While planning this interview, my sister and I were on the phone (as we are most days) and I said I would write up the introduction and she said I should send it to her for edits and then she said SHE would write it up and send it to ME for edits, and things generally devolved from there about who wrote “turgid prose” (me) and who was bossy and annoying (her).

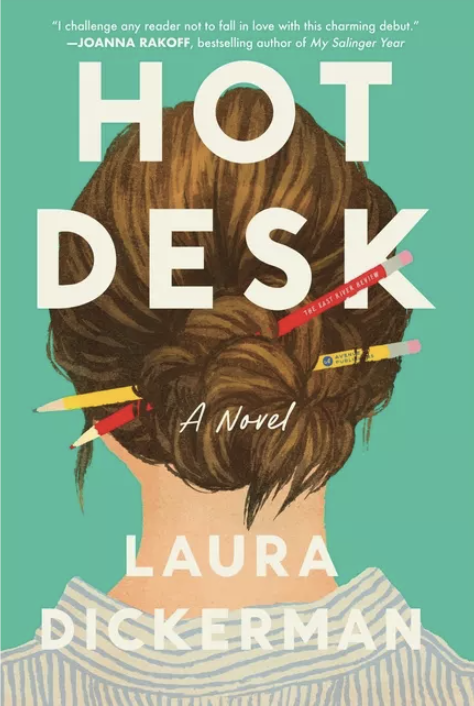

This banter was much in evidence as her debut novel, Hot Desk, came into being. I delivered the spark of an idea for the book (literally one line), but knew I didn’t have the time or the talent to write it. My sister had both.

Since half the book takes place in a contemporary publishing office, where I have spent over 30 years, I could provide details about zoom meetings gone awry and the indignity of phone pods. But for the second timeline, New York City in the early 1980s, she delved into her own experience working as an intern at The Paris Review to bring those sections vividly alive, and eventually my role was mostly relegated to harassing her via a talking panda emoji to HURRY UP AND FINISH.

Connecting over Hot Desk brought us back to our childhoods, our love of books, and the bond we have always shared. Six years older, she did everything cooler first. And I happily followed in her footsteps. She would probably say shadow. We both majored in English and worked at the college literary magazine. We both spent a year studying literature at the University of Edinburgh. We both interned at The Paris Review. But she was always a writer, and I was just a voracious reader, and then an editor.

What follows is a transcript of our conversation about what it’s like to be siblings interested in the same things, how reading prodigiously and maybe a bit recklessly as children shaped us, how our paths led us first to different places and then to Hot Desk. Though we are both controlling, opinionated, and foul mouthed, most profanity has been cut.

*

Colin Dickerman: My earliest memory of perhaps having read too much, too early, was writing something in a (well-deserved) burn book aimed at a very obnoxious 4th grade classmate. My entry unfortunately quoted a particularly vicious line from a Stephen King novel. When the teacher confiscated it, she was “disturbed” I knew such a “sophisticated” insult. Yes, I remember what it was (shame cuts deep), and, no, I won’t tell you. Did you ever have a similar moment of reading beyond your years in a way that got you in trouble or somehow had a negative impact in the real world?

Laura Dickerman: God, we read everything all the time! I remember going to the Shelburne Library once a week and checking out an enormous armful of books then sitting on the couch and reading straight through. Anna Karenina and Flowers in the Attic in the same haul. I mean, how were kids allowed to read Flowers in the Attic? I never used my sophisticated knowledge for evil as you did, but I do recall the humiliation of confidently mispronouncing words I had only ever read: melon-cholly for melancholy and chick for chic and col-lone-el for colonel, etc. I am lucky that I drowned out the horror of Flowers in the Attic with many, many bodice-rippers.

CD: I think one of the greatest benefits of having read so much as a kid, particularly “adult” books, is that I never had to ask our parents one question about sex. That, and being super popular when I brought Judy Blume’s Wifey to school, with all relevant passages dog-eared. What benefits did you see?

LD: Judy Blume’s Forever was my Bible. Look, you already made me cut all the sexiest parts in Hot Desk, so close your ears, but reading spicy romance novels with women being seduced by brooding men who were very invested in women’s pleasure set me up for a lifetime of expecting, if not slipping my silk chemise off in front of a roaring fire and being ravished on a bearskin rug, then at least that a lover took his time and knew what he was doing.

CD: I always appreciated our parents’ completely laissez faire attitude about what I read and still remember being proud that the librarian knew I had permission to take out the one copy of Go Ask Alice kept behind the counter. Had they just given up, because I was the youngest (and clearly the smartest and most successful child)? Or were they equally permissive with you?

LD: I ran so you could fly. One of my clearest memories from the early 1970s is visiting relatives and sleeping on a pull-out couch in their library. Mom, who had never, not once, said anything about any of the books I read (see Flowers in the Attic) came in and very seriously told me that Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying was off limits. The minute she left I could not get that book in my hands fast enough and stayed up all night to finish it. It did not hold a candle to the graphic detail of the bodice rippers and all of those zipless fucks I had already encountered in haylofts, carriages, garden mazes, and on bearskin rugs.

CD: Reading, for me, was a huge escape, and given the rather draconian rules around TV in our house, a fantastic way to pass the time. In retrospect, I think it helped me, a gay kid, lose myself in other realities. What kept you turning pages?

LD: Right, we were allowed to watch TV on Sundays only: Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom straight into the Disney movie of the week. When the tennis team was singing the Brady Bunch theme on the bus to a match, I was faking it. Pop culture didn’t have much of a hold on us yet, and reading, to me, was not so much an escape as a portal. What I mean is that I loved my life growing up in Vermont, but I was fascinated by other worlds—in particular, secret gardens and windswept moors and magical wardrobes—and reading showed me that imagination was unlimited. I was also drawn to books with strong girls and women: Caddie Woodlawn, A Little Princess, Emily of New Moon, of course Jo March from Little Women, Elizabeth Bennet from Pride and Prejudice. I already had a sense of myself as a writer (lots of poems about horses) and reading reinforced that for me.

CD: Our father was a doctor who very vocally wanted to be an English Professor and is still obsessed with Herman Melville, and here we are, an editor and an ex-English teacher and now novelist. For me, his dilemma always translated into “do the best you can, so you can make whatever choices you want in life.” Which isn’t exactly NOT pressure, but sort of a positive spin on pressure? Did you feel something similar? Even when you got that D in French class and were grounded?

LD: That was after I had already been accepted to college! As a creative writing major at Hamilton! A draconian response to a tiny senior spring slide, in my opinion. I recall more of a “Do whatever you want to do, but do the absolute best you can at it”—be the best ditch digger in the world vibes. I’m sure a therapist would be interested in how our father’s passion for books or, as he likes to say and we like to mock, “littt-tra-chure,” informed our choices, but I can do the work: he was, as you said, very up front about being forced into medicine as a safe career by parents who had lived through the Depression, but he was invested in our doing what we loved, which, according to him, was what he loved. And why not?

I adored being ushered into his den, crammed with all the Melville paraphernalia, tomes of the British and early American authors he preferred, and that dusty bagpipe on the wall, to listen when he read “The Song of Hiawatha” and “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” I can still hear the cadences of those poems. One of my proudest moments was when he visited an English class I taught at the Collegiate School. Though he was probably disappointed I was teaching Sharon Olds instead of Hawthorne that day.

CD: I remember our mom was a BOTMC member, and I read everything behind her, including Jean Stein’s book about Edie Sedgwick, which blew my mind for every possible reason, since I think I was 11 when I read it. Maybe this wasn’t the intended message of the book, but it certainly cemented in me the desire to move to NYC as quickly as possible and get into some trouble.

Did you have a similar moment where you read about a time or place or group of people that helped you shape your idea of what your future might be? And, yes, I know Warhol’s factory was full of louche, drug-addled, deviant lunatics, but they certainly had more fun than we did in rural Vermont.

