June 24, 2025, 2:07pm

If you suspect that ChatGPT power users may be getting dumber—looking at you, Cuomo and RFK Jr.—the data seems to indicate that you’re right. A new study by scholars from MIT and Wellesley, titled “Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task,” set up a months-long comparative experiment that measured the brains and essays of some student writers, and found that AI “[large language model] users consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels.” Not only that, but the negative effects of using AI remained measurable in the participants afterwards, and even when they were doing their thinking without LLMs.

So how did this experiment work? 54 students were broken up into three groups and asked to write SAT-style essays under different conditions: one group used an LLM, another used Google Search, and another used only (gasp) their brains.

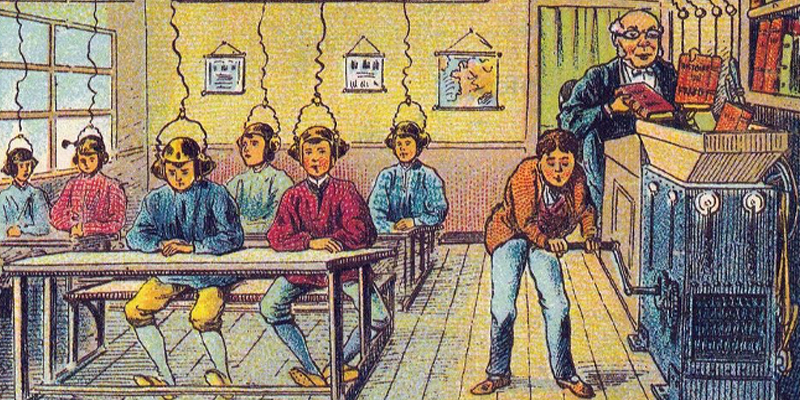

Each writer completed three timed sessions using their assigned tools, and their writing time was recorded using interviews and brain scanning helmets using electroencephalography (EEG), a method to record the brain’s electrical activity. Their essays were then judged and quantified by humans and AI—this isn’t a group of scientists who necessarily have it out for the technology.

In an optional fourth session—18 chose to do it—the writers were asked to swap tools. LLM group participants were asked to use only their brains, and the Brain-only group participants were asked to use the LLM.

How did it go? The conclusions are pretty stark:

… we demonstrate the pressing matter of a likely decrease in learning skills based on the results of our study. The use of LLM had a measurable impact on participants, and while the benefits were initially apparent, as we demonstrated over the course of 4 months, the LLM group’s participants performed worse than their counterparts in the Brain-only group at all levels: neural, linguistic, scoring.

There’s a lot in the study, but some conclusions stood out.

The paper found that the process was better on the brain without tech tools: “internal attention and semantic processing during creative ideation” was highest for the writers who used neither Google nor ChatGPT. The final essays were different too, with best writing coming out of the Brain-only group, which had the most unique text in terms of expression and vocabulary.

The study also looked at how the essayists reflected on their own work. There was a vast gap in participants’ abilities to quote themselves: nearly 90% of ChatGPT users struggled to quote themselves, as opposed to just over 10% of search and brain-only writers.

I found this chart to be interesting too:

The idea of feeling ownership over your writing is a squishy thing to quantify, but it’s telling that the LLM participants, who were the least invested in the process, responded with the least investment and ownership in the final essays.

It’s no surprise, since the study’s description of the LLM group’s process is bleak:

Most of them focused on reusing the tools’ output, therefore staying focused on copying and pasting content, rather than incorporating their own original thoughts and editing those with their own perspectives and their own experiences.

Copying and pasting is clearly not as enjoyable as thinking and expressing yourself: “participants who were in the Brain-only group reported higher satisfaction,” the study reports.

And when asked to reflect on the tools, what they wrote, and why, the study found “most participants in the Brain-only group engaging and caring more about ‘what’ they wrote, and also ‘why’… while the other groups briefly focused on the ‘how’ part.”

The old cliche seems true, that writing is tough, but having written is wonderful. The labor dignifies the creation.

The offloading of our thinking and memory to tech tools is reaching a new extreme with large language models, but the scientists are clear that this isn’t something AI introduced. This started with search engines. The paper discusses the “Google Effect,” which “can shift cognitive efforts from information retention to more externalized memory processes.” That is, because we know information is just a quick search away, we’re disincentivized to remember anything specific, and instead “retain a strong recall of how and where to find it.” LLMs only exacerbate this trend: habitual LLM users have a tough time remembering the information AND the process to get the information.

Since this experiment involves writing high school style essays, a diversity of ideas and sources was part of the prompt and process. But LLMs continually steer users into echo chambers:

This occurs because LLMs are in essence ‘next token predictors’ that optimize for most probable outputs, and thus can potentially be more inclined to provide consonant information than traditional information system algorithms …The conversational nature of LLM interactions compounds this effect, as users can engage in multi-turn conversations that progressively narrow their information exposure.

The most frightening conclusion, and the one that’s jumping out in the coverage, is that the deleterious effects of using ChatGPT didn’t go away. Frequent LLM users maintained a “cognitive debt” in the final session, when they were asked to switch to brain-only writing:

The LLM group, while benefiting from tool efficiency, showed weaker memory traces, reduced self-monitoring, and fragmented authorship. This trade-off highlights an important educational concern: Al tools, while valuable for supporting performance, may unintentionally hinder deep cognitive processing, retention, and authentic engagement with written material. If users rely heavily on Al tools, they may achieve superficial fluency but fail to internalize the knowledge or feel a sense of ownership over it.

And the opposite was true for the students making the brain-to-LLM switch. Their essays were more complex and unique, they felt more ownership, and they “showed higher neural connectivity than LLM Group’s sessions 1, 2, 3.” It’s remarkable: even using an LLM, students who had previously practiced using their brain showed more brain activity than the users who started with LLMs only.

It’s pretty damning for AI boosters who says that learning to write will soon be obsolete. Both the process and the final writing were richer and more rewarding, regardless of the tools used, when students had experience using their brains. The danger is that the study also makes clear that the LLM users spent less time on writing:

LLM users are 60% more productive overall and due to the decrease in extraneous cognitive load, users are more willing to engage with the task for longer periods, extending the amount of time used to complete tasks.

This is the crux of the appeal for pro-AI camp in my experience: it’s about efficiency. A faster result is seen as an unimpeachable good. But that seems like a grim trade-off when users also don’t care about the process, or the final product, and can’t even remember much about what they made.

At the same time, I get that school can feel dull and tedious, and less time doing homework essays is clearly appealing to many kids. As 404 Media reported, classrooms are already awash in LLM use and it’s already a very present challenge for teachers.

What can you even say anymore? These LLMs are simply not good. “But James, think of the applications! AI could be a useful tool!” Maybe, but why use a tool that is disconnecting the neurons in your brain? I wouldn’t use a hammer that not only misses the nail I swing at, but also bounces back and clocks me in the head.

Frankly, I’ve got enough in my life that is rotting my brain and making me feel bad—I’m not eager to add another.