Queen Mother Audley Moore’s modest Philadelphia home was where some of the country’s most famous Black nationalist leaders, like Malcolm X and members of RAM (Revolutionary Action Movement, a militant youth organization), gathered to study, strategize, and draw inspiration from Moore’s extensive library of revolutionary literature.

Article continues after advertisement

Anyone who passed by 714 North 34th Street in Philadelphia could have mistaken it for a meeting house or a school. Word had gotten around that the home belonged to an elder activist, an old-school Garveyite who had come from the South to educate the city of Brotherly Love’s Black masses. Those who took a quick peek inside the front window saw walls lined with bookcases and young, Black men strewn about in old, thrifted armchairs, their laps piled high with books. Some of them perused pamphlets that surely raised eyebrows: The Communist Manifesto, for one. Others held books with “Negro Liberation by Harry Haywood” printed down their spines. One or two sat on the floor, encircled by newspaper articles, glancing back and forth as if trying to decode a message.

Sometimes the living room was converted from a study to a meeting room, and silence gave way to conversation, spirited debate, and laughter. Activists, ministers, and community members came and went, day and night, their booming voices carrying off into the Philadelphia air. “You want to make revolution in a capitalist country,” Moore would say, “you got to first understand how capitalism works.” She’d shove a book into a young man’s hand on his way out the door with a parting warning: “I want you to get this, I don’t want this to get you.”

Moore’s journey reveals how Black Nationalism emerged not simply as a rejection of American ideals, but as a demand for their true fulfillment.

If there was any place a Black Nationalist could garner support for her cause, it was Philadelphia. Garvey’s UNIA had been particularly popular there in the 1920s. And during the two World Wars, the city was home to the second largest UNIA Division in the nation. Like Moore, many Philadelphians had stayed true to Garvey’s ideals even after the American government deported him in 1927. Others melded into the Nation of Islam (NOI), a religious and nationalist group led by a Georgia-born man named Elijah Muhammad that borrowed both its political principles and its iconography from Garvey. Malcolm X, who had hewed from a family of Garveyites and was now an NOI convert, became the leader of local Temple No. 12 in 1954. His tenure helped further entrench the NOI in the Northern part of Philly.

But the Nation wasn’t the only player in town. Inspired by the wave of youth-led sit-ins and transportation protests, local students soon caught the rebellious spirit, too. When Philadelphia natives, Muhammad Ahmad (Max Stanford) and Wanda Marshall, weren’t out protesting their university’s paternalistic policies, they were reading revolutionary literature at Central State College in Ohio. The more Ahmad and Marshall studied, the more they became convinced that nationalism was the way forward. In the spring of 1962, they joined other students in forming the Revolutionary Action Movement on campus. And when summer break came later that year, Ahmad and Marshall brought the student fight back to their hometown, setting up a RAM chapter in Philadelphia, where Moore was now settling in.

*

“You darling, you are the one I want,” Moore called to Ahmad, pointing at him as he tried to disappear around a corner in her house one day. Although Moore had just moved to the city, her home was already an epicenter of political activism, and other seasoned organizers had invited the student leader to a meeting that day. Ahmad didn’t know much about Moore, but he had heard she was a communist—someone to be feared for a young man who came of age during the Red Scare. So he decided that he would just stand in the back and scope out the scene. Get in and get out.

But Moore had heard of Ahmad, too—especially his work organizing the city’s Black working-class. And so, when she noticed the young wallflower, she tried to corner him. It scared the “living daylights” out of him, and Ahmad made for the door. Moore caught him on his way out. “If you ever want to come by,” she told him as his eyes darted nervously from side to side, “the front window of my study is open, just raise it and come on in.”

A few weeks later, the young organizer was making his way through the West Side when he happened to pass by Moore’s house again. This time, his curiosity got the best of him. Ahmad cautiously approached the home, climbed up the porch steps, and jiggled the front window. It was open, just as Moore had promised. He stilled and listened for voices. Nothing. He climbed into her first-floor study, and there before him was a world of rare books, newspaper clippings, pamphlets, and flyers, all gathered from Moore’s decades of work. Ahmad could see Moore was knowledgeable…even if she was Red.

“Oh, what do we have here,” Moore asked when she found Ahmad ensconced in papers in her office. He had been in the study for an hour or two before she had found him. “Take your time, I’m going upstairs to fix us something to eat,” Moore told him. When dinner was ready, Ahmad joined Moore, and she began to share her insights from decades of Black Nationalist struggle over her favorite southern foods.

Ahmad spent the next few days in deep discussion with Moore about everything from communist class politics to nationalist teachings. He soon realized Moore “made more sense” than “anyone in life.” At the next RAM meeting, he assured the other members that Moore was safe—she wasn’t a threat, and she was an invaluable organizing resource. The group agreed: they would ask Moore to be RAM’s political advisor.

Young radicals weren’t the only ones who sought Moore out. She had taken to hosting regular nationalist training sessions in her living room. On any given day, one might walk in to find Thomas Harvey, president of the local Division of the UNIA or even Malcolm X. According to Moore, she first encountered the young nationalist leader at an open-air meeting in Harlem in the late 1950s, where he was leading Harlem’s Temple No. 7. Not since Garvey had she come across a nationalist who could channel their political message in a way that captured the masses so. She made a point to befriend the burgeoning activist that day.

Malcolm kept track of Moore, too. He scribbled down the location of her New Orleans home in his address book after she left New York, lest he find himself in the Big Easy during one of his speaking tours. And now that Moore had come back to the northeast, the pair reunited in her Philadelphia living room from time to time. At this point, Malcolm was no longer an up-and-coming preacher. He was the Elijah Muhammad-appointed representative of the Nation of Islam and the sagacious leader of the Black Nationalist Movement. But he knew he still had much to learn. If anyone walked into her house expecting to hear the Muslim minister speak, they would have been surprised to find that, whenever he shared a space with Moore, Malcolm sat down, shut up, and listened just like everyone else in the room.

Moore was generous with her knowledge, but she also had an agenda. She wanted Malcolm, RAM, and the others she mentored to join her reparations fight. While she was living and organizing in New Orleans, Moore had determined that “somebody had to pay” for the centuries of physical, economic, social, and psychological terror that Black folks had endured in America. She began advocating for reparations in 1957. Since then, Moore had been doing what she could to spread the word about her big push for repayment. But needed a vehicle, an organization that would back her cause and boost her message. The elder activist saw her chance when she got word of the creation of the National Emancipation Proclamation Centennial Observance Committee (NEPCOC), a local group charged with planning city-wide festivities for the hundredth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

When reporters from the Black Press arrived at a church on North Broad Street in January 1962, they expected to find representatives from mainstream Black groups—a handful of representatives from the NAACP, the Black Greek letter fraternities and sororities, and the like. They were stunned when they walked in. Not one civil rights or church group was there. Instead, reporters found Moore and her sisters, Nation of Islam members, and a handful of activists representing smaller Black Nationalist groups. It was clear that NEPCOC events would take on a decidedly different tenor.

By all means, this committee should aim to commemorate the freeing of slaves, Moore acknowledged, once the nationalists had taken over in earnest. But the real, urgent work ahead of them was to redeem the losses slavery had wrought. The group agreed to use the NEPCOC to develop a massive reparations drive, including organizing an elaborate parade in Washington, D.C. to commemorate Emancipation and commissioning a “ship to tour Africa and to arrange for an equal number of Africans to tour the United States.” These events, they told locals and the Black Press, would kick off a national campaign to “mobilize more than 20 million Afro-Americans entitled to 5,000, or more, indemnity payments in the form of reparations for more than 300 years of forced free labor of their foreparents.”

The raucous parades and the tour ships were an obvious callback to Garvey’s UNIA—to the days when he transformed Harlem streets into rivers of Black people marching in unison, black, red, and green flags flapping in the wind and the Black Star Line, Garvey’s audacious attempt to stitch together the scattered fragments of the African Diaspora through a shipping company that would traverse the Atlantic. Moore looked forward to seeing it all come to life. She started by headlining events like the All-Africans’ Freedom Day Celebration and Bazaar. On April 12, 1962, Black men, women, and children packed into Philadelphia’s Times Auditorium and milled about to the low, rhythmic beating of African drums until the lights dimmed and Moore took the stage. The spotlight followed her as she paced from one end to the other, speaking about Black Philadelphians’ “glorious African Heritage” and the systematic obliteration of their culture.

The activists who gathered in Moore’s living room understood what the founders could not: that a lasting and effective nation requires reckoning with difference, not erasing it.

Your “ancestors were sold as commodities, branded like cattle, not only with irons but with the ignominious term ‘negro,’” she spoke. “Germany was forced by the Nuremberg Courts to pay reparations,” and the “United States was forced to pay reparations to Japan.” Surely America should pay Black people for its crimes, too. For many Black Philadelphians, it was the first time they’d ever heard of the concept of reparations. With Moore settled in their city, it wouldn’t be the last.

Six months later, she was aiming to gain more converts to her cause by headlining the NEPCOC conference. Black Americans were at a critical juncture. They were on the tail end of nearly a decade of sustained, high-profile civil rights protests, most of which had angled for an equal seat at the table and a piece of the American pie. And there was talk of a mass March on Washington to boot. The conference was meant to be a kind of gut check. In the great debate between integration and separation, which approach would ultimately bring Black Americans true liberation? For Moore, the answer was clear as day.

“Make no mistake,” she opened at her keynote address, “we stand today at the crossroads of our destiny.” Down one path was the well-worn road of “accommodation,” a path “laden with wrecked hopes, partial victories that change nothing, and ever-recurring frustrations.” Down the other is a “road to national independence and dignity, with freedom to determine our own destiny.” She followed with two poignant questions: “Have we not traveled too long on the old road? Is it not time to change our objectives?”

Moore understood the appeal of the mainstream civil rights movement. She conceded that non-violent resistance—the bus boycotts, the sit-ins, and much more—had “forced the imperialist enemy to retreat” more than once. “We should not scoff at the non-violent resistance movement,” she acknowledged. “But neither should we be deceived by the minor concessions to it by the enemy.” Moore had hit her stride. “We nationalists reject and abhor the turn-the-other cheek philosophy of Rev. Martin Luther King,” as well as “enemy efforts to dictate and shape our program, policies, and tactics.”

“We are a nation within a nation,” Moore concluded, quoting visionaries like Martin Delany and Marcus Garvey, nationalists who had come before her. It was only right to and a national territory in a country developed by our blood and tears and unrequited slave labor” and “reparations for the injuries inflicted upon us by the dominant white nation.”

Even in her sixties, Moore still had it. She could move a crowd to action in mere minutes. Inspired and persuaded, conference goers penned the NEPCOC “Resolution on Reparations” then and there. The one-page document opened with a sobering assessment of the Black experience in America: “African People were forcefully transported from their ancestral home” under brutal conditions, enslaved, and “reduced to chattels and their culture and family life completely destroyed.” Then they made their case for repayment, arguing that Congress had already granted “their right to reparation:” “forty acres of land for each family as partial reparations” after the Civil War.

Moore was thrilled with her newest converts to the cause, even if they questioned her about the logic of her argument. After all, how could a people who abhor the American government, and who deliberately hope to separate from it, demand repayment from it? Ever the pragmatist, Moore had an answer. Petitioning the “oppressor nation…in no way compromises our demand for recognition as an independent and sovereign nation,” she told them, so long as they were using the government’s resources to secure their vision of a separate Black nation.

Younger activists there took it one step further. On the last day of the conference, a handful created the African Descendants Nationalist Independence Partition Party, with the express aim of founding a separate nation on American soil. Moore spent her final moments at the conference guiding one of those activists, Nassir A. Shabazz, a young man from California, as he put forth the resolution to establish a “provisional government” for a “black republic” in the southeastern United States. Reparations would be the seed money for this venture, and it would require no small sum. Shabazz argued the US owed its Black citizens five hundred trillion dollars total, part of which would be repaid in the land across the South that would become this new Black republic. The remaining balance would be paid directly to Black folk once a year. Founders made quick work of building out their organization. They elected officials; established the Black Guards, a paramilitary wing; wrote a national anthem; and founded a Black Nurse Corps not unlike what the UNIA had done before them. They dubbed October 14th as good a day as any other, African Descendants’ Independence Day. It was a fitting tribute to Moore’s decades-long efforts to build a separate Black nation.

*

The same Philadelphia that witnessed the birth of American independence also nurtured competing visions of nationhood—ones that challenged the very foundations of who could claim full citizenship in the republic. Moore’s journey reveals how Black Nationalism emerged not simply as a rejection of American ideals, but as a demand for their true fulfillment. As we approach America’s 250th birthday, Audley Moore’s legacy poses uncomfortable questions about whose nationalism counts, whose vision of America will prevail, and whether this nation can finally reconcile its democratic aspirations with its exclusionary history. The activists who gathered in Moore’s living room understood what the founders could not: that a lasting and effective nation requires reckoning with difference, not erasing it.

__________________________________

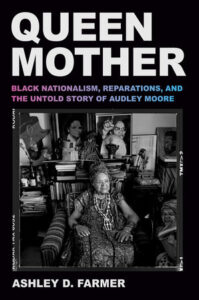

Excerpted from Queen Mother: Black Nationalism, Reparations, and the Untold Story of Audley Moore by Ashley D. Farmer. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Ashley D. Farmer.