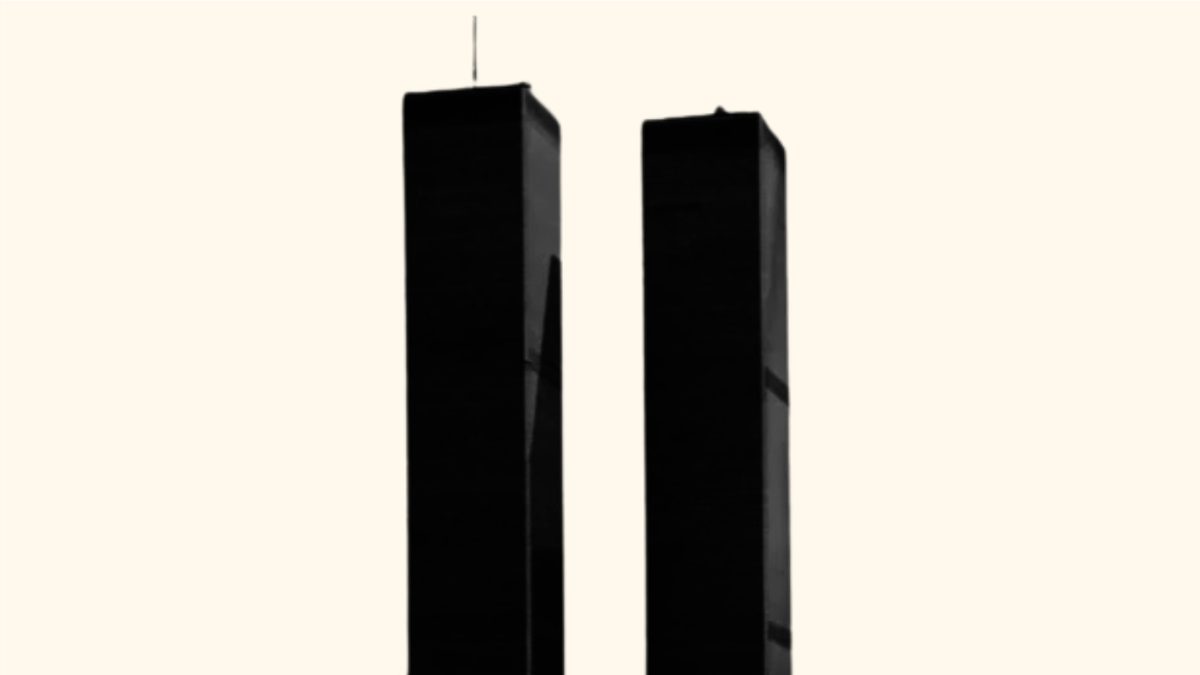

Twenty-four years have passed since the publication of what would become Adam Zagajewski’s most famous poem in the United States. It was “by accident,” he said, that “Try to Praise the Mutilated World” found its way into the last page of a special edition of The New Yorker after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City. Alice Quinn, then the magazine’s poetry editor, had been reviewing an advanced copy of Without End: New and Selected Poems (FSG, 2002), when she was given the request from Editor-in-Chief, David Remnick, to search for a poem that would suitably address the national crisis.

It was telling that Quinn chose a poem composed with no particular occasion in mind. In the years intervening, the poem has remained a lodestar, a contravening presence when, in present day America’s vituperative political landscape, the humanities disciplines and higher education itself has been forced to invoke and defend its own authority. It is the poem’s perturbations, its distinctive mode of inquiry, that remain obdurately relevant. Zagajewski remarked that he wrote the poem with a “philosophical conviction.” The injunction to “praise” survives now with a quieter if no less demanding resonance—one needs to praise, when there’s a need to define, defend, preserve, values that must survive, but threaten to flicker out.

What the poem’s constitutive range of modal verbs exemplify is a mode of poetic questioning. From the interpolation of four variegating imperatives emerges a single prophetic voice. “Try to praise the mutilated world,” it begins. And then, five lines later: “You must praise the mutilated world”; “You should praise the mutilated world”; and finally, “Praise the mutilated world.”

Reading the poem today, one is still struck by the predicaments and responsibilities this voice takes up. The mode is one of willing commendation, trading on the imperative, hortative and jussive moods, the latter two of which have long disappeared from the English tongue. The number and person to whom the poem is speaking—these are themselves in question. The first-person plural arrives two thirds of the way in—and so from what position is the voice issuing its command? Is the poet amongst us, before us, or within?

What Zagajewski had in mind, perhaps, is the encomium, praise as a classical enterprise—the verb alone intimates the mode of speech at the heart of the ancient quarrel between poetry and philosophy itself, tracing back to Plato and before. Just as Plato depicted a Comedian’s and a Tragedian’s praise of eros in the Symposium, a poet has intimated, in the form of verse, how one might resolve two seemingly contradictory tendencies toward persuasion and worship.

