I’m sitting cross-legged on top of a picnic table at Biloxi’s Riverside Park, facing Bay Area writer Julia Scheeres. Behind us the muddy brown waters of the Tchoutacabouffa River roll towards what until recently was commonly understood to be the Gulf of Mexico. My long hair is twisted up on my head, because it’s muggy the way it only gets in Mississippi, the state where I was born and raised. As I try to explain the intensity of the summer heat to Scheeres, she shows off a brilliant red ring around her ankle, souvenir of another Mississippi staple, her first fire ant attack.

Article continues after advertisement

The two of us have just been on a walk; I’d driven seven hours from Georgia, where I live now, to meet up with Scheeres, because, even though we’ve known each other since the 2005 publication of Scheeres’s groundbreaking memoir, Jesus Land, we’d never met in person. We’re both in Biloxi, because, over two decades after Jesus Land was released, it’s being made into a movie, filmed in the nearby working-class community of D’Iberville.

*

Scheeres’s memoir Jesus Land recounts how Julia, a white teenager from a strict Christian family in Indiana, followed her adopted Black brother, David, to Escuela Caribe, a brutal reform school in the Dominican Republic, which was run by white evangelicals, many of whom most likely identify now as Christian nationalists. There Julia and David, who is now deceased, were subjected to levels of oppression so extreme it’s almost impossible to understand unless you went through it—later when Scheeres wrote A Thousand Lives, her book on Jonestown, survivors who’d never spoken to anyone before trusted Scheeres “because you get it.”

Not only was Julia and David’s mail censored, but who they spoke to, if they were even spoken to (many students were punished with a form of silent treatment), how they were spoken to (Escuela Caribe utilized attack therapy, a form of group therapy where the client is humiliated, to control behavior), and how they even moved was controlled. All students were forced to perform long hours of physical labor, while also being subjected to unrelenting physical, emotional, spiritual, and, at times, sexual abuse. And even though all students at the school were oppressed, the punishment inflicted on David was even more intense, due to the staff’s often outright racism.

“It’s worse than the Reagan years, the intolerance, the misogyny and the racism, the widespread fear of people who have any sense of compassion for their fellow humans.”

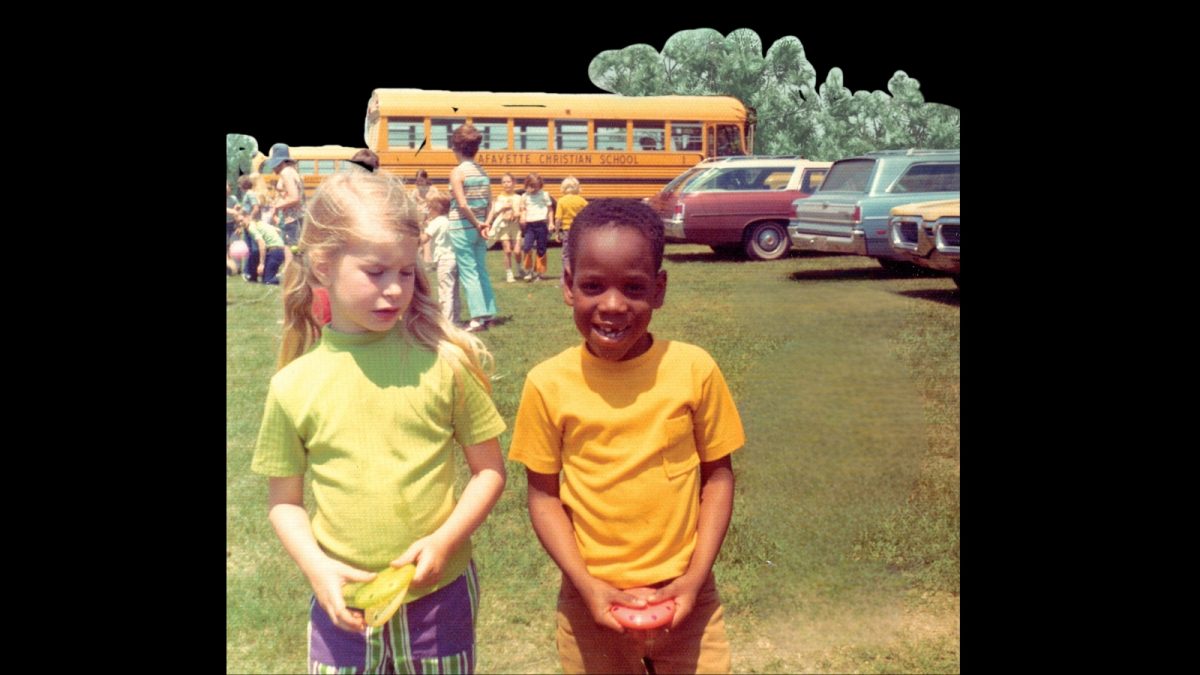

This racialized mistreatment was familiar to Scheeres. “David was adopted when he was two,” Scheeres tells me. “He was three months younger than me, so I witnessed it—what he went through as a Black person in this rural white community—from being the same age sibling in the same class with him. It was very eye-opening, being by his side, just every day witnessing.”

*

When Scheeres published Jesus Land, I understood her story viscerally. Six years after Julia and David left, I was sent to the same institution, also the subject of my forthcoming memoir, Unreformed. When Jesus Land was published, it was lifechanging for me—it came out around the same time the part of me which had been asleep for over a decade woke up, around the time I began reconnecting with peers from what we called “the program.”

Jesus Land helped me recognize the flashbacks I was suffering from as abuse. It helped me grasp how some people who call themselves Christian could also be racist, homophobic, and misogynistic. A sentiment which probably sounds laughable in 2025, but I grew up in the white evangelical church. I spent my formative years in a cult. I didn’t know anything different.

After I read Jesus Land, I connected with Scheeres online. The two of us began coordinating activism against our former school. We, along with the help of many other alumni, and Kidnapped for Christ director Kate Logan (who made a documentary featuring Scheeres about our school), eventually raised enough hell to shut the Dominican Republic campus down.

Scheeres’s work also inspired me to research the troubled teen industry, the hidden arm of America’s prison industrial complex, a largely unregulated network of religious and secular therapeutic boarding schools, wilderness programs, private youth programs, and drug rehabilitation centers. These institutions claim to help teens with problems related to behavior, addiction, eating disorders, and in some cases sexual or gender identity.

It’s important to understand: There is no metric for determining who gets sent to the institutions of the troubled teen industry. If you’re underage, and your parents decide you need to go, you have no recourse.

Over the decades, there have been thousands of allegations of physical, sexual, spiritual, and emotional abuse, in some cases resulting in death, reported at these programs, yet the multi-billion dollar industry remains largely unregulated. In fact, ever since 1979’s showdown at the Christian Alamo, when pastors from across America surrounded Corpus Christi’s People’s Baptist Church in a prayer circle to prevent Texas authorities from investigating claims that young women at the Rebekah Home for Girls were being “beaten with paddles, handcuffed to drain pipes, and locked in isolation cells,” lawyers have litigated faith-based exemptions from oversight of institutions in around 40 states, meaning no one is watching out for kids in religious institutions.

“I don’t think they’ve been exposed to the racism and the hypocritical Christianity that I was exposed to as a kid. They don’t believe it exists, they haven’t read about it, or they don’t want to hear about it.

Looking back, I realize that Jesus Land wasn’t just an indictment of how authoritarianism, racism, and religious extremism control and punish the most vulnerable, particularly children, particularly those who don’t fit into a heteronormative, white Christian mold; Jesus Land was not just an award-winning narrative of trauma. It was, years before the term “exvangelical” entered the lexicon, describing people who left the evangelical church, possibly the first exvangelical memoir.

Which is why it matters that Jesus Land is being made into a movie in 2025. Under the Trump administration, federal support for unregulated faith-based organizations is rapidly accelerating, and claims of religious freedom are being used to undermine civil rights. The prison industry is being rapidly expanded, and people, many of whom are immigrants, are literally being snatched off the street. Child protection standards are being dismantled; Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy is calling for people with mental health conditions, including adolescents, to be sent to labor camps, which he describes as wellness farms.

Jesus Land is not just a story about the past, but a warning of the worst of what could come.

*

“I’ve never seen the religious right like this before,” Scheeres says as we sit cross-legged on the table, batting away mosquitoes. “It’s worse than the Reagan years, the intolerance, the misogyny and the racism, the widespread fear of people who have any sense of compassion for their fellow humans.”

I nod in agreement. Thinking about my dad who, back in pre-internet times, connected with his Christian extremist buddies through mail-order cassette tapes, newsletters, “Christian” conferences, and Focus on the Family radio, I say something about how everything is turbo-charged now—it’s so much easier for extremists of all flavors to communicate through the death boxes we all cart around. As my eyes drift to the cluster of pines behind her, I think about how I, how we, grew up believing in a Jesus who taught us to love one another, the Jesus who loved the poor and sick, the Jesus who literally kicked the sellers and moneylenders out of the temple, how that’s not the Jesus of today. Instead, the head of the Southern Baptist Convention now posits that empathy is an artificial virtue. Instead, in 2024, eight out of ten evangelicals voted for a twice-divorced felon and sexual predator, whose campaign was bankrolled by a drug-addled billionaire.

