American movie history overflows with stories of drastic alterations, of perversions of intent, of will-o’-the-wisp versions so estranged from their source material that they come across as evocations rather than adaptations. This was especially true in 1930s Hollywood, when sound cinema was still finding its voice, its audience, and its standing amid a society wringing hands over the extent of its power.

Article continues after advertisement

After her failed Hollywood outing at the beginning of the decade, Lillian Hellman had come back with a Broadway smash under her belt, and there’s nothing that town likes more than a hit. She said in 1935, “The most interesting part of my trip to Hollywood is that that I’m going back to take a job at just thirty times what the movies paid me the last time I worked for them.” By January 1936 she had signed a three-year contract with the producer Samuel Goldwyn for the impressive salary of $2,500 a week, stipulating that she had to produce two scripts a year. For her second big project, she was tasked with adapting a wildly successful Broadway play—her own. Translating her stage hit to the screen promised to be a rewarding challenge. There was a significant catch: She would have to change everything about it. Even the title.

It would have been pure disillusionment for a starry-eyed dreamer. It was a good thing that Hellman, now twenty-nine, was already disabused of illusion. A pragmatist whose time in Hollywood was always more about curiosity than indulging in fantasy, Hellman remained fascinated to see how the factory made the sausage, and how she might squeeze some of it herself.

The newfound state of Hollywood as a willing participant in its own strict regulations was a great irony as well, one of epochal proportions.

Hellman’s undertaking was laborious, to make something unrecognizable out of her own work that at the same time recreated the exciting, lacerating drama it provoked. The story of two schoolteachers accused by a malicious, vengeful student of carrying on a lesbian affair would seem to be impossible even in outline: any inference of such a relationship was strictly verboten under the newly enforced Motion Picture Production Code. Then there was the climactic revelation of Martha’s romantic feelings for Karen, the tear-soaked admittance that led to that tragic denouement. That ending—and the entire premise—would have to go.

The first question would rightly be: why? Why would a studio bother spending money on the rights to a property already dogged by scandal? Anyone with even a basic understanding of the movie industry of the 1930s, let alone a Hollywood mogul, would know the difficulty of adapting it to the screen with any semblance of fidelity. And the amount spent was substantial. The producer Samuel Goldwyn, a veteran Hollywood figure known for both his pugnacity and a glorified, almost self-parodic obtuseness, paid $50,000 ($1.5 million when translated for inflation) for the film rights to Hellman’s play.

It was the considerable name recognition of The Children’s Hour, as well as Hellman’s persuasion, that encouraged Goldwyn to purchase it—ironic since its title would be altered to avoid name recognition. Goldwyn’s professional relationship with Hellman was the other major factor in his decision to jump at the property: the two had just finished working on the prestigious 1935 melodrama The Dark Angel, a box office hit that had earned two Oscar nominations. Hellman shared with Goldwyn a fighting spirit, a Jewish background, and an allergy to wish-wash. She was quickly rising to the top of the ranks to become Goldwyn’s favorite.

A titanic personality who stood out even amid Hollywood’s sea of outsized egos, Goldwyn (born Szmuel Gelbfisz in Warsaw’s Jewish ghetto in 1882, renamed Samuel Goldfish when he emigrated to America in 1899) had been a major industry player ever since he formed his self-named studio in 1916. He had a reputation for being more devoted to writers than to stars, giving Samuel Goldwyn Pictures Corporation a literary air rather than one of modish frivolity—an anomaly and an increasing liability in an industry that would be ever more devoted to the box office bottom line. In 1919, Goldwyn had even created a production unit called Eminent Authors, Inc., which allowed famous writers to adapt their own works to the screen for a good salary and guaranteed top billing. The pursuit failed, but Goldwyn’s focus on writers marks a fascinating footnote that contrasts sharply with the famously sour, combative relationship with screenwriters that Hollywood producers would mythically boast throughout the coming decades. Goldwyn continued to crave the skills of savvy, street-smart writers like Hellman, the kind of intellect who might elevate an industry many cultured people still looked down their nose at.

Hellman had been unimpressed with Hollywood upon her first trip to Los Angeles, when she felt like a hanger-on to both her husband Arthur Kober and her lover Dashiell Hammett. She didn’t resent being in California this second time around: while she remained suspicious of the town’s simultaneous fear and envy of East Coast intellectualism, success can change a person. Though some established authors and playwrights from the east considered a Hollywood paycheck a form of selling out, it was work that she’d come to admire. “Writers would talk about themselves as whoring in Hollywood,” she later said. “No, it never occurred to me that such a thing could be true. I was genuinely interested in movies. I genuinely did my best. I didn’t come from the generation that felt any such degradation.”

Hellman’s true feelings about the difference between theater and cinema, though, might be best revealed in a seeming throwaway line in the first scene of The Children’s Hour. “Cinema is a shallow art. It has no…no…fourth dimension.” These words are spoken by Aunt Lily, the self-made theater grand dame. Though she is an entirely unlikable character, and in many ways the play’s unsung villain, a woman whose flighty selfishness leads to Martha and Karen’s downfall, Lily seems to be speaking for Lillian Hellman here. The movies were for stargazing; the theater, for Hellman, was truth, reality, a way to communicate important ideas to receptive audiences who were looking to be jolted awake rather than pampered into dreamland.

Hellman’s eight-year post at Goldwyn would prove richly, surprisingly satisfying for this newly respected luminary of the East Coast intellectual set. She got Hollywood down—the rhythms and cadences of screenwriting but also the status-seeking of a town she once deemed silly. Hellman easily fit in as “one of the boys” at the studio, and her extracurricular hours were devoted to expanding her already vast and impressive social circle, only this time she wasn’t just meeting them through Kober or Hammett. And after The Dark Angel, she had become a necessary right arm to the volatile Goldwyn. That experience, for all its success, had also been Hellman’s first exposure to the strictures of the Motion Picture Production Code, which had recently and quite drastically transformed the movie business, and which made the playwright’s recent run-ins with the morality police back in the New York theater world seem loosey-goosey by comparison.

*

It’s noteworthy, even a little humorous, that Hellman, an outspoken arbiter of independent thought who had little time for the closed-minded, was becoming a part of Hollywood at the very moment that the industry had begun officially submitting to a puritanical code of ethics. The newfound state of Hollywood as a willing participant in its own strict regulations was a great irony as well, one of epochal proportions: a town built by Jewish entrepreneurs, almost all of them first- or second-generation immigrants from Eastern Europe, was suddenly at the mercy of a profound, censorious Catholicism.

To fully understand where the film industry’s newly formalized moral rigidity had come from—and why it would last for the next thirty years, forever altering how Golden Age of Hollywood movies would be made and perceived, and how multitudes of Americans would see not just movies but also the off-screen world around them—one must travel back to the early 1920s. This is when Hollywood was living through the growing pains of becoming the culture-leveling entity we think we know and understand from countless hagiographic history books, talking head interviews, and misty-lensed documentary clip reels: a factory slowly building into an entertainment empire, run by both bottom-line-obsessed moneymen and a growing contingent of artistically motivated craftsmen. This is the birth of the split personality that would forever define American cinema, an industry that always made art and commerce strange bedfellows, triggering debates that rage to this day about the meaning (or the possibility) of film art.

In the early twentieth century, however, Hollywood already had a much less philosophical identity crisis on its hands. By the twenties, there had been a consumerist uptick in the United States, and with the First World War in the rearview mirror, affluent and middle-class Americans were spending their hard-earned dollars on radios, cars, and newfangled kitchen appliances that promised to make their lives easier and more enjoyable. In Los Angeles, the boom translated to an influx of new workers who had moved west, seduced by the lure of movies as much as the location’s oil fields and automobile manufacturers, and the city saw its population double between 1920 and 1925.

Hollywood would eventually become a city within that city, made up of a series of villages (studios) founded by Jews of Eastern European birth or descent like Carl Laemmle, William Fox, Adolph Zukor, Jesse Lasky, Louis B. Mayer, and Jack and Harry Warner, émigrés or their first-generation offspring whose desire to fully assimilate into the gentile mainstream resulted in the mass entertainment of, respectively, Universal Pictures, the Fox Film Corporation (later Twentieth Century-Fox), Famous Players-Lasky Film Company (later Paramount Pictures), Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and Warner Bros. However, by the early twenties, the wholesome images they put on screens were frequently undercut by stories of real-life scandals and off-set licentiousness. Thanks to an incessant stream of sensational newspaper articles and a nonstop rumor mill, the public had the idea of Hollywood as a lair of iniquity and debasement. The movies would soon be a target for moralizers already suspicious of a medium that was proving to exert significant power over audiences hungry for cheap attractions.

