Back in September, in a measure designed to “prevent immorality”, the Taliban closed down the internet in Afghanistan. This was the latest step – after a ban on all girls over the age of 12 receiving an education, and the removal of all books written by women from universities – to restrict citizens’ access to information that the regime might consider dangerous or difficult, or that challenges their ideological monopoly. The effect would have been to ensure that an entire generation of Afghans failed to reach their potential; the connection was partly restored 48 hours later, after widespread condemnation.

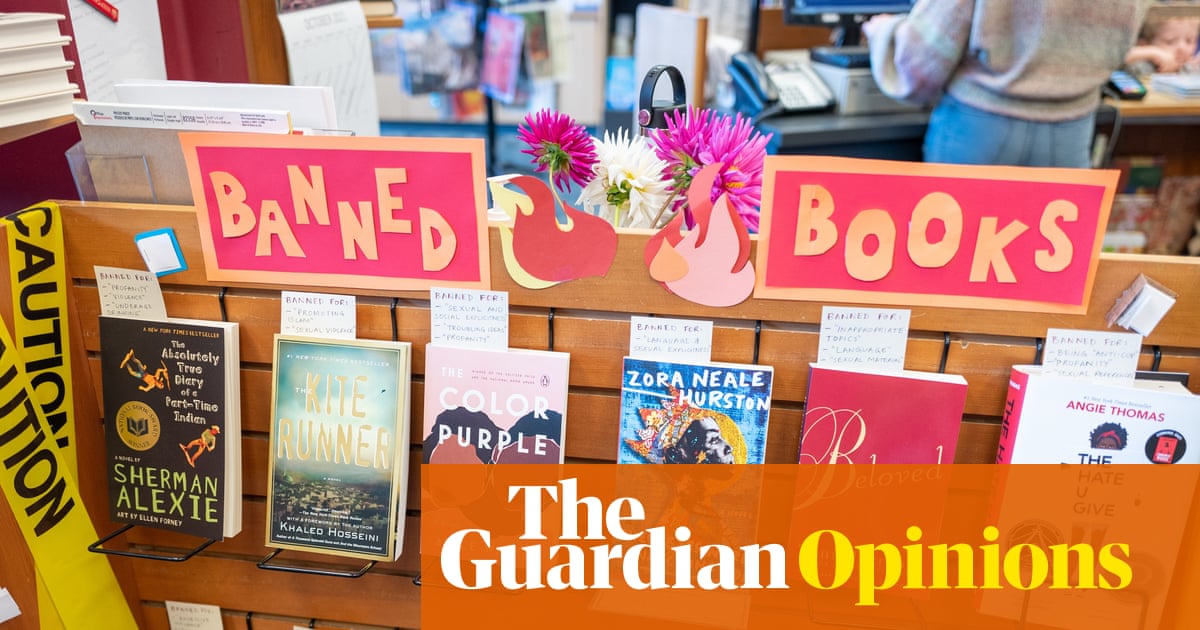

It was against this backdrop that I read about the school in Weymouth, Dorset, that had removed American author Angie Thomas’s wildly popular young adult novel The Hate U Give from its Year 10 reading list, apparently in response to the objection of one parent, former Conservative councillor James Farquharson. While copies of the book would continue to be available in the school library, its removal from classrooms sent a worrying message: that one man’s comfort could be considered more important than the rights of an entire student cohort to access literature that might speak directly to them, never mind that it may contain dangerous or difficult ideas.

I spoke to Vicky McNab, whose four mixed-heritage children have attended the school, and who launched a campaign to have the book reinstated (after an internal review, the school confirmed that the book will return to the Year 10 reading list). She shared with me Farquharson’s original letter to the school; he seemed to misunderstand or not appreciate the importance of teaching that racial injustice exists in America, as illustrated in the novel by the killing of a Black teenager by a white police officer.

To avoid such difficult ideas gaining traction in the UK, he suggested it was the school’s duty to “select books that will teach pupils their cultural inheritance”. By implying all students share a single cultural inheritance, he seems to be residing under the belief that we are or should be a monoculture, and the overriding mission of our schools should be to reinforce some sort of nationalistic hegemony to which everyone, regardless of background, must pledge unwavering allegiance. The question then arises: who was he seeking to protect?