Julia tells me how all week, parents of the cast members have been coming up to her on set, talking about how Jesus Land, a book most haven’t read, is a relevant story, important to tell, especially now. She tells me how a lot of them are wearing religious sayings, like “Blessed” on their T-shirts, or Bible verses, or little crosses. Their reaction surprises her. “These are white people, right? Most of them are for Trump. My book has riled up a lot of Christians. They’re trying to ban it across the country. It’s so scary now. Coming here [to Mississippi] I was a little on edge.”

She continues, “I don’t think they’ve been exposed to the racism and the hypocritical Christianity that I was exposed to as a kid. They don’t believe it exists, they haven’t read about it, or they don’t want to hear about it. But their kids are acting in this movie. And they’re going to be so surprised.”

I say something, reminding her that not all Christians are like the ones we knew, that there are progressive Christians, ones who are open-minded, and she smiles. “Yeah, this movie is good guidance for how not to be a Christian, right?”

*

The next morning my GPS guides me down Lamey Bridge Road to D’Iberville Middle School, where the Indiana high school scenes of Jesus Land are being filmed. I spot the white and blue sign—with a native American, possibly one of the displaced Biloxi, as its emblem— before the GPS tells me to turn. The school itself is one story and sprawling, the campus denuded of pine trees. It was built in the late 70s, making it the perfect locale for a story set in the 80s.

I nodded, remembering my own childhood, unable to watch the same television shows as other kids, or read the same books, or even wear pants.

I snicker as I spot the sign directing me to “JL” crew parking, thinking how maybe the title Jesus Land would have flown in a blue state, but not in ruby-red Mississippi. As I turn in by what looks like the gym, passing an 80s cop car on a trailer, I park near Scheeres’s rented Mustang convertible. She’d rented it “for Davia,” her 15-year old daughter, she’d told me the night before, but I think it’s the perfect car to drive around in on the Mississippi Gulf Coast during the mild spring evenings, the ocean breeze blowing in.

I walk in the direction of what looks like the cafeteria, passing the wardrobe trailer with its racks of clothing. Scheeres meets me. She’s an extra, a teacher, wearing a tan dress with white geometric shapes and shoulder pads. Her blonde hair is teased. She makes fun of her outfit, but I think she looks incredible with her long limbs and shy smile.

We walk into the cafeteria, “a holding area,” she tells me. It’s lit by rectangular fluorescents. Long rows of tables with attached circular seats are filled with what appear to be teenagers, though later I realize many are in college or even graduates. The small town Indiana cheerleaders, jocks, and hoods sport shoulder pads, their Izod collars turned up, pants rolled into pleats. Many of the boys have mullets; several of the girls have asymmetrical ponytails. “Though no movie ever captures how bad anyone’s hair looked in the 1980s,” I tell Davia, who, like her mom, is an extra, and is sporting her own ponytail.

She looks at me questioning. I explain, “Because we have better hair products now.”

“Can I have my mean girls?” a director calls, and they rise, Davia among them, and exit into the courtyard, headed to where a classroom scene is being filmed on another hall.

Scheeres gestured toward the actor Jared Scott, who plays her ex-boyfriend. His collar is flipped; his hair is styled into a mullet. A few nights before he’d called and asked her about her ex, wanting to know about the character, even what he was like in intimate moments.

Scheeres’s oldest daughter is now in college. The two of us crack up, that this is where Jesus Land has taken her, having this conversation with someone so near her kids’ age.

*

We walk out to the courtyard. Scheeres points out Xavier Jones, who plays her brother, sporting a sweatband, his athletic socks pulled up high, and Ella Anderson, who plays the young version of her. She says she loves their portrayal, but seems relieved to clarify that “neither of them looks like me or David.” She tells me I’d just missed Juliette Lewis, who plays her mom.

We meet writer, director, and former engineer Saila Kariat briefly. She’s a petite woman with brown curls and a wide smile. As we speak, someone pulls her away.

I ask Scheeres how Kariat became connected to the project, and she explains they shared an office at the San Francisco Writer’s Grotto. “She asked if she could read my book, and then she called and asked if she could speak with me. I had a good idea of what she wanted to talk about.”

She’s thrilled that Kariat is the director. “She brings that sensibility, both as a woman and as a person of color, somebody who isn’t from the white evangelical dominant culture.”

She tells me about an early scene, one Kariat wrote, where David is watching a Black family play together on the beach. “He’s in shock, seeing what his life would have been like had he not been adopted, and then Julia—‘I have to speak in the third person,’” she tells me—“goes up and pulls him away.”

“I love that she put that in there,” Scheeres says.

*

“I read it in one and a half days,” Kariat tells me over a call a few weeks later, recounting her first exposure to Jesus Land four years ago, before she’d written “more than twenty drafts” of the script. “I could relate to David on so many levels. I was very sensitive, soft-hearted, like him.”

