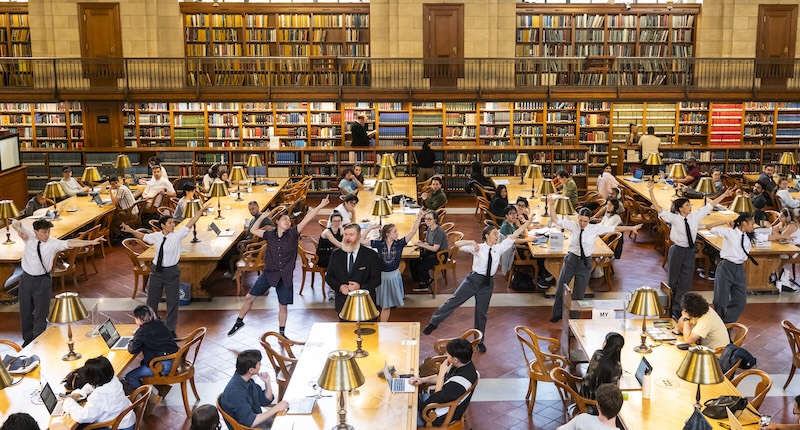

On a Thursday afternoon in May, in the Rose Main Reading Room of the New York Public Library’s main branch, a man suddenly began singing “People,” the 1964 Barbra Streisand standard. Performers dressed as formal library pages in white shirts and black ties emerged from the periphery to dance along. For unsuspecting visitors, it was a jarring violation of the library code of conduct—ingrained in us since childhood, seemingly sacrosanct—that demands silence and stillness.

Article continues after advertisement

For those of us who had signed up for this performance of Lunch Dances, an immersive dance-theater work by the acclaimed team of choreographer Monica Bill Barnes and writer Robbie Saenz de Viteri, the song was a poignant cap to a surprisingly emotional hourlong tour through the library’s large halls and small alcoves.

Naturally, even the uninitiated noticed the singing, even if a few pretended not to. Most were confused, some annoyed, and many began recording the scene on their phones. (To be fair, placards at each table warned of these twice-daily disruptions.)

But disruption was the point of Lunch Dances, the latest project of Monica Bill Barnes & Company, a sui generis enterprise with a mission to bring dance to unexpected places and in conversation with unlikely partners. Some inventive past examples include a popular touring revue with Ira Glass, a disco dance workout through the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and a meditation on loneliness in the public atrium of a Financial District shopping mall.

In each, the combination of spirited movement (by Barnes) and gently confessional text (by Saenz de Viteri) in an uncommon, often rarefied, space reliably produced an unforgettable experience that somehow managed to be both deeply insightful and simply a delight.

Photo credit: Paula Lobo

Photo credit: Paula Lobo

The library’s glorious 1911 Beaux Arts building on Fifth Avenue, while free and open to the public, is physically intimidating—cold in its marble grandeur, confusing in its labyrinthine layout. For the commission, Barnes and Saenz de Viteri sought to penetrate its architectural armor. “What we decided to do with this mission was a direct response to what is unique about being together at the library,” Barnes said when we spoke recently after Lunch Dances concluded its two-week run. In other words, how do humans connect when the rules insist on isolation?

Barnes and Saenz de Viteri were also tasked with incorporating items from the library’s collections of artifacts. Sounds straightforward, except the collections contain over 50 million items acquired over 160 years by generations of curators and include such gems as a Gutenberg Bible, Charlotte Brontë’s writing desk, and the toys that inspired A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh stories. Where to begin?

“I was kind of panicking,” Saenz de Viteri admitted. “I honestly didn’t know how to narrow the amazing ocean [of material] down to some sort of stream.”

He started with one of his literary heroes, Frank O’Hara, who he calls “a profoundly influential writer in my life,” which eventually led Barnes to explore the lives of other poets, such as Donald Hall, Jane Hirschfield and Philip Levine. At first, they focused on published work until library staff steered them to more personal ephemera—gossipy letters, annotated playbills, receipts, requests for teaching sabbaticals, etc. “Both of us fell in love with the smallness of some of the things the library has,” Saenz de Viteri said.