When discussing the evils and misdeeds of Hollywood stars of this era, the sad case of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle and Virginia Rappe is frequently referred to as the original sin. A hotel worker turned vaudevillian, the rotund yet balletically graceful comedy star had become such a popular comedic figure of the silent film industry that in 1921 Paramount offered him an unheard-of $3 million, three-year contract. Over Labor Day weekend of that year, Arbuckle threw a lavish party at the St. Francis Hotel to celebrate his new contract; this turned into a multiple-day binge fueled by bootleg booze. The twenty-six-year-old Rappe, an aspiring actress who was among the guests invited to Arbuckle’s twelfth-floor suite, was heard screaming in pain from his bedroom. Examined and sent home by a hotel doctor, Rappe died three days later in the hospital of complications from a punctured bladder. A friend and companion told authorities Arbuckle had raped her, leading to her fatal injuries.

Arbuckle denied the charges, yet the case captured the public’s imagination, and he quickly became a symbol of Hollywood’s wanton villainy. The highly covered trial lasted from November 1921 to April 1922; following two hung juries, a third trial found Arbuckle not guilty and he was set free. The damage to the comedian’s reputation ended his career, though, and the overall perception of the industry took a hit as well. Variety’s headline about the case in September 1921 indicated the widespread belief that this wasn’t merely a “Fatty” problem: WORLDWIDE CONDEMNATION OF PICTURES AS AFTERMATH OF ARBUCKLE AFFAIR, MUST RID FILMS OF DOPESTERS, DEGENERATES, AND PARASITES—CLEANLINESS IN PRODUCING AND ACTING RANKS WILL BE REFLECTED ON SCREENS—CHURCHES AGITATING AGAINST PICTURES.

The article’s positioning of the scandal as the final straw of a perceived wider social problem was a sign of things to come: Hollywood’s most vehement detractors began denouncing the town as a veritable Sodom and Gomorrah. The tragic stories were piling up with sensational swiftness. There were the high-profile suicides of Selznick Pictures’s twenty-five-year-old movie star Olive Thomas and the twenty-two-year-old Famous Players-Lasky screenwriter Zelda Crosby. In 1922, the papers pored over the details of filmmaker William Desmond Taylor’s shooting murder—still a cold case, though at the time Mabel Normand, an actress, filmmaker, and frequent Charlie Chaplin co-star, was implicated in the scandal. Two years later, another Normand scandal erupted when her chauffeur used her pistol to shoot and wound the oil tycoon Courtland Dines.

In 1923, the handsome thirty-one-year-old movie star Wallace Reid died from morphine and alcohol addiction. Some studios responded to this litany of disgraces by making public shows of righteousness, as when Universal added a “morality clause” to its contracts with all new and established stars. Of course, there was no way to enforce these clauses aside from a hand slap or a tsk-tsk; the “Babylon” of Hollywood was its own, enclosed world, and to an increasing number of self-created good-soul Catholics aghast at what they saw, a godless one headed for a reckoning.

The accumulation of these events lit the fuse that would eventually lead to the explosive censoring of the American movie industry, though it was a slow and sometimes painful process. Soon after the end of the Arbuckle affair, 1922 saw the formation of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, established by Will Hays, a lawyer from Indiana who had risen to become the former postmaster general under President Harding. The MPPDA operated under the assumption of cooperative self-regulation from the studios, “to foster the common interests of those engaged in the motion picture industry by establishing and maintaining the highest possible moral and artistic standards of motion picture production.”

Four years would pass before the group started putting pen to paper: in 1926, Hays established the Studio Relations Committee, a group absorbed into the MPPDA, and with his associates made a list of “Do’s and Don’ts” (the latter encompassing eleven things that could not be shown on-screen, including miscegenation, white slavery, and “sexual perversion”) and “Be Carefuls” (twenty-six “dangerous” subjects, which included murder, rape, arson, and excessive kissing). This inventory of forbidden content was devised as a series of strong suggestions, yet these would ultimately be the building blocks for the enforced changes that altered the industry in the mid-1930s.

From this conversation among a group of Catholic laymen in Chicago, only one of whom had ever set foot in Hollywood, the Code was effectively born.

