Abortion had been a federal crime in Mexico since 1931, but every state within the country permitted abortion for pregnancies that resulted from rape, and others allowed it if the life of the mother was in danger or in the event of severe fetal anomalies. So when the legislature in Guanajuato, a state in central Mexico, proposed in 2000 to revoke the lone exception to the state’s abortion ban, Verónica “Vero” Cruz thought something along the lines of “Oh hell no.” Eliminating the provision would have resulted in a total ban in a place plagued by sexual violence, and Cruz, a respected activist and the leader of Las Libres, a recently formed feