Annie Carpenter lies in an unmarked grave just south of a giant blue-and-yellow IKEA, directly off one of the busiest thoroughfares in North America, the Gardiner Expressway, part of the Queen Elizabeth Way, which cuts west and east across the city of Toronto. It feels like an area you drive through to get somewhere else, not a destination.

I have lived in Toronto my entire life, born and raised in this city of immigrants, a city built on the land snatched from the Mississaugas of the Credit by the Toronto Purchase agreement of 1805. The British, looking to secure trade routes and the safety of the growing city of York, as Toronto was then known, entered into a now disputed treaty with the Mississaugas, an Anishinaabe group of families who had made their home here for centuries. The Anishinaabe say they were duped by the British and that the agreement they signed was blank. They said it did not, in fact, cede to the Crown any land, much less the area on which the cities of Toronto and Vaughan are built—their concrete office towers and condos pocking the land with thick, crusty pavement. Our peoples have walked on this land, now trapped beneath the cities’ hard shell of concrete, asphalt and steel, for tens of thousands of years. The soil remembers our footsteps.

I have traveled along this highway too many times to say. Heading in and out of the city. Ferrying my children to Hamilton and back, to see their father’s relations. How many times have I taken this route to get to the airport, or to go to Sherway Gardens, a giant shopping mall smack in industrial west-end Toronto?

All this time, until five weeks before writing this, I did not know that I was driving past my great-great-grandmother’s grave.

How cruel reality is. She was right there. All this time. Since 1937.

Genocide is impossible to retell. The connections between generations are fractured. It leaves us as intimate strangers, looking for the names and faces of those we’ve lost.

Gone from us. From her language. From her Ininiw (Omushkego Cree) family, and so very far away from the water that knew her, the giant Albany River and James Bay basin. Gone from her clothes, her beads and her rocking chair, gone from the sweet smell of burning sage, the softness of a floor of furs and the guttural sounds of a flock of geese making their way south in the brilliant blue sky.

Gone from her children, from the beautiful embrace of a gaggle of grandchildren, my grandmother Margaret among them, who used to listen to her as she sang the sweet sounds of ten thousand generations of our families. We carry our knowledge through our songs. Never written down, our knowledge was lifted and passed from one to the other through our singing, through the beat of a drum. The circular sound of a drumbeat, the sound of a human heart beating.

She used to sing as she rocked.

This is my grandmother’s only memory of her. She said Annie spent hours singing softly and rocking. She did not stop.

Oh, Annie. What happened to you? What did you see? How did you feel when you were sent 1,553 miles from your home, away from everything familiar, away from your way of life, and shoved into—of all horrific places—a “lunatic asylum”? Did you even know what kind of place it was? It must have been disorienting, frightening, as if your world had ended. Were you trapped in a dingy cell? Did you comprehend any of what the whites said to you as they poked and prodded your body, strapped you on a gurney and locked you away? They spoke a language that did not come from you, in sounds that did not come naturally from your lips and that were not understood by your ears. Did they torture you? Hurt you? Did it not matter anymore because this physical pain was nothing compared to what it felt like to be ripped away from your children, your home and family, everything you knew?

We looked for you. Since the 1930s, the decade you were taken away, never to return.

Your grandson, Hank Bowen, my grandmother Margaret’s brother, led the charge, constantly searching for traces of who we were. Do you remember him? He was a loner, a hunter, a lover of the sounds of the bush and the sting of the drink. He nearly died in a Thunder Bay tuberculosis sanatorium, kept hidden away for years as his lungs suffered and heaved from the bacterial infection that ate at his insides. He never settled, never stopped trying to figure out exactly where you were, and who you were. His brown collapsible file folder stuffed with papers, maps, letters and notes was never far from his grasp. Inside were places carefully circled on photocopied maps of all the First Nations, communities nestled deep in the boreal forests and freshwater lakes of northern Ontario stretching from the Manitoba border to Hudson Bay and James Bay. Eabametoong. Lansdowne House. Whitefish Bay. Long Lake 58.

Could she be from here? From these places? Where did her blood come from? His quest was relentless. It consumed him.

The Ontario Hospital, on the shores of Lake Ontario, was the provincial lunatic asylum. Annie Gauthier (née Carpenter) became a patient here in 1930 until her death. (Courtesy of Lakeshore Grounds Interpretive Centre).

The Ontario Hospital, on the shores of Lake Ontario, was the provincial lunatic asylum. Annie Gauthier (née Carpenter) became a patient here in 1930 until her death. (Courtesy of Lakeshore Grounds Interpretive Centre).

*

Every single First Nations, Métis and Inuit family has a story like ours, has lived through a similar trauma. Every single family. Not one was left unscathed by the demonizing policies of the Canadian government and those of the provinces, the British Crown and the Christian churches. Laws were written with the sole intent of crushing First Nations into submission so that the colonizers could easily take the land and everything on it or underneath it.

This is a hard but true reality for Canadians to realize, but it is one that Indigenous Peoples have always known.

*

Annie was five years old when the race-based, genocidal policies of the Indian Act became law in 1876. She was the first of five generations of Anishinaabe and Ininiw women in my family to live under its yoke.

The Indian Act, a paternalistic piece of legislation that remains in effect to this day, was and is a framework for subjugation and control. The government explained the purpose of the act by saying that it rested on the principle “that the aborigines are to be kept in condition of tutelage and treated as wards or children of the State….The true interests of the aborigines and of the State alike require that every effort should be made to aid the Red man in lifting himself out of his condition of tutelage and dependence, and that is clearly our wisdom and our duty, through education and every other means, to prepare him for a higher civilization.”

The government did not refer to “Indian women,” as they were not considered or thought of as persons with rights when the patriarchal act was drawn up. Who was “Indian” was determined only through the male lineage until changes were made, most significantly in 1985, when enfranchisement clauses were removed. Status Indian is the Canadian term used to describe those still governed under the Indian Act of 1876. The act contains a race-based registry, a list of names of those Canada officially recognizes with treaty rights and restrictions.

The newcomers who designed the act assumed they were superior to the Indians because that is what they believed as part of the tenets of Christianity: from the divinity of man flowed power structures and kingdoms. Christianity provided the spiritual foundation of the papal bull known as the Doctrine of Discovery. These newcomers set the table for how British and European arrivals would view the Indigenous Peoples already living on Turtle Island, the continent of North America.

To the settlers, Indians looked different, dressed differently, ate different food and did not live by recognizable European laws or customs. And they did not follow the Christian faith. They might have been living here for tens of thousands of years, but since they did not hold land titles or property deeds familiar to and acceptable to Europeans, the conquerors pushed Indigenous Peoples out of the way. They did not understand we moved around the land, taking care of it before moving again when the land told us it was tired. Indigenous languages come from the land; our way of life, our very being is tied to it. The aki, the earth, is alive. And as such, we never owned it. We held no property deeds or titles. How could you claim ownership over a living entity?

Annie, like all other Indigenous people on Turtle Island, was cast aside by the British ruling class and churches. This was a common practice in British rule, as seen with the Irish tenant farmers, as well as in Great Britain’s dominant involvement in the slave trade. By the late eighteenth century, nearly seventy-eight thousand slaves were being brought to North America every year—primarily on British ships. Merchants were making a killing buying, selling and oppressing people.

Great Britain’s political rules and systems of parliamentary government “othered” populations all over the world to exploit the land and profit all they could for the mother country. The ideals and practices of class and racial superiority that allowed the slave trade to exist—and the British and European “higher” classes to profit from it—came crashing across the Atlantic along with their ships.

The foundations of Canada’s and America’s class and race-based policies of domination—which gave permission to kill both Indian and buffalo, to steal children away from their parents, their language, families and everything they knew—constructed a society that was built to keep us consistently as second-class citizens, governed by a different set of rules and served by a different set of schools and services. The burgeoning caste system in Canada was clearly illustrated by how Annie was treated throughout her life as an Ininiw woman, scraping to survive in a growing country that considered hers a life without value.

The great tool of subjection in Canada was the Indian residential school system, while in the United States, boarding schools played a similar role. The mantra of the schools was: “Kill the Indian, save the child.” This hints at the underlying belief that Indigenous children could be “saved” once they were force-transferred to institutions and turned into something “useful” to the emerging Canada.

The effect was devastating. Destroying and separating generations, the newcomers’ policies and actions left tens of thousands of children, youth, women and men in unmarked graves, buried out of sight and out of conscience. Buried in school grounds with graveyards dug by the students themselves. Buried in hospital grounds, sometimes in mass graves. Buried unceremoniously, anonymously, on forgotten plots of land in fields or city centers, or in church graveyards—not good enough for headstones and, sometimes, buried on the other side of the cemetery fence because, apparently, Jesus Christ did not want to save these particular souls.

None of the residential schools provided Indigenous children with an education sufficient to propel them to university or law school or that would allow them to become doctors. The Indian Act made that illegal anyway: if you went to university, you were no longer counted as an “Indian.” The proof of the plan was in the pudding: residential schools had children work in fields, in laundry rooms, picking apples, building churches, baking bread and digging graves. The children were to grow up and benefit the lives of their masters, to work in kitchens, become domestics, to toil away in the mines and to farm the fields.

Indian women were at the bottom of the social hierarchy. It was not until 1985 that the Indian Act was amended to include women, giving them the same rights as Indian men.

The original purpose of the act and its list of names was not to protect Indians and their rights, but to get rid of them—to reduce their numbers until they were fully assimilated into Canada. Various amendments have been made in an effort to change the law, but it still is a law aimed at annihilation.

If you want to destroy a nation, you destroy the women. That is what the lawmakers, governments, churches and institutions have been complicit in doing through harmful legislation, through policies that made Indian women property and that aided and abetted Indian residential schools. These foundations set the stage for the murder and disappearances of thousands of our children and women. This was the beginning of the murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls crisis we live with today.

This is the background you need to understand in our hunt for Annie.

*

I first heard the term “the Knowing” in Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc, along the Thompson River’s banks in the Interior of B.C. where the Kamloops Indian Residential School was located. Kamloops was once the largest residential school in the area. The surviving children from Kamloops tell stories of being woken up in the middle of the night to dig graves in the apple orchard. They remember their friends that disappeared. For years they told the stories, but few listened, and certainly no lawmakers or governments. They called this knowledge “the Knowing.”

The Knowing provides a different way of seeing.

Every Indigenous family is missing loved ones. Everyone knows of a brother or sister, an aunt or uncle, a friend, grandparent or great-grandparent who has vanished at the schools, at the Indian hospitals or sanatoriums, in lunatic asylums or from the streets. There are entire branches of family trees that are unknown or erased.

My family is made up of pieces of what is left behind. The stories of who we were, where we came from, passed down from generation to generation. We always knew there were others out there—missing. Stories whispered, late at night, among my grandma, my aunties.

Perception is everything.

I am a descendant of both those who have lived on this land for tens of thousands of years and of those who settled it from eastern Europe, of those fleeing oppressive regimes and persecution based on class and racial hierarchy. I write this book informed by the perspective of two separate family trees that have been shaken by two different genocides, the one here on Turtle Island and the other in a part of the world that is still shaking in hatred, a blood feud that has continued for a thousand years.

My father’s family comes from Galicia, a part of southeastern Poland where the borders have shifted countless times and where bombs and bullets still fly. His family fled to New York in 1911 with Austrian passports, on ships ferrying thousands across the ocean. The Talagas were a large mixed family of many branches that I know next to nothing about. But I do know that those with the last name “Talaga” were sent to Nazi concentration camps as laborers, as prisoners. What I do not know is how many of these Talagas I am related to. The Talagas left behind faced unbelievable suffering, some surviving and others dying, in places that are burned into the world’s memory: Dachau. Flossenbürg. Sachsenhausen.

No one in my father’s family spoke of the past. We did not keep in touch with anyone who stayed. Were we part of the Polish resistance or persecuted Catholics? A mixture of both or none of the above? I still cannot answer these questions.

From this worldview—from the legacies of these dual branches of genocide, one on Turtle Island and one far off in eastern Europe—comes my knowing.

*

Uncle Hank’s brown file folder came to me after he died, in the summer of 2011. (I always knew him as Uncle Hank and refer to him that way in this text, but actually, as my grandmother’s brother, Hank was my great-uncle.) My mother brought it over. It had come to her from Hank’s sister, my aunt Connie. She gave it to me with great care. It was as if she were handing me highly confidential state secrets wrapped in a plastic shopping bag. “He’d want you to have this,” she said quietly. The brown folder was heavy, full of letters, inquiries, death certificates and baptism records. They were all the clues we had left of who Hank’s grandmother, Annie, and his mother, Elizabeth, were. Annie was stolen away from us and Liz was silent. Her silence deafened. It told everyone to back off, to not ask questions. What was she hiding, other than who she was?

Time and time again, both the federal Department of Indian Affairs and Ontario’s vital statistics branch had told Hank they had no records for his mother. They told him that so many records had been destroyed and hers were probably gone with them.

How many times have Indigenous people heard this sentence: “The records have been destroyed”?

A 1933 federal government policy led to the destruction of fifteen tons of paper between 1936 and 1944; two hundred thousand Indian Affairs files were destroyed. It is possible these records could have helped in my family’s research. It wasn’t until 1973 that the Department of Indian Affairs agreed to place a moratorium on the destruction of records. But that begs the question: Was the moratorium followed? And what about all the other government ministries and departments that may have held residential school records? What happened to them?

On that first day in Kamloops, I listened to the bang of the drums, and with each beat, my ancestors’ voices got louder: Find Annie.

The bottom line, for us: the Government of Canada and the Province of Ontario declared Liz Gauthier wasn’t an “Indian” because they could find no official piece of paper that said she was.

My uncle Hank would not accept this. He tried to document her. He went in search of those who had known her and her mother Annie. He tracked down, cold-called and visited former neighbors and friends. He interviewed them, asked them to testify that his mother and grandmother were of red skin just like himself. He wrote down their memories. Each swore up and down that Liz was an Indian through and through. In some cases, he even asked them to write letters to the government, sign their names, swear to this truth—affidavits, if you will.

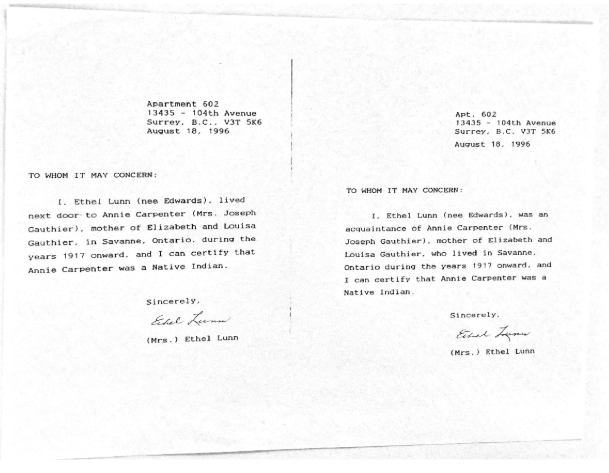

Uncle Hank asked Ethel Lunn, Annie Gauthier’s neighbor, to write a letter to Indian Affairs confirming that Annie was indeed an “Indian.”

Uncle Hank asked Ethel Lunn, Annie Gauthier’s neighbor, to write a letter to Indian Affairs confirming that Annie was indeed an “Indian.”

Why was he so hell-bent on finding her? In part because while Canada told him he was an Indian under the terms of the Indian Act, something he already knew, Canada also had the audacity to tell him he was not Indian enough by excluding his mother. That he, and all his descendants, and the children of his brothers and sisters, could not pass their Indian status down to their children because Liz, their mother, was not an Indian. A bureaucratic decision, baked into the Indian Act’s sexism, along with enfranchisement, combined with incorrect and missing records—the absence of which helped obliterate an entire family’s heritage and sense of belonging. Of knowing who their mothers were, where they came from.

Uncle Hank spent his life looking for Annie. But more importantly, he was looking for himself and for the spirit of his mother Lizzie, a complicated, strong woman. She never spoke of who she was or where she was from, never mind what school she had attended or what she endured while she was there. She took those secrets to her grave. It is as if she hated being an Indian. What happened to Liz that she would want to erase every single trace of herself and, in doing so, refuse to share herself with her own children, leaving them with no knowledge of themselves, cursing generations to blindly walk ahead in the dark?

With Uncle Hank gone, it was up to me, the journalist, to pick up where he left off.

For years I avoided looking through Uncle Hank’s file. It was just too daunting and upsetting. Both Annie’s and Liz’s spirits were completely eviscerated and blown dead away by colonization and the Indian residential school system in Canada. I would pick up that heavy folder, only to put it back down again, overwhelmed by the sadness in the pages, as well as by what seemed to me the nearly insurmountable challenge of trying to figure out why these women—and so many others—were erased.

Canada, as a state, has an obligation under its United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, passed in 2021, to facilitate the finding of the truth, not to impede it. Yet after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission heard from thousands of Survivors and other witnesses who told about the missing and dead children, when the three commissioners, Murray Sinclair, Wilton Littlechild and Marie Wilson, petitioned the federal government for enough funds to start looking for them, Canada refused. Canada refused even though the TRC had identified 3,200 deaths and compiled registers of confirmed deaths of named and unnamed students. The TRC did this independently, with what little resources and records it had; Canada wouldn’t hand over most government records to the commission, citing privacy reasons.

That official list was used to produce a long, flowing red banner containing about 2,800 (known) names of children who died while at school, a banner that is unfurled at events such as the 2022 papal apology at Maskwacis, Alberta, to remind Canada what has happened here. Among the names on that banner are those of five members of my own extended family: Gabriel Carpenter, Charles Carpenter, Thomas Skelliter, Samuel Skelliter and Doris Carpenter.

But those 3,200 children represent only a small fraction of the Indigenous children who disappeared, who died. Finding each child, bringing them home spiritually or physically, is why we hunt. To give them the dignity and respect they were never offered in their brief time on this earth.

We are still searching for their names. On that official list of 3,200 children, the names of just under one-third were not recorded by the government or the schools. For another one-quarter, we don’t know whether they were boys or girls. And for just under one-half of the deaths, no cause of death was recorded. Almost all of the children who died were never sent back home.

What exhausted me about Uncle Hank’s file was that this wasn’t only in my family: we were one family among thousands who had lived the genocide. Inside that folder was information not just about us but about the colonial history of erasure that every other First Nations family faces. The brown folder was heavy with the forces at play that resulted in Annie’s disappearance and those of several of her own children, and the resulting damage it did to the next generation and the next.

Uncle Hank’s brown folder represents what the state did to all of us.

Genocide is impossible to retell. The connections between generations are fractured. It leaves us as intimate strangers, looking for the names and faces of those we’ve lost. And if we find them, we then begin the process of reclamation. There is another choice: the alternative is to just shrug your shoulders and move on. But that is precisely what the architects of genocide want. And I could not do that. The ancestors restless in the back of my mind would not let me.

The day I first felt the meaning of the term “the Knowing” sink in, standing on the grounds of the Kamloops residential school in 2021, after the announcement that nearly two hundred possible grave sites of children had been found, I could not have foretold what the song of those children’s spirits would awaken in me and across all Indigenous Peoples on Turtle Island. That the ancestors within me would respond with such force. On that first day in Kamloops, I listened to the bang of the drums, and with each beat, my ancestors’ voices got louder: Find Annie.

I knew I had to locate her, bring her home. And in that process, I would find myself.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Knowing: How the Oppression of Indigenous Peoples Continues to Echo Today by Tanya Talaga. Copyright © 2025 by Tanya Talaga. Published by Hanover Square Press, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.