LD: What wasn’t fun about gathering around the bonfire drinking beer from a keg at the lake access? Do you remember visiting Grandma and Grandpa in the apartment where our dad grew up on the Upper West Side? They would take us to Chinese restaurants, which were the absolute most amazing experience for me. And our Mom’s parents took us to the opera. So I was well aware early on that NYC was the place to be. From the Mixed Up Files of Mrs. Basil E Frankweiler, about the brother and sister who lived in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the All-of-a-kind Family series about the Jewish sisters on the Lower East Side, were my touchstones, not the deviant lunatics that drew you in.

CD: So, six years after you moved to New York, I followed you there, only to find you sporting Liza Minnelli sideburns (“They take getting used to, but you will!”) taking writing workshops and then teaching English. I went straight into publishing and never looked back. I have many fond memories of that time, the first when we found a big bag of weed in the back of a cab and you subsequently got lost trying to find the concession stand while we were seeing The Nightmare Before Christmas. The second is when you worked—for a brief, glorious time—as my temp at the Atlantic Monthly Press. How the tables had turned! Ok, this isn’t really a question, but what are some of your fun memories of that time?

LD: It was more a Louise Brooks vibe I was after with that haircut. You might think I learned my lesson after the tragic Dorothy Hamill cut in the late 1970s. You got a job working with Gordon Lish at Knopf (another word I can read but neither pronounce nor spell) and I was going to poetry readings and trying to get into Limelight. Jesus, I remember wandering that enormous movie theatre complex for what felt like days. You were a cruel and exacting boss at the Atlantic who complained about my not being able to replace the toner on the copying machine. That was a PhD level skill!

I was so precious that one Halloween I dressed as Susan Sontag (white streak in my hair and black pants). The subways were still plastered with graffiti, and you lived in an apartment down under the Manhattan Bridge like a little troll. We used to go out to fancy dinners with Grandma. I based the character of Mimi in Hot Desk on her—her love of a stiff gin cocktail and a good story and a great restaurant. She kept tins of escargot in her tiny kitchen. I remember you did a book with Jon Stewart and wrangled me an invitation to his book party. I knew he would become my husband. He did not.

CD: God, Grandma was the best. She had “quit smoking years ago” but always came right over to me for a puff, even when she was dragging her oxygen tank. Anyway, about 20 years ago, I gave you an assignment to write a YA novel about a boy who falls in love with a ghost. YA was just getting really hot, and I was certain we were going to be massively successful. Helping plot that book with you was such a blast, and I know you had a great time writing it. Sadly, it went nowhere. What was that like for you? For me, of course it was disappointing, but it also cemented what I already knew—that we could collaborate on something and have a great time doing it.

LD: As an English teacher, I love an assignment! What’s so interesting to me is that the two books I wrote (besides the fact that they were both spurred by a prompt from you) were in genres that I didn’t think were “my” genres. I had thought of myself as certain kind of writer, a graduate workshop kind of writer I guess you could call it, with the pressure that comes to be literary in a particular kind of way. The supernatural YA book poured out of me, I think partly because the words “supernatural YA” freed me from worrying about being the next Virginia Woolf. It was, if not a crushing blow, a great disappointment when that book didn’t garner us fame and fortune.

I basically took 20 years off to sulk about it and raise a family. But you’re right that navigating that project together was incredibly fun. I mean, one of my absolutely favorite things to do is to drive around Vermont with you and our other brother, James, listening to classic rock on 106.7, the Wizard. James read a lot of history and sports books then became a lawyer.

Anyway, 20 years later, after my kids were out of the house, you came up with the assignment to “Write a novel about two rival editors who are forced to share a hot desk and fall in love” that also unlocked a torrent. Thinking at first of Hot Desk as a romcom allowed me to write in what I discovered was not only my speaking voice but also my writing voice if that makes sense. As the funniest sibling, I leaned into that strength. And nothing made me happier and more motivated than when I would see your comment “this is so good!” on our shared Google Doc.

CD: I know you’re working on a new novel, which was NOT my idea. But I will always be your first editor!

LD: Oh, don’t worry, I will be sending you the dreaded Google Doc for feedback! My next book (all two chapters of it so far) takes place in Vermont and features an eccentric, irascible character based on our father. So you will be needed.

___________________________

Laura Dickerman’s Hot Desk is available now from Gallery Books