The following is from John Gregory Dunne’s Vegas. Dunne (1932–2003) was a journalist, novelist, screenwriter, and memoirist. His books include five novels, seven works of narrative nonfiction, and a posthumous collection of essays. He and his wife, Joan Didion, collaborated on many screenplays, including The Panic in Needle Park, Play It As It Lays, the Barbra Streisand version of A Star is Born, and True Confessions. Two of his books, The Studio and Monster: Living Off the Big Screen, are about working in the movie business.

In the summer of my nervous breakdown, I went to live in Las Vegas, Clark County, Nevada. It had been a bad spring, it had been a bad winter, it had been a bad year. In the fall I had gone to take an insurance physical. The insurance office was on the nineteenth floor of an antiseptic new building on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles. It was surrounded on every side by a moat-like parking lot, every parking space neatly marked by diagonal lines, white for transient parking, yellow for monthly parking, green for the building’s maintenance personnel. From the window in the doctor’s office I could look across the street at a neo-Polynesian barn, headquarters of one of the largest rental agencies in Los Angeles. Revolving on the roof of the building was a neon sign advertising

Article continues after advertisement

EVERYTHING FOR THE PARTY OR THE SICK ROOM

Banquet Tables Wheelchairs

Card Tables Walkers

China Traction Lifters

Silver Commodes

Glasses Oxygen

Bars IPPB Units

Tents Crutches

Canopies Whirlpools

The examining physician’s name was Virgil Isador Kerides. He was, he informed me, a Greek Jew. He said it was a problem. I am always being told things like that on first meeting, being told by strange women that they have cancer of the uterus, by men on airplanes that they have a colored mistress in St. Louis. Never black, never Negro, always “colored.” I have never learned how to react, never comprehended why I am selected for these intimacies. Perhaps it is a penance for the deaf ear I turn to the problems of friends. I cannot bear to listen to why they are leaving their wives or how they are treating their alcoholism. “Really,” I say to these strangers with uterine malignancies, or “I see.” I never do see.

What I did see about Virgil Isador Kerides was that he was wearing one black shoe and one brown shoe and that a daub of egg yolk had adhered to his tie. I am interested in things like that, as I am interested in the layout and color coding of parking lots. I am interested in overheard conversations in restaurants, in the mosaic of petty treasons that decorate small lives. It is a hobby without emotional investment. I wonder by what act of fate a promising medical student becomes an aging doctor for an insurance company, wearing one black and one brown shoe, a Vaseline-coated plastic glove on his hand, every day invading and investigating the rectums of strangers. I wonder and do not ask. My wife says I am clinically detached.

Virgil Isador Kerides stripped the plastic glove from his hand and began taking my blood pressure. He had noted on my form that I was a writer. He said that he was interested in writing. He thought he would try his hand at it. There were a number of medical shows on television that season. He wondered if they would need a technical adviser. I suggested he write the producers.

“I’m probably too late,” he said. “I’ve always been too late.”

“Really,” I said.

“Maybe I could write an exposé of the medical shows for

TV Guide.”

“Maybe.”

He busied himself with my chart. Blood pressure normal. EKG normal. EEG normal. Prostate normal. No known diseases. Chronic indigestion probably due to overweight. The policy was for $100,000, payments $450 per quarter. I was thirty-seven years old and I was insurable, a good risk.

I put on my clothes. There was one thing, Virgil Isador Kerides said. It was not medical, it would not hold up the issuing of the policy. Had anyone ever told me that I had soft shoulders?

I asked what it meant.

“Nothing. They’re just . . . soft. You’ve got soft shoulders.”

*

Soft shoulders. If ever there seemed a perfect metaphor for my life that season, that was it. I did not seek another diagnosis. I was not concerned about muscular atrophy or neurological disintegration or pulpy bone marrow. With some dim psychic instinct Virgil Isador Kerides, who found it a problem being a Greek Jew, had intuited what I already knew, that there were other renegade cells eating away at the tissues of my life.

The metastasis had started a year or two before. When I was younger, and other people turned thirty-five, I had found it amusing to send a two-word birthday telegram. The wire simply read, “Halfway home.” But the spring I reached thirty-five, the joke suddenly seemed pallid. Perhaps it was because I began to find the names of classmates appearing in the obituary notes of my college alumni magazine. “After a short illness . . .” the notice would begin. It was a chilling phrase. There was at least something youthful and abandoned about a drunken-driving accident or skiing into a tree. I began to note in my diary the date of my annual medical checkup. I examined myself for lumps and bumps. I heard with dark dread a doctor tell me that he was sending a piece of tissue “down for a biopsy.” I became quite simply, for no real reason, terrified of dying.

The obsession evidenced itself in small ways at first. I hated to fly on planes with minor celebrities and second-string newscasters and the failed offspring of prominent people. I got off a crowded flight once rather than sit next to Elliott Roosevelt. The headline had already formed in my mind: “Crash Kills FDR Son and 92 Others.” There were reminders of mortality everywhere. Snowbound in a motel in Montana, I opened a letter that had been forwarded to me. I did not know who sent it, there was no return address. All it contained was a one-inch clip from The New York Times: someone I had known at school had fallen in front of the 8:12 commuter train from Noroton to Grand Central and was killed instantly. I had not even particularly liked this fellow, but there in that Best Western Motel in Great Falls, Montana, I remembered with febrile clarity the last time I had seen him. It was perhaps fifteen years earlier, the night before he went into the Marine Corps. I had run into him on the street in New York, and as a going-away present I bought him what in the fifties used to be called “a piece of ass.” The girl was a prostitute who lived in an orange-painted basement apartment over near the East River. She charged twenty dollars for what she referred to as “two pops.” The girl did not understand that I did not want to share in the present, nor did I even want to watch. Instead I sat in her living room leafing through a portfolio of dirty pictures. I could hear them bargaining in the next room over a third pop. He did not wish to pay, she tried to persuade him to get me to ante up another ten dollars. It was nearly dawn when we left the apartment. His train for Quantico pulled out of Penn Station at 6:30 A.M. We walked through the deserted streets and we had nothing to say. We shook hands at the gate; the next time I heard of him was after his appointment with the 8:12 out of Noroton.

I began to wonder if my death would merit a “Milestone” in Time. Would the editors consider me Milestone material? (“He used to work here,” I could imagine them saying, “never made senior editor.”

“What did he do after he left. Or was he fired?”

“Left, I think.”

“Wrote a couple of books.”

“Really.”

“It’s between him and that Dionne who checked out.”

“Let’s go for the quint.”)

My temper, always volatile, turned explosive. One day on Sunset Boulevard a boy in an Austin-Healey sideswiped me and drove my car up onto the sidewalk. “You motherfucker,” I screamed after him.

The Austin-Healey ground to a halt. The boy and his girlfriend got out of the car and walked back to mine. He was wearing a buckskin jacket and cowboy boots, she sandals, jeans and an Indian blouse with no bra. I surveyed her tits.

“What you call me?” the cowboy said.

“Motherfucker,” I said. “M-O-T-H-E-R-F . . .”

“You want a belt in the mouth?”

“What are you trying to do? Impress the cunt? Mr. Tough?”

“Tougher than you, motherfucker.”

We squared off there at high noon on Sunset Boulevard, across from where the Garden of Allah used to be, where Robert Benchley and Scott Fitzgerald and Dorothy Parker had lived, their conversation I am sure a good deal brighter than the “cunt” and “motherfucker” being bandied back and forth between the boy in buckskin and the thirty-seven-year-old lunatic in a gray Firebird convertible. I took the first swing, hitting him high on the cheekbone, and for my daring got a cowboy boot squarely between my testicles. I lay on the sidewalk, holding my nuts and moaning in pain, watching the boy and his girl drive insolently off in the Austin-Healey.

The empty days were riven with other indignities. I went to a doctor to see if there was any medical reason why I had been unable to conceive a child. Not that I even wanted to. My only child was adopted and there was no chance that anything produced by my genes could come close to equaling her. But it was something to do, a day-waster. The doctor said there were two ways to check my semen, either via what he called “self-gratification” or with the seed of coitus interruptus. I chose the former; since the semen had to be in his office no more than forty-five minutes after climax, there was a “Beat the Clock” ambience about the latter that I found intimidating. The timer raised his gun. Ready: On the mark: Get set: Go. Out of bed and into your clothes. The car engine was idling. East on Palos Verdes Drive. South on 26th Street in San Pedro. Onto the Harbor Freeway. Change over to the San Diego Freeway. Off at Wilshire Boulevard. If the lights were with you and the car was in tune, it was a forty-three-minute Emission Possible. Self-gratification seemed more meaningful.

The doctor’s nurse gave me a natural lambskin rubber prophylactic and the directions to the men’s room. I sat in a stall trying to coax some heft into my flaccid member, terrified that the cubicle door would be flung open and I discovered with a lubricated rubber dangling between my legs, like some refugee from a bus station or a Y.M.C.A. men’s room. I tried to conjure up breasts and pudenda, a difficult task when the theme music was the constipated grunting from the adjoining stall. Someone at the urinal began crooning:

“You’ve got to live a little,

Laugh a little,

Always have the blues a little,

That’s the story of,

That’s the glory of

Love, love, love.”

The minutes ticked away. I imagined the nurse in the doctor’s office checking her watch, wondering what kind of auto-perversion I was into. I made a mental list of every woman I had ever had intercourse with. The number was twenty-eight and none of them were giving me any help. Love, love, love. Whom had I wanted to fuck and never had? Movie stars, the wives of friends, dogs, cows, anything. Nothing. Love, love, love. Carmella Manupelli, seventh grade, Verbum Dei School, Hartford, Connecticut, the first girl I ever knew who wore a brassiere, now a Little Sister of the Poor in Chicago. Bingo.

I put the rubber in a prescription box and gave it to the nurse. She accepted it as if it were a prune Danish from the coffee cart. I still had the condom’s foil covering crumpled in my hand and did not know what to do with it. The reception-room wastebasket did not seem the place for it, so I just held it in my fist. I regarded the other patients, fairly certain that I had whacked off more recently, or at least more recently in a bizarre environment, than any of them.

It was nearly an hour before the results were in. The spermatozoa had passed the test.

“They won’t win any races,” the doctor said. “But they get there.”

I asked the forgiveness of Mother Mary Stella Mare, formerly Carmella Manupelli. The race was not always to the swift.

__________________________________

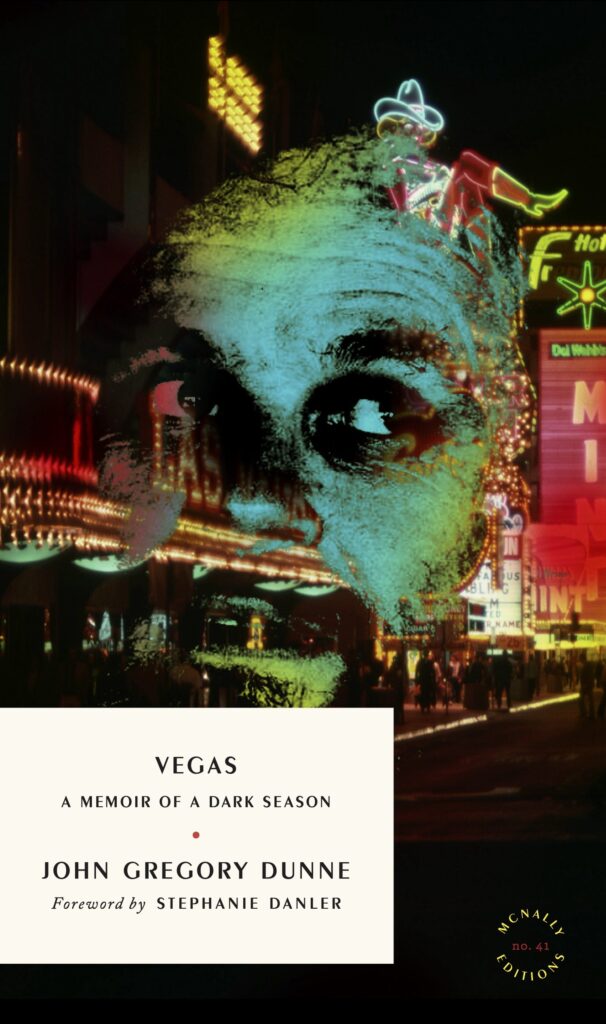

From Vegas: A Memoir of a Dark Season by John Gregory Dunne. Used with permission of the publisher, McNally Editions. Copyright © 2025.