” He said, “No! Just the opposite, the poetry is for your health and they would’ve perhaps died sooner if they hadn’t had the poetry. The poetry may have kept them alive for some time.”

I cried at the back of the room at her readings, passing my hand roughly over my eyes before going up to congratulate her. She came to my book launches and told me she was proud of me, but did she read my books? I was afraid of her response to the thread of suicide running through my novels. We never discussed it.

*

I meet the other people on the Basho tour at the Matsushima hotel breakfast. A woman from Singapore is doing the walk with her college-age son. The mother is friendly and the son is quiet and polite. It’s a surprise that we are the only ones on this self-guided tour. After saying hello, I sneak glances at the two of them across the dining room. I would never have traveled this far with my mother. The treasure map tells me to prepare to be without my suitcase overnight; it will be moved to a ryokan two days down the road. After breakfast, I pack and unpack too many times, leaving my trekking poles in the suitcase and strapping on my overstuffed backpack. I leave my suitcase at the desk and keep moving.

There is a blue and white wave painted on the sidewalk, the crest at the top of a cement square, municipal signage marking a tsunami evacuation route. The islands of Matsushima Bay broke the force of the wave that hit at 2:46 pm on March 11, 2011, submerging this sidewalk graphic below a clotted ocean of trees, cars, boats, and bodies. I follow the route to Zuigani Temple, its tall entry gate down an alley behind a mall. There is a small wooden shrine dedicated to people killed by the tsunami. A post higher than my chest marks how high the water came. The early morning temple grounds are green and quiet, stacks of stone carvings lean against each other inside tall alcoves carved out of the cliff by centuries of water. These stone tablets are Habi, Buddhist grave markers.

As her bright mind loosened, I wondered if the day would come when she no longer knew me.

I see my Basho tour companions and we walk together to the train station. The son, Nick, is beginning his summer break from university in London. He completed his mandatory two years of service in the Singapore army before going off to college. He is clearly in charge of the treasure map. I linger behind with his mother, Pauline, as he leads us toward the station. We exchange information:

–Writer and teacher, New York, divorced, two daughters.

–Harvard business school, marriage and family in Singapore, divorced, two sons.

–Basho?

Not really. Japan is only a six-hour flight from Singapore and this tour fit the dates of her son’s vacation. Were you nervous to come on this tour alone? she asks.

Natagiri pass is the steepest climb yet. Basho and Sora hired a guide to slash their way through thick bamboo with a machete as they waded through streams and scrambled over rocks. Pauline loans me one of her walking poles. Nick goes ahead with the map. The light filters the green and brown forest into a Miyazaki film. Layers of pine needles muffle our footsteps and I’m grateful that the three of us can be quiet together as we walk. Every time we reach a wooden marker with a snarling graphic of the Asiatic black bear, we pound the board with a mallet hanging below to scare them away. Pauline has a small “bear bell” attached to her backpack that chimes as she walks. When we reach a stairway of logs cut into the mountain, Pauline stops to catch her breath, urging us to go ahead, but her son waits beside her, his hand placed gently on her shoulder.

*

Braided together by my daughters, my mother and I grew closer as she aged. She took my arm as I guided her to and from the apartment building she now thought was a nursing home, though she had lived there forty years. She knew there was something wrong with her memory. We placed a large calendar on the kitchen counter to help her stay oriented.

What day am I seeing my therapist?

Is the foot doctor today?

I can’t find my watch.

Is it the weekend?

You’ve got what takes most people years of meditation, I tell her. You’re fully in the present, like the Buddha.

She laughs, then turns back to the calendar.

What day is today?

Now I laugh and she joins in, though she still wants to know what day it is. I point to Wednesday and write my name on it so she’ll know I’ve been here. We have the same laugh. I sat next to her in doctor’s offices, drank tea in her kitchen, perched on the edge of her bed massaging her hardened feet, toenails curled into tiny hooves. As her bright mind loosened, I wondered if the day would come when she no longer knew me.

The night I called the ambulance, I tucked a soft wool blanket around her on the stretcher. I didn’t know if it would stay with her once she got to the hospital, but I couldn’t bear to send her away without something from home. I was hoping it would be a sign to the doctors, nurses, and orderlies: This is a woman who is loved. Treat her as carefully as the EMTs who moved her from her bed onto the gurney as if they were balancing a drop of water on a leaf.

At the end of visiting hours, I sat at the end of my mother’s bed and put my hand on her foot, curved and still beneath the wool blanket. The sun was reflecting off the tall white building across Amsterdam Avenue. I told her that she had done good work in the world, she had been a good friend and a great poet, that we loved her, that I loved her. I also told her that I forgave her. I don’t know why I said it, just then. I was sure I would be bringing her home to hospice care the next day.

In the middle of the night came the call from the hospital. The 2:30 am drive uptown along the East River from Brooklyn. The kind guard in the lobby and my mother’s terrible, open mouth.

On the other side of the pass, the smell of sulphur rises in white mist. This is Hijori Onsen, a village named for its healing hot springs, our last stop on the tour. The ryokan is small and clean, with cubbies by the door for muddy boots. Straw slippers wait in a row. I open the sliding windows next to my bed and watch the rain falling into the brown curves of the Magami river. I half-doze on my futon, and when I open my eyes there is an elegant heron standing in the water below the small metal bridge. This Japanese heron is better dressed than our great blues, with a white stripe on its waistcoat and a gleaming black beak. The bird looks like David Bowie—lean profile, bright costume, and a shock of feathers shivering up. He’s perched on a painted gold rock I’m sure wasn’t there before I fell asleep. This can’t be a tidal river so high in the mountains; how could I have missed the glitter in all this gray? Bowie stretches his wings, leans forward, and lifts into the mist.

Every onsen in the village has different healing properties: injuries, bad luck, a broken heart. I decide to try the one for injuries—I can no longer put on a shirt without shooting pain in my shoulder. It’s late afternoon and the village is nearly empty. River water rushes below the narrow street through round drainage grates. Only one store is open, its accordioned metal shutters lifted to display stacks of pink plastic brooms and aluminum cookware. I walk the length of the village, my eyes swimming through Japanese characters pasted on shuttered doors and windows. Two older Japanese couples wearing robes and rubber sandals walk toward me, their faces steaming pink in the rain. I point to the map the hotel gave me, where is the onsen for healing wounds? One of the women smiles and gestures for me to follow them into the next building. It’s warmer inside, but there is nobody at reception.

The men have left us, walking down a badly lit hallway past the desk. I follow the women through a heavy sliding door into a high ceilinged room with fat industrial spigots pouring hot water into a cement tank. I point to my shoulder and wince dramatically, still trying to find out if this is the right bathhouse for injuries, which makes the women giggle. I suddenly long for my daughters who would laugh at me just like that. The old women are already hanging up their robes, totally naked underneath. They look like their bones would splinter if they slipped on the wet floor, but they climb easily into the tank and gesture for me to join them. I hesitate, there are no buckets for rinsing off before entering this onsen, but I follow them into the hot, milky water. We float next to each other, breasts, bellies, and toes breaking the surface. They keep laughing like children with loosely tethered skin.

I think of them walking with their husbands down main street, all four naked under their robes as they shuffle along, and it’s impossible not to giggle along with them. It’s our only shared language and our voices bounce off the high cement walls until my laughter breaks into loud, messy sobs. I can’t stop, I can’t look at them, and I can’t pretend I’m not crying. I gulp air and dip my head under one of the spigots, water pounding hard. When I’m done, I let go of the wall and we float silently inside this barrel of water from the mountains.

The two old women climb out of the tank, and as my foot reaches for the step behind them, I start to lose my balance. One of them takes my arm with a hand that’s stronger than it looks, and I find my feet on the streaming floor, murmuring, origato. The three of us bow to each other, naked and soft.

*

When Basho left for the north country, a few friends gathered at dawn to see him off.

I felt three thousand miles rushing through my heart, the whole world only a dream.

I saw it through farewell tears.

Spring passes

And the birds cry out—tears

In the eyes of fishes.

There is a poem Mom wrote for her mother that I like to pretend she wrote for me.

“Mare and Newborn Foal”

When you die

there are bales of hay

heaped high in space

mean while

with my tongue

I draw the black straw

out of you

mean while

with your tongue

you draw the black straw out of me.

On the last morning, I wake up early. A taxi will take us to the train station, until then I can dream whatever I want. My rubber sandals slip on the paving stones next to the Magami. The gold rock is underwater. My daughters and my mother wait for me, naked under our cotton robes.

__________________________________

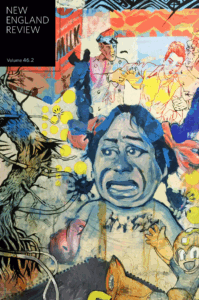

“Pilgrimage” by Rebecca Chace appears in the latest issue of New England Review.