Photo credit: Paula Lobo

Photo credit: Paula Lobo

The staff also nudged them to members of O’Hara’s social and artistic world, including the artist Nell Blaine and the poet Kenneth Koch. Both inspired vignettes in Lunch Dances, which is structured as a string of portraits of fictional characters in private moments of introspection while surrounded by a dancing chorus of those aforementioned library pages, as if they were a kind of embodied catharsis.

“If you know what you’re trying to find,” Saenz de Viteri said, “the library will take over and help you down a road you didn’t even know existed.”

This proved key to unlocking Lunch Dances’ character-driven approach and inspired its title, a nod to O’Hara’s seminal 1964 collection Lunch Poems, which is celebrated for its personal, playful and casually profound approach to what was generally considered a lofty and formal art form—much like how Barnes and Saenz de Viteri engage with, and subvert, concert dance.

And it struck me, after the performance, that O’Hara and particularly Koch are also apt reference points to describe Barnes’ and Saenz de Viteri’s artistic sensibility. Koch has been described as “the funniest serious poet we have” whose “friendly manner” veils “formidable technique.” Similarly, Barnes and Saenz de Viteri’s work appears at first all winky smiles, earnest exuberance and breezy dialogue layered over flailing arms, speedy footwork and spoken self-deprecating asides, often set to a Golden Oldies soundtrack. (Lunch Dances features the Bee Gees and “Rhinestone Cowboy.”)