One could discern, in the warm reception of Zagajewski’s poetry, that his voice was heard not only as that of a poet, but also as that of an exemplary “moral intelligence.”

Zagajewski describes his poetry both as “a rhetoric of tranquility” and a need to deploy language that holds “the sheen of a certain discovery.” He does not persuade by argument; premises and conclusions are not his medium. The poet titillates, commands by images—and only thus persuades. But this procedure is not so alien to thought as one might think; after all, Aristotle himself said that no one thinks without an image.

There are two classes of images within the poem. There are the earthly ones: “wild strawberries, drops of rosé wine,” “stylish yachts and ships,” whose worldly luxuriance threaten just enough of the opposing forces hidden beneath view. And then there are the ones that intimate deeper images weighted with more serious, religious tendencies, such as “the executioners,” the “gray feather a thrush lost,” and of course, the concluding “gentle light,” brought to the fore in the historical present.

But at the heart of the poem is an image of the “white room” where “the curtain fluttered,” precisely where the second person becomes the first-person plural. “Remember the moments when we were together,” he wrote. Zagajewski’s “white room,” his “fluttering curtain,” is a prime example of what T.S. Eliot would have in mind when he wrote that the best metaphors are ones where it is difficult to say where the metaphorical and the literal meet: a metaphor that “makes available some of that physical source of energy upon which the life of language depends.”

Upon the time of the poem’s publication, four volumes of Zagajewski’s poems had already appeared in the United States, translated by long-time collaborator Clare Cavanagh and brought out by Farrar, Straus &Giroux: Tremor (1985), Canvas (1991), Mysticism for Beginners (1997), Another Beauty (2000). It had been two decades since he left Poland—for love, he reiterates—and at the time, he was teaching at the University of Houston. Four more would follow after Without End (2002): Eternal Enemies (2014), Unseen Hand (2011), Asymmetry (2018), and posthumously, True Life (2023). Already, he was beginning to be understood not only as a legatee of Miłosz, Herbert, Różewicz, Szymborska and Wat, but also of a parallel, more American genealogy.

The American academy has been far more used to a confessionalistic, even solipsistic style in its lyric poetry. Critics often highlight the civic and political concerns that Zagajewski’s withdrawn lyric voice takes up. The political exigencies that faced the American literary public were of a different set. One could discern, in the warm reception of Zagajewski’s poetry, that his voice was heard not only as that of a poet, but also as that of an exemplary “moral intelligence.” His poetry offered a form of consideration; a way to think about American political crises from the perspective of the violence done to language itself; a way, perhaps, to evaluate the fate of its own culture, and its decline.

One of the fundamental threats to (or from) contemporary culture, then, is the absolute suffocation and depletion of inner life, a massification that stupefies and typifies.

Due to the efforts of translator and critic Clare Cavenaugh, it is not just Zagajewski’s poetry that has enjoyed a broader readership in the United States, but also the fine elucidation he offered of his own aesthetic program. In A Defense of Ardor (2005), Zagajewski wrote that poetry “is marked by a disproportion between the high style and the low, between powerful expressions of the inner life and the ceaseless chatter of self-satisfied craftsmen.” One of the fundamental threats to (or from) contemporary culture, then, is the absolute suffocation and depletion of inner life, a massification that stupefies and typifies.

Critics such as Cavanagh and Tess Lewis have long addressed the disparity between Zagajewski’s Polish and American receptions: what some might take to be his gradual evolvement away from direct engagement with political and civic affairs in Poland in fact indicates a growing metaphysical seriousness. This deepening also has an index in the formal features of his poetry—the ambiguity of his pronouns, the firm particularity of his register of images—which teeters between the mundane and the epiphanic, and renders this imbalance itself into view.

For another seven years Zagajewski would continue to teach poetry and philosophy at the University of Chicago’s Committee on Social Thought, where I am a graduate student, and where his name and legacy still lingers, synonymous with a particular pursuit of erudition, a fine sensibility, and, indeed, a boundless ardor. For me, that ardor finds one of its moving expressions in a small poem in Eternal Enemies, my first encounter with Zagajewski’s poetry.

Titled “Epithalamium,” it is as much admonition and prospective consolation as it is praise. “Without silence there would be no music,” it offers—a true theodicy of marriage. Marriage is where “love and time, / eternal enemies, join forces.” The poem under-describes, with quiet abstention, the intractable progression that makes the “years of trial and labor” just as indispensable as the ideal, shadows as much as light. Both come together in the poem’s conclusion, when, says the poet in the historical present, “a great tree with rich greenery grows over us”.

“Cares vanish in it,” he ends.