Feature image © Sarra Fleur Abou-El-Haj.

Article continues after advertisement

There are echoes of Virginia Woolf throughout Honor Jones’ masterful, exquisitely crafted first novel Sleep, which explores the ways in which a childhood trauma haunts her main character, Margaret, and those around her. The novel opens with scenes of families in a summer mode, with descriptions of children at play (“It was damp under the blackberry bush, but Margaret liked it there; she was cozy, like a rabbit,” is the opening line, introducing a scene in which Margaret, at eight, plays flashlight tag). Later, as Margaret, at thirty-five, observes her two young daughters at breakfast in her mother’s kitchen, Jones offers up lines like these: “The light concentrated: first a diluted white. Then cream then suddenly golden. It rose up the doomed cabinets and set the stovetop gleaming. The warmth drew something out of everything it touched, drew it up to the surface—a nectar. That was what shone, not the sunlight—the essence of each object made manifest, the sunlight only circumstance. When the light reached the girls, it gathered in their hair, in their overnight knots, and in the pools of syrup on their plates, giving everything from the child to the dust suspended in air its own nimbus, a haloing she could hardly bear because it was already fading…” At one point Margaret mentions a touchstone book, the copy of To the Lighthouse she read in high school. At another point her boyfriend Duncan lends Margaret a copy of The Waves. One of my first questions for Moore in our email exchange was, How has Woolf influenced on your work?

“I’m so glad you called me out on this!” she responded. “There’s a similar ode to Woolf near the end too. This is embarrassing but at one point I searched the book for ‘light’ and realized I had about 300 references to it shining on various surfaces, 75 percent of which needed to be cut. But yes, I really love To the Lighthouse and The Waves, and I went back to them a lot while writing Sleep.”

She added, “This is a bit of a tangent, but after I finished Sleep, I learned something new about Woolf: that she had been molested by both of her much older half-brothers. It’s such an upsetting detail but what bothered me in some ways even more was how it was both known and yet not known, by which I mean: she wrote about it; it’s in the record and yet you can know a lot about Woolf without ever having heard this. I only learned about it because I happened to pick up the wonderful novel Theory & Practice by Michelle de Kretser, and then went down a bit of a rabbit hole.”

The year she wrote Sleep, Jones was also reading Proust. “So much of In Search of Lost Time (and The Waves) is about waking up in the morning, which is one way of talking about the night. Proust describes that return to the body, then to the mind, then to the world, again and again. I feel like sometimes masterpieces aren’t recommended reading material when you’re trying to write something yourself. But In Search of Lost Time is such a welcoming kind masterpiece. You’ll never ever be able to do what Proust did, obviously, but he does sort of give you permission to go ahead and keep talking about the light spilling over the floor.”

*

Jane Ciabattari: How did this novel begin? What were your first inklings?

Sleep is the place of maximum vulnerability, when you’re floating between knowing and not knowing. As a title, I found it both concrete and mysterious.

Honor Jones: I was thinking about the balance between love and power in a grown child’s relationship with a parent. The first chapter I wrote is about that—the main character and her mother are having an epic and entirely unnecessary argument in a train station. There’s so much history between them, so much anger alongside these glimmers of tenderness.

I was also thinking about the decisions we make as adults, and how many of them are rooted way back in the past. I had written some personal essays on divorce for The Atlantic, and people were asking me to write more—maybe even a divorce memoir. I had no interest in writing a divorce memoir. But it got me thinking about choices, about how and why we make them. I started imagining a novel set around a divorce in which the divorce is the least dramatic part of it.

JC: How did you arrive at the title?

HJ: A lot of the book came out of that liminal moment just before waking when consciousness is unreliable, combined with the image of a child in a bedroom whose door she isn’t allowed to lock. The event that sets the plot in motion happens when the main character is a sleeping child. And then when we return to her again as a woman, she’s watching over her sleeping children. Sleep is the place of maximum vulnerability, when you’re floating between knowing and not knowing. As a title, I found it both concrete and mysterious.

Now the title seems inevitable, but I really struggled with it. Because I have journalism-brain, I kept calling it “the headline,” which I don’t think inspired confidence in anyone. Finally my boyfriend asked me what other titles I liked, and I said The Waves, and he said, “So what are the waves in your book?” As in: What symbolically orders the book? What does it keep coming back to again and again? And I said “sleep.”

JC: We first meet Margaret, your central character, on a late summer evening. She’s hiding in a blackberry bush while playing flashlight tag with her best friend Biddy, Biddy’s brother Danny, and her older brother Neal. In this first section you create a detailed portrait of Margaret’s family—her controlling mother, her low-key father, and Neal, who gets by with transgressions that will haunt her many years after that “bad summer.” How did you write and research these scenes?

HJ: I always worry that I don’t remember as much about my childhood as most people do. I could not tell you a single one of my teachers’ names before high school. But I remember so clearly that feeling of running around in the summer evening. I remember flashlight tag, and I remember that sense of the wonder and confusion of childhood. I loved writing the friendship with Biddy. There’s a lot of my real-life friends in her, though she’s ballsier and blunter than we ever were at that age.

I have my own kids now, and I think a lot about how closely they’re watching me to try to make sense of things. Kids live in a world of rules. If they do X thing they’re not supposed to do, Y thing will happen…but then the world and the adults around them don’t always behave that way.

What happened in that early section needed to be bad enough that Margaret would be affected by it forever. But compared to other people’s traumas, it also had to be relatively quiet. It had to be hard to explain. It had to be something she couldn’t talk about. Margaret isn’t a prodigy—she’s an ordinary kid—but there’s something even then that’s very controlled about her, this sense that she’s got to figure things out for herself, which for better or worse explains a lot about the choices she makes later in the book. But despite how she feels about it at the time, I think what actually happens to Margaret, and her attempts to understand it, will be familiar to a lot of readers.

JC: In your second section, Margaret is newly divorced, co-parenting her two daughters Jo and Helen with her ex-husband Ezra, who is still getting over her decision to leave. And then there is Duncan, the man she is dating. Margaret mulls over the dangers her two young daughters face as she works online as an editor for articles submitted by women who have survived episodes with predators and toxic masculinity. (Harvey Weinstein is part of the news cycle). This theme is front and center in Sleep. How did you go about researching and weaving it into the plot?

HJ: I was an editor in The Times opinion section when the Weinstein story broke (though I was out on maternity leave at the time). I remember being horrified, but at the same time feeling a perverse sense of relief. It’s hard to explain, but the fact that so many women seemed so surprised by the news suggested that the world was a more innocent place than I’d always feared it might be. Lots of women hadn’t met a Weinstein, or someone worse than a Weinstein, yet. I know it was a weird thought, and I don’t think I expressed it to anyone. But a novel turns out to be a good way to explore a weird thought.

When I started writing, I reread some of the incredibly moving pieces from that time. I’ve been an editor for (this feels impossible!) almost 20 years now, and I don’t think I’m as cynical as Margaret is, but she describes something that inevitably happens with a news cycle. The responses to the news become their own mini genre, and the risk is that they start to sound alike and run together. The editor’s job is to find the ones that say something new, but at the same time, Margaret points out, they can’t be so new that readers won’t be able to easily understand and categorize them. One thing that fascinated me about her story is that it resists easy categorization…and I think that’s likely to be common of many forms of transgression or abuse that happen to children. We’re much less tolerant than we used to be of people abusing their power in public spaces, and much more open about it when it happens, but I often wonder how much those shifts have trickled down to private spaces, within families, where power is complicated by love. I think there’s still a lot of silence around that.

Margaret worries about how to tell her kids about Weinstein, and those like him. This is one of the book’s big questions: How do you raise children to be safe without raising them to be frightened? How can you prepare for the worst while still seeing what’s best in people? Elizabeth is such a controlling mother and yet didn’t, Margaret feels, protect her when it really mattered. Margaret is determined not to make the same mistakes, and as a result, of course, she’s primed to make totally different ones—instead of doing too little, she’ll do too much. Ideally parents could wear their vigilance lightly, but it’s really hard to pull that off.

JC: You describe the complexities of parenting after divorce in exquisite detail. How do you do that?

HJ: This is just my life. I’m divorced, and we have three kids under 10. I don’t think there’s anything fundamentally different about being divorced—you’re still raising a family, and raising a family is always complicated and hard and fun and joyful. I’m fascinated to learn how all parents do it, and divide the labor, and remain employed. When we first split up, the logistics seemed impossible to imagine, and it was incredibly helpful to just talk to people who could say: this is how I do it, this is my schedule. It turns out that if you can figure out extracurriculars and doctors’ appointments and summer camps and bedtimes for multiple children, you can definitely, if you need to, figure out shared custody.

One scene I really loved writing in the book is when Margaret meets Ezra’s new girlfriend, and there’s a minor emergency with one of the kids, and everyone is just thrown together to deal with it. I’m interested in the ways parenthood—the chaos and the sheer stakes of it—can mute other forms of drama.

JC: In one scene Margaret and Ezra take their two daughters on a Sunday outing at the Museum of Natural History and she wonders, “Would he make a divorce joke? Did he remember watching that Noah Baumbach movie together?” She recalls telling Ezra she wants a divorce. Their story unfolds, as her new relationship begins. And we follow along as key moments in their family and in her new life emerge, with the backdrop of that “bad summer” and her relationship with her family of origin ticking away beneath the surface. It’s a complex web. What was the most difficult part of getting it right?

HJ: This is probably an annoying answer, but the structure presented itself really naturally. I don’t remember going back and forth much on what went where (with the exception of one memory involving a broken window that I obsessed over for weeks). I knew that I wasn’t interested in depicting the divorce as a plot point, that I only wanted to show Margaret thinking about the divorce as she navigates the aftermath.

It’s funny—I think I felt like I had to mention the Noah Baumbach movie just because so many other people have written about that museum. But it’s sort of irresistible, all those simulacra. I’d completely forgotten this until now, but I actually got this lovely guy at the museum, who’s responsible for maintaining the exhibits there, to talk with me on the phone. For some reason I was under the mistaken impression that the dolphins were suspended in some kind of plastic mold made to look like water, when it turns out (obviously) that what looks like water is only paint and light. He’s the one who told me about the danger of moth infestations—that made it into the book.

JC: Margaret’s memory is the engine of this book, connecting her present, past, and future, her fears and her joys. At what point did you arrive at this process of revealing your story through memory?

I’m interested in the ways parenthood—the chaos and the sheer stakes of it—can mute other forms of drama.

HJ: The big decision was when to tell the story of Margaret’s childhood. Should readers meet her as a woman, and then flash back to the past? Some people, I worried, don’t like reading books from a child’s point of view. Was it weird to begin in a child’s world, and then jump so far into her future? Should her past instead be teased out, mysteriously, for a later reveal?

I toyed with those ideas, but they always seemed wrong to me, sort of dishonest. Margaret questions her own experiences and memories, but I didn’t want the reader to do that—I wanted the story to begin very simply, with what happened. And then the mystery is how she lives with it. So I knew I had to start in childhood, and then I knew that the rest of the book had to begin with Margaret watching over her own sleeping daughters.

JC: How has your work as an editor at the New York Times and now as a senior editor at The Atlantic affected your writing of fiction? Is it an advantage to have editorial skills? A sense of how literary gatekeepers work?

HJ: To begin with the obvious: Yes it has definitely been an advantage! I felt like I knew remarkably little about the fiction world compared to someone who’d done an MFA or worked in book publishing, but I had easy access to lots of people who could advise me, which was an incredible gift. And my colleagues and bosses at The Atlantic have been so supportive and wonderful about the whole thing.

In terms of the actual writing—for sure, being an editor is helpful. On a basic level, editing for a newspaper or magazine teaches you to move things around, and to cut, and to do it quickly. There’s sort of a brutality to editing that I love, at least when I’m subjecting my own writing to it. I think I made very few big structural changes in edits, but inside the sentences, I moved and moved and moved the words. I don’t feel like I’ve really written anything at all until I’ve gone over and over it. Only then does it begin to sound like me.

The one challenge was that I had to really deliberately turn off the journalism voice in me. I’ve been following style guides forever. I tried to break from that where I could, and to let sentences be stranger—to let something be “wrong” if its meaning was clearer that way. I also cut so, so many commas.

JC: What are you working on now/next?

HJ: I’m just finishing a draft of a new book. It’s too soon to say much about it. It’s called Sanctuary, and it’s also about marriage and parenting, among other things, though it’s more of a satire than Sleep and, in some ways, more sinister. I’m really excited about it.

__________________________________

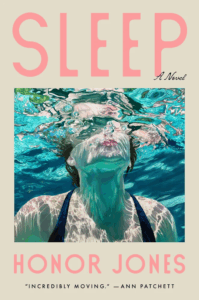

Sleep by Honor Jones is available from Riverhead Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.