Kariat’s parents emigrated from a small village in India to Canada. Growing up, she was “the only Indian in my school for my entire childhood. There were no Asians, no Black people. It was all so homogeneous, so I would get singled out all the time. I went to five high schools. That experience [that David and Julia had] of being in a new school, really hit home.”

She also connected with how the Scheeres children, who were raised by Christian fundamentalists, lived outside the norm. “My mom was traditional and had all these rules and restrictions which were so contrary to what everyone else was doing. That’s kind of how [David and Julia] lived too. In a very different way.”

However, when she came to the part where the two were sent to Escuela Caribe, Kariat says, “I was shocked. These places exist and continue to exist even today. They’re unregulated for-profit industries. I’d never heard of such a thing, and that needs to be exposed.”

*

A few days after we both left Mississippi, I call Scheeres. She says being on set was surreal. She tells me about a scene where David and Julia are having their first day at their new high school, where they’re concerned about how they’re going to be received.

“I actually was in that scene,” she says, “One of the teachers holding open the door and welcoming kids back.”

She’s still processing another that took place later, of David and Julia getting off the school bus. Julia sees her friends and runs ahead, ignoring David. She doesn’t want to be the Black kid’s sister.

Her daughter, named after David, plays one of Julia’s new friends.

“It was a moment of tremendous shame for me to even put that in the book,” she says, “But I felt that was who I was at that time. I was tired of the harassment, of being called the ‘N-word lover.’”

I wince imagining how painful the social pressure must have been for them both.

“But my daughter was in that scene,” she continues. “I was in the hallway, listening in on the headphones, and I just had to take the headphones off, and walk away.”

“I wish I could go back,” she tells me. “Part of it is because everything is unresolved. David and I never got a chance to actually talk through everything that happened. He died before we had the opportunity to work it all out. The one thing I’m thankful about the Dominican Republic is that we had that time together, because we became very close there again, because we finally had a common adversary in the administration.”

*

David and Julia had a bond, one that Kariat, the director, celebrates.

“There’s this quote by George Orwell,” Kariat tells me. “From 1984, which is interesting, because that’s the year most of the story takes place: ‘They fear love because it creates a world they can’t control.’”

“David and Julia survived because they had each other. If they’d been alone, they might’ve been broken down, just like all the other characters were broken down. But those two don’t, they stick it out and survive because they have each other. They provide each other’s reality checks.”

As she speaks, I think about how Kariat is describing a phenomenon discussed in Judith Herman’s Trauma and Recovery, based on survivors of Nazi death camps. Political prisoners who were able to form bonds, to become part of what Herman calls a “stable pair,” were more likely to survive.

*

Back home in Georgia, I thought about David and Julia’s bond, and its impact, not just on me, but on other survivors of the troubled teen industry. Because Scheeres loved her brother, and wrote about their bond, so many of us were able to overcome the shame and stigma about what we went through, and begin the long journey of healing. Some of us were even able to join in the wide ranging, at times acrimonious, troubled teen survivor movement, and speak out in support of protections for kids in institutions.

At some point, while we were driving around in Biloxi, I asked Scheeres if it was because of her brother that she was able to write. Something I knew—in the book she wrote about how David’s own writings, in a green spiral-bound notebook, inspired her to write Jesus Land—but I wanted to hear her thoughts now. A pained expression crossed her face.

I later realized—she never really answered.

*

I thought about an actor the two of us ran into as we were leaving the set, Neko Ferro. Like Scheeres, he played a teacher. As the late afternoon sun streamed in through the cafeteria’s windows, Ferro told Scheeres how thrilled he was to meet her. That it wasn’t just that he loved the book, or believed in the project. For him it was personal.

He’d been raised Jehovah’s Witness. “Growing up, there was no creative thought allowed,” he said. “We weren’t even allowed to make up our own songs about God.”

I nodded, remembering my own childhood, unable to watch the same television shows as other kids, or read the same books, or even wear pants. Once, when I was a kid, I’d written my own song—I no longer remember what it was about—and was singing it while I washed dishes. My father began singing a hymn, drowning my voice out.

Scheeres asked Ferro about his family. He said something about how, as an adult, he’d created his own, and we nodded. Both of us are also estranged from our parents, because that’s what religious abuse does—it severs the bond between you and your family.

It was the kind of conversation Scheeres had been having all week. I’d even seen it a few times. But hearing Ferro’s story—his childhood, his separation, his survival—hit differently.

Again, this is why Jesus Land being made into a movie now matters. It’s not just a story about the past. It’s a warning about the dangers of religious extremism, at a time of rising techno-fascism, as the Trump Administration is weaponizing religious liberty. In this political moment, with ICE attacking even pastors, stories like Jesus Land—with its message of how love helps us survive—remind us what we, as humans, are fighting for.