There had been a winter where I had dreamt of the desert almost nightly. I was twenty-nine and something happened to me in late autumn: my mind started looping, my hands shook anytime I left the house. You have a lot of trauma, the therapist I saw told me. I didn’t go back. Another: Have you heard of complex trauma? I hated those afternoons, the train I took to see the doctors, the cure I so desperately wanted and that eluded me. At night I dreamt in violent colors. I dreamt of a different kind of desert: purplish skies and black sand and lanterns. I dreamt of the house in Kuwait where we had left my father. We would wave at each other. I’d wake up crying. That winter, I wept everywhere: on subways, in Italian restaurants, crouching in line at the drugstore. I couldn’t shake loose the image of saying goodbye to my father. Did I cry, I wanted to know. Did I seem scared. Stop asking these questions, my father finally said, softly.

*

For years I didn’t ask my parents for the story of our leaving. I didn’t ask because I thought I knew the story. I lived it, after all. It felt strange to ask for what is already mine. But what is a story that you can’t remember, that colors everything? It’s only when I come to tell it that I realize I’ve never heard it. My mother doesn’t want to tell the story. I don’t want to be in your book, she snaps. Pretend you don’t know my name!

*

I dream of my stomach. I dream of my hands. I dream I am split open, my water breaks, I feel it so acutely it must be true. It is true.

*

Within some Islamic traditions, a dream shouldn’t be repeated aloud. Sometimes, the dream you dream could be meant for another person.

*

I dream of a mouth at my breast.

*

I dream of a daughter being born to me. I dream of a daughter born to another woman.

*

If there is a house in a dream, you are the house. You are its broken windows, its chandeliers or strange carpet, you are the banquet, the doorbell that won’t stop ringing, the music coming from—where is that music coming from. Carl Jung spoke of empty houses in dreams as the representation of the mind that needs to be explored.

*

During the fever-filled nights, I’ve started dreaming again of desert, a bird that speaks my grandmother’s name, “Seham, Seham,” a book I open to find the baby’s name. A name I forget upon waking. I dream of the squeak of packing tape, a room full of moving boxes, the muscle memory of my girl body. I dream of Oklahoma. I dream of a passport with my discarded name, my borrowed name—Holly—and a long drive up a Lebanese mountain to meet a woman who says she can change it. I dream of Alaska. I dream of Saudi Arabia. Places I’ve never been. I dream of Kyoto, my friend telling me the baby is here, I need to hurry. I dream of writing a poem, and I can only remember one line: Reinvention requires departure, an absence to then fill with return. I spend the hours-long dream chanting the line, determined to remember it, because the part of me that is awake, that is aware, knows I will want it later.

The fever breaks. I book a flight to Arizona.

*

I sleep for most of the flight and wake right before landing. The landscape is unfamiliar, flat, ranch-style houses, stretches of red earth. In the taxi, the landscape blurs by: enormous saguaros, flat-roofed buildings, the sky settling into a winter sunset, pale red and magenta. The hotel is sprawling and too expensive, a ranch that was once an all-girls’ prep school, with saguaros standing guard outside the rooms. My balcony overlooks desert. There is a discreet sign in the room warning of snakes. When I take a shower, I try to slow my breathing, calm myself. Even here, even among the rust-colored tiles, the orange blossom shampoo, the steam. It won’t stop. I remember the spine. I say names aloud, her names, against the hot water. I wish I could take my self off like a coat. Just for an hour. Just for an afternoon. I’ll come back, I want to promise.

*

I ask for the story before I travel to Arizona. I am visiting my parents in Connecticut, where they live now. Where they live again. After twenty years—years in Abu Dhabi, in Doha, in Beirut—they returned to America during the pandemic. It is my father who begins talking. He starts with the night before—what they’d eaten, how we’d gone to bed early. We’d all slept in the same bed, even though I’d had my own room, with frilly bedsheets and toys. It was before dawn when the first sound rumbled outside. A thunder that was out of place. A thunder that was not thunder. We all awoke at the same time.

I wish I could take my self off like a coat. Just for an hour. Just for an afternoon. I’ll come back, I want to promise.

My mother interrupts my father, who quips, I thought you didn’t want to talk. She falls into sullen silence, then interrupts again a few minutes later with corrections: It was two days before they went to my grandfather’s house. The invasion was announced on the television, no the radio. The story is derailed by their arguing. They bicker. After her interludes, my father turns back to me and says, grinning, Okay, now back to Scheherazade’s turn.

*

I order a beer my first night in Arizona. It tastes different than the two sips of ruby-red cabernet in California. There is something dangerous about this beer: nobody will know if I drink it or don’t. Nobody cares more than I should care, and I don’t care. The not caring has come upon me suddenly. I am only as accountable as I will myself to be, and I will myself on the balcony of a desert resort, lifting a frosted glass of beer foam to my lips, washing down chipotle shrimp tacos and guacamole.

*

My first night at the resort, I sweat through the sheets, then shiver when I turn the heat down. I dream of my own life, of Johnny: the wine bottle we used as a rolling pin in our first apartment, the bouquet of flowers he bought me in City Hall. The lace of water rolling around our legs in southern France. There had been a time we’d go to bed at the same hour. I couldn’t remember when that had stopped. I dream of our first sheets, maroon red, the canopy net above our first bed. In that first apartment, we kept a jar of sequins on a windowsill. I can’t remember where it came from. Johnny stitched the curtains himself. He’d surprise me with trails of rose petals from the long hallway, red velvet cupcakes and posters of Beirut. I had no idea what I was doing back then, with him, with love, was just a skittish girl with an ugly story. You have a video game heart, my friend Olivia once tells me. You have a heart that keeps regenerating. It’s true. It is the only part of me that is patient and I’d brought it with me: my pulpy, eager heart. All one thousand lives of it.

*

It was just after four thirty in the morning. My father knew this because the first thing he did after the noise, after the non-thunder, was look at the clock. The sound was whooshing, like air being gathered backward. It was the sound of fighter jets. They turned all the lights on. There was nothing on the television yet, no news report. Only an eerie silence outside the windows. He was young when they’d left Palestine; he didn’t know how to place this silence yet, the held breath after a loud sound. He told his daughter to return to sleep, and settled in front of the television. It took thirty minutes, thirty minutes for the monotonous, official tone of the Ministry of Defense to crackle on. (Who is the voice of the Ministry of Defense? he wonders. Is it decided ahead of time? The voice that will clear itself in case of disaster, deep and sturdy enough to hold a nation steady, to contain its panic.) The voice repeated the same line, over and over again: Iraq has invaded the borders in the north. Iraq has invaded the borders in the north. Iraq has invaded the borders in the north. My mother was five months pregnant with my brother, Talal. I had turned four exactly one week earlier.

The fear is something unnameable and bodily. Alone but more alone than alone. Scared but more scared than that.

It was a Thursday, my mother reminded Baba. What does that mean, I ask, but she is looking at him, she is looking past him, she is remembering. Thursday means she didn’t work at the bank that day. It means she was at home with me, and so my father had showered and dressed and left the house alone. He had driven toward the bank where he worked. There was something skittering about the way the cars moved. The Ministry of Defense released another message: the invasion is only in the north. The borders are defended. There is no cause for alarm. He drives through Salmiyeh neighborhood only to find a roadblock, a tank and some soldiers redirecting traffic. The military, he thinks. Of course. Tightened security. A soldier gestures for him to roll his window down and he does. Allah ysa’adak, the man greets him. All men in uniform look the same. But the greeting gave it away. Iraqi.

*

In the Arizona desert I awake afraid. The fear is something unnameable and bodily. Alone but more alone than alone. Scared but more scared than that. It is the first thrust of a plane in the air, the suspension right before something crashes to the ground. No, it was another dream I’d been having: bodies that lean into windows. The spark of their cigarettes. The falling that lasts a long time.

*

Were you scared, I want to know. My father waves these questions away. I couldn’t believe it, he answers instead. The Iraqis were already here. They were in the city center. They had taken over its streets. They were directing traffic. What my father hadn’t known, what most people hadn’t known, was that the small Kuwaiti army had been given their own instructions earlier in the morning: put your weapons down. Dress in civilian clothing. Surrender. Only it wasn’t a surrender as much as a complete reshuffling. The Iraqis were conducting the city by daybreak. It was like the city had already fallen. Like there had never been a time it wasn’t theirs.

__________________________________

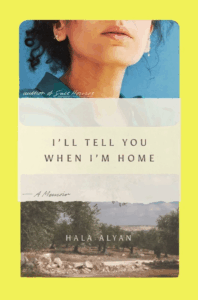

From I’ll Tell You When I’m Home by Hala Alyan. Copyright © 2025. Reprinted by permission of Avid Reader Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.