While Hollywood was doing its best to evade or outright ignore the mostly wishy-washy efforts of the MPPDA to regulate throughout the 1920s, a figure was rising in the Midwest who would change all that. Joseph Ignatius Breen’s name might not be as well known as the famed producers, directors, and stars whose names grace film credit lists, but he would be one of the most powerful and feared men in Hollywood history.

Born in Philadelphia in October 1888, Breen shuttled between jobs in public relations, newspaper journalism, and the U.S. consular service, yet the connecting thread was always his deep, proud, stern Irish Catholicism. His relationship to powerful members of the Catholic community had begun in his Jesuit alma mater, St. Joseph’s College, and continued through his work facilitating access of European Catholics to America for the Bureau of Immigration, his publicity campaigning for books such as Catholic Builders of the Nation: A Symposium on the Catholic Contribution to the Civilization of the United States, and his editorship and writing at the monthly National Catholic Welfare Council Bulletin—a pulpit from which he denounced anti-Catholic bigotry and Soviet Communism in equal measure.

His associations with these various Catholic institutions landed him a gig in 1925 that would prove a turning point in his career: publicity director for the 28th International Eucharistic Congress. This massive, worldwide gathering of Roman Catholics would take place the following June in Chicago—the nation’s most Catholic city—and Pope Pius XI was set to make a rare appearance. Not only would Breen oversee the mind-boggling commercial and PR logistics of this event—while also working as the PR man for the city’s archbishop—he would end up running the exhibition and publicity campaign for a documentary feature about the event made by the Fox Film Corporation, with copyrights and profits donated to the Catholic Church. After its gala premiere in November 1926, at Jolson’s Fifty-Ninth Street Theatre in New York, with a full orchestra performing the musical score before a sold-out crowd of 1,770 people, the ninety-six-minute movie went on the road, performing especially well in cities with Catholic populations.

Breen’s success was noted by the Catholic clergymen, clerics, politicians, and businessmen with whom he had become tight, but also, crucially, by certain men from Hollywood. Will Hays, like Breen a Catholic, had come to the premiere as a prescreening guest speaker, extolling the film’s ability to convey the awe, beauty, and importance of religion and faith. Through these circumstances, Breen was formally introduced to Hays, and another devout Irish Catholic who would become an integral figure in the history of cinematic regulation: Martin J. Quigley, the editor and publisher of Exhibitors Herald (later known as Motion Picture Herald), as well as the man who had brokered the deal between Fox and the Church to produce the Eucharistic Congress documentary. Breen’s Catholic bona fides were essential to his steady climb up the ladder in this microcosm of American religious (and business) life, but just as important was his ability to get results. Breen was the type of guy you’d want on your side in a meeting: a hearty schmoozer and a savvy diplomat, with a boisterous, barrel-chested personality.

In July 1929, Breen attended a meeting at Loyola University that would change his life. At a special administrative council of Catholic laymen, a Jesuit pastor from Chicago’s South Side named Rev. FitzGeorge Dinneen was in a rage about a movie he had just seen, The Trial of Mary Dugan, starring the future Oscar winner Norma Shearer as a showgirl accused of fatally stabbing her wealthy lover. Dinneen deemed it a work of filth that never should have passed the Chicago Board of Censors and been allowed to contaminate the locals, especially unwitting churchgoers. Quigley, also attending the meeting, nodded in agreement at the film’s outrageousness yet suggested that boycotts, angry letters, and suing Hollywood studios would achieve nothing. The industry had to be taught to properly self-regulate, and while Hays’s MPPDA rules, already three years old, symbolized a start, a stricter set of guidelines was needed. The collection of concerned Catholics kept expanding. They next employed the assistance of a Jesuit priest from St. Louis named Daniel A. Lord. A musician and movie lover, Lord had served as the Catholic on-set adviser for Cecil B. De Mille’s religious Hollywood epic The King of Kings (1927). From this conversation among a group of Catholic laymen in Chicago, only one of whom had ever set foot in Hollywood, the Code was effectively born.

__________________________________

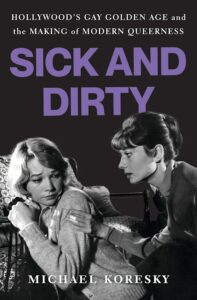

Excerpted from Sick and Dirty: Hollywood’s Gay Golden Age and the Making of Modern Queerness by Michael Koresky. Copyright © 2025 by Michael Koresky. Used with the permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury.