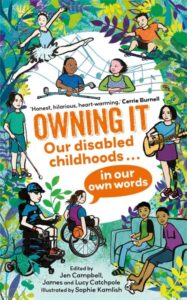

This essay comes from Owning It: Our Disabled Childhoods in Our Own Words, out now from Faber US, the definitive anthology for children on what it’s like to grow up disabled, featuring twenty-two autobiographical stories from the most celebrated writers in the disabled community.

*

Ukraine (Former USSR)

The USSR, the country we live in, is about to fall apart, but no one knows this yet. I am a twelve-year-old deaf boy and outside, in the streets, we are playing War. A three-year-old girl is a nurse. She is saving us under bombardment. But we are surrounded. Eleven wooden rifles are raised and aimed at her. She protects her eyes from the snow with one hand, crosses the porch, goes down three steps, approaches the pavement, and stops in front of the bakery. The wooden gun barrels haven’t lost sight of her for an instant.

“Hello, boys,” she smiles.

In the chestnut branches, my father and I, like two thieves, watch our people’s lips….The truth is, no one yet knows what is about to happen to us.

We do not yet know that the country will fall apart. We do not yet understand what’s about to happen.

Kids are playing War: I watch a four-year-old soldier’s hand tremble as he presses a wooden gun to my three-year-old neighbor’s back. They walk. Whenever someone approaches, the tiny soldier stops.

Kids are playing War: I am putting my hands to the wall and hear a gunshot, two gunshots, an imaginary truck is on imaginary fire. I take my hands off the wall, nothing.

I put my hands back on the wall—four seven-year-old soldiers are on patrol. They have drawn patchy little beards with ink on their jaws. They laugh at each other. Stick out their chests.

We are playing War: our bellies are the drums on which we tap the national anthem. Our fingers are the flags. Across the courtyard, little boys line up along the wall, waiting for war.

*

At first, there is fear. I am a boy walking home from school when a Jewish woman pushes past the crowds of kids coming out of the building and shoves a photograph to my face.

Her lips move, frantically.

“I can’t hear you,” I say.

I point to my ears.

I see her turn to another Jewish-looking kid, then to another.

She asks them a question, but I only see the most exaggerated motions of her face. She turns to another kid nearby.

“Have you seen my daughter?”

She turns away and hurries on, before I can see anything but her question.

We are both stunned and not.

*

Alongside the fear, life around us is going on, as if nothing is happening. On our balcony, in chestnut branches, my father is teaching me how to read lips. We are aiming binoculars at old ladies gossiping on the bench across the yard. Behind them, the children are playing War.

And I just want to watch, a breathless watch: lips of postman, of third-floor housewife, lips munching on gooseberries, lips of boys who are stealing a fistful of currants from an old lady’s bag as she gossips on the bench.

I see the lips of an older girl who counts on her fingers as two other girls kiss: eight, nine, ten, eleven: I am watching how the language taps their cheeks and noses, how they navigate their lips between sounds of dogs yelps and grandmothers’ sneezes, and how behind them they leave the clicks of heels.

I am learning to hear with my eyes.

In the chestnut branches, my father and I, like two thieves, watch our people’s lips.

The truth is, no one yet knows what is about to happen to us.

We do not yet know that the country will fall apart. We do not yet understand what’s about to happen.

*

I am a twelve-year-old deaf boy when a man laughs at me on a public bus when I say that I write poetry.

Impossible! How can anyone deaf even know what poetry is?

At home, I ask my father: What is poetry?

Father does what he always does—he tells a story.

He says, once, a deaf man asked his wife to sit at the piano and play as loudly as possible the entire repository of Chopin. And while she slapped the keys, he dropped onto his hands and knees…and bit into the piano’s wood.

And that…

My father paused. He didn’t have to go on. I understood.

But he went on.

That is poetry.

Most of the stories I hear from my father are about war. Past wars. In his stories, it is 1941. He is shaved so that Germans won’t notice his dark hair, won’t know that he is Jewish. He is learning to dance. The woman—Natalia—who hides my father, hides him for three years, from 1941 to 1944. Not an easy task to keep a restless child inside for three years. Natalia teaches him how to tango.

They dance, for three years of that war, in the room where curtains are always drawn, for three years of occupation, an old woman and a child.

His story stops because I cannot see his lips. He straightens up, and the story continues. That is how it is for a lip-reading boy’s storytelling time.

Once, he escapes outside to play and the German soldiers see him, so he runs to the market and hides behind boxes of tomatoes. (Now, as an adult, and a poet, all my friends tell me there are too many tomatoes in my poems. They say there is too much dancing. Can there ever be too much dancing? I am not sure.)

This is what I know: in the middle of a war—an aged woman and a shaved child tango in a dark apartment.

Then, the war ends and there is no food. Natalia buys a pack of cigarettes, sells them at the train station, one cigarette at a time.

It is February. She walks between wagons, an eight-year-old holding the side of her coat. “Cigarettes,” he yells. “Cigarettes!”

My father bends to tie his shoes, and his story stops because I cannot see his lips. He straightens up, and the story continues. That is how it is for a lip-reading boy’s storytelling time.

*

So, what is poetry?

It is a language of senses and passion.

For me, a poem is a spell.

Not just a spell about an event, but something that becomes an event in and of itself.

Years ago, my father told me a story of a man who, when he couldn’t hear, got down on all fours and bit into a piano leg, so he could hear the music with his teeth.

The language of poetry speaks to all our senses, my father meant to say.

It can speak, privately, to all of us.

It is visceral.

I cannot come back to the past, but a poem’s language can open a room where the past still exists.

And that, I think, is magic.

__________________________________

“Lip-Reading in Odesa” by Ilya Kaminsky appears in Owning It: Our Disabled Childhoods in Our Own Words, edited by James Catchpole, Lucy Catchpole and Jen Campbell. Illustrated by Sophie Kamlish. Copyright © 2025. Available from Faber US, a division of Faber & Faber.