The use of my novel, Pigeon English, is also under review at the school, thanks again to Farquharson’s intervention. His objections to my book – which he shared on Facebook having read the first 13 pages and Googled some reviews – centre on its use of profane language and depictions of violence and sexual behaviour. Pigeon English explores some of the same themes as The Hate U Give, social injustice chief among them. It draws on my experiences growing up on a diverse and deprived council estate in Luton in the 1980s and 90s, and on the killing of Damilola Taylor, the Nigerian schoolboy stabbed to death in Peckham, London, in 2000.

The novel was very much directed at an adult readership, which I felt could parse some of its more troubling content and recognise the urgent social questions it posed. I did not predict that it would end up in the hands of schoolchildren or being dissected in classrooms; nor was I consulted when the decision was made in 2015 – rubber-stamped by a Conservative education secretary – to include it on the GCSE curriculum. But its continued use as a set text suggests that teachers see in it an opportunity, rather than a threat. An opportunity to discuss, in the controlled and collaborative space of the classroom, themes and topics of particular relevance to the lives of their students.

This has been borne out by the feedback I have received over a decade of visiting schools up and down the country where Pigeon English is used either as a GCSE text or as a class reader for younger age groups. Teachers report that the book engages their students at a deeper level than other texts at their disposal, while students routinely tell me it is the first book they have studied that represents a world they recognise and includes characters they can relate to. This makes them feel seen as individuals, as well as part of a community bound not just by their real-life familiarity with events similar to some of those described in the book, but by the collegiate experience of reading and studying it together. It might also initiate a connection to the broader world of literature and the arts that can be a lasting source of revelation in their lives.

To deny students that kind of opportunity just because they may have to traverse some difficult terrain along the way would be to inhibit their progress towards fulfilling their own potential. In my conversations with them, I do not see young people who have been traumatised by the experience of reading my book. I see in their smiles the pleasure of emotional engagement, and in their eyes the fire of intellectual challenge. Like it or not, kids relate to difficult content, in ways their parents and the adult world may not entirely understand or approve of. By providing them with opportunities to discuss that content – to find the social and political context, to analyse cause and effect, to unpack the psychology of why good people do bad things – we teach them empathy, resilience and critical thinking, and train them to enter a world where a command of those faculties is more vitally important than it has ever been.

There are many things those who would ban books could be said to lack – reason, perspective, humility – but I would suggest it is their deficit of courage that defines them; or, to put it another way, their fear of discomfort. Perhaps it is the same fear that decrees the heroes of our novels should be sympathetic and relatable, that art should only depict humanity at its best and least offensive. But what can we really learn about ourselves by avoiding the messy and imperfect reality?

When Caravaggio’s Madonna di Loreto was unveiled in 1606 it scandalised Rome; not because it dared to put a face to the newborn Christ but because it showed the dirty feet of the peasants who knelt to venerate him. Centuries later, do those same prudish sensitivities still prevail? I have learned more about the human condition from looking at those dirty feet than from the halo around the holy infant’s head.

When I think about my own formative reading experiences, an instructive discomfort pertains to them all. The discomfort of learning that Jim was enslaved in Huckleberry Finn; of discovering that Paddy Clarke’s parents were unhappy in their marriage, just like mine were; of observing, in Slaughterhouse-Five, that the human capacity for cruelty, if left unchecked, could reduce entire cities to ashes. The discomfort of simply trying to figure out, aged 17, what the fuck Ulysses was about was joyful and life-changing. From those discomforts my character was formed; they gave rise to my intellectual curiosity and emotional inquisitiveness, to my sensitivity to injustice, and to my deep compassion for humanity in all its flawed and magnificent diversity. They connected me to the world; and if you feel a part of something, rather than estranged from it, you’re more likely to want to work in its best interests.

The modern trend towards avoiding discomfort – medicating against it with performative bigotry and Labubus, with flag worship and chatbot therapists – steals away our vigilance and opens the door to tyranny. To see this, we need only look at the success Nigel Farage and Reform UK are enjoying in fomenting distrust and division for their own political ends. People denied the practice of sitting with their discomfort become, inevitably, desensitised to the discomfort of others. This leads to a deficit of empathy.

Discomfort and disorder are the world’s prevailing forces, and books remain one of the best tools we have at our disposal for preparing young people to navigate them. A good teacher – and schools up and down the country are full of them, national assets too often underappreciated and taken for granted – will guide a student through their discomfort, helping them to find clarity of thought within it. This way, a school becomes a breeding ground for empathy. If we are to survive the culture wars, these breeding grounds will be essential.