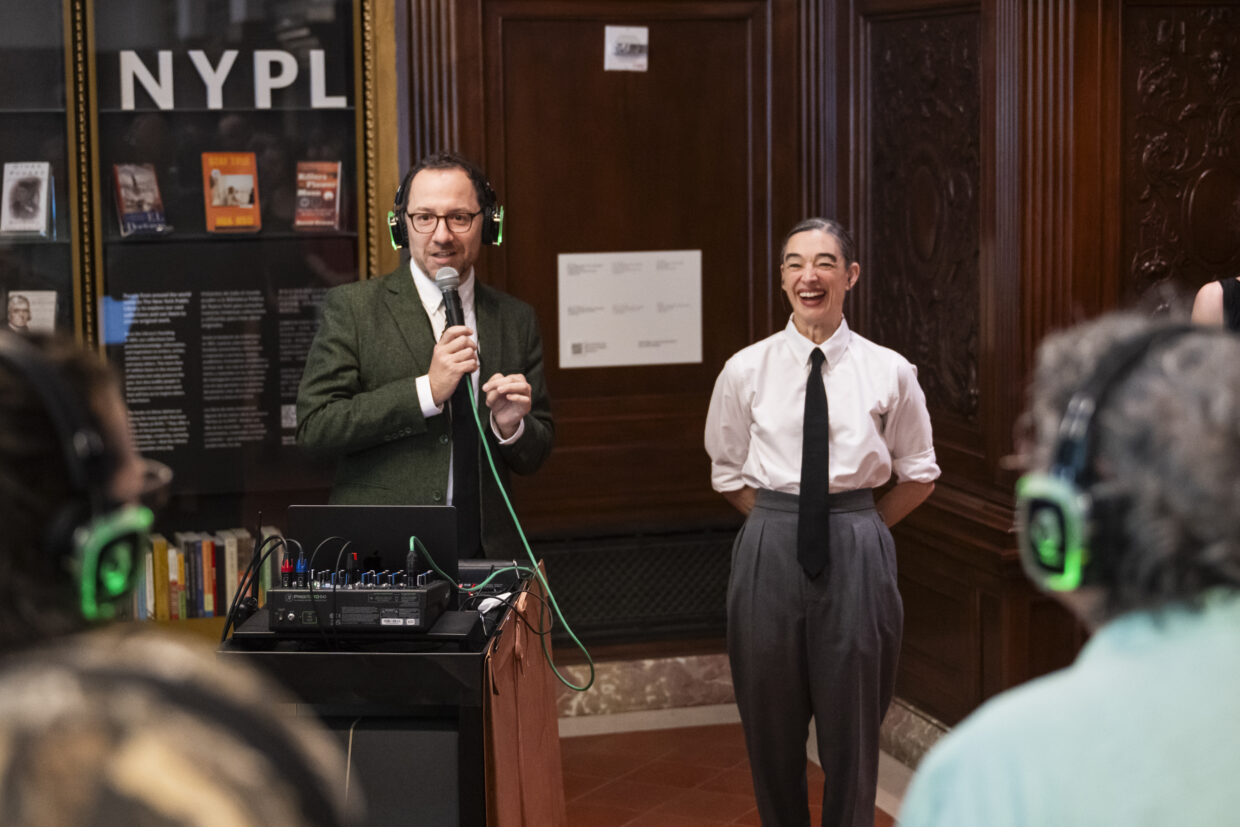

The juxtaposition of Barnes’s charged movement and Saenz de Viteri’s evocative writing—spoken live and delivered via headphones that each audience member was issued upon arrival—enabled Lunch Dances to combine theater’s visceral intimacy with fiction’s narrative flexibility.

Only on closer inspection do you realize that all the tightly choreographed Chaplinesque frenzy and chirpy conversation masks a persistent melancholy and preoccupation with mortality. Case in point: Barnes said that examining the mundane personal collections of the deceased writers gave her “a real awareness of the way your own life is passing” and that what we leave behind is often little more than “these small, everyday communications.”

Leafing through notes, photographs and manuscripts, Barnes also experienced a jolt of nostalgia for the tactual nature of objects. “I think we’re all losing touch with that in a lot of ways, and I think we all feel some sadness towards that,” she said. “I can remember a time when pictures were real things, when letters were real things.” She added, “Maybe more than nostalgia, [I feel] a sense of loss in the fact that we don’t have that anymore.” Such sadness is the stealthy undercurrent of Lunch Dances.

In response, many of the show’s vignettes center around physical objects: Vladimir Nabokov’s drawings of butterflies, a 1961 map of Greenwich Village, a 1956 issue of The Ladder, the first nationally distributed lesbian publication in the United States.

But along with the thrill of foraging and discovery, the solitary experience of wading through so much material over many weeks illuminated the heavy loneliness of research. For Barnes, this fomented “a certain aggression” towards the library. She admitted to feeling “daunted by the physical space” and a need to “thumb my nose at all the marble floors.” Her choreography, for all its evident joy, was born “in reaction to what I can’t do in the library;” it contains “a lot of pent up feeling.”

The juxtaposition of Barnes’s charged movement and Saenz de Viteri’s evocative writing—spoken live and delivered via headphones that each audience member was issued upon arrival—enabled Lunch Dances to combine theater’s visceral intimacy with fiction’s narrative flexibility. The technology, said Saenz de Viteri, “is such a crucial reason the work feels emotional. The only real comparison I can find is like reading a book.”

The headphones allowed Saenz de Viteri to speak to each audience member directly, as a writer speaks to each reader, and alternate points-of-view from omniscient distance one minute to character interiority the next, like a daring novelist. He pointed to “Personism,” O’Hara’s cheeky yet slyly sincere 1959 manifesto to further explain: “The poem doesn’t exist between pages, it exists between people,” Saenz de Viteri said. “And I think the headphones do a similar move of making this thing really feel like it’s just between us.”

Photo credit: Paula Lobo

Photo credit: Paula Lobo

In that sense, Lunch Dances, though outwardly a live performance, is also an intrinsically literary project in its source material, its use of the tools of fiction to create a kind of breathing short-story collection of interlocking chapters, and simply by virtue of taking place in one of the world’s great literary civic institutions.

And for Lunch Dances to find a home in such a place “feels really meaningful right now, in a way that I don’t know that we necessarily could have intended,” Saenz de Viteri said. “We’re all living in this moment of incredible disappointment, frustration and anger at our civic institutions. So the fact that you’re being taken care of and being shown that humanity might exist in this place for an hour, I think that feels like a really important thing right now.”

Both Barnes and Saenz de Viteri have been surprised by the overtly emotional reception of Lunch Dances. There has been frequent weeping. One attendee felt compelled to share that she had recently started a bereavement group. Another, a firefighter, confessed that his work often requires him to forget his feelings but that the show “reminded him to live in those feelings instead.”

Saenz de Viteri struggled to explain such affecting responses but tried: “I think it’s restoring some sense of human connection that a lot of us don’t know how to feel when we come into a building like this,” he said. Somehow Lunch Dances, through its unique alchemy of words, movement and space, “unlocked how emotional this place can be, the emotions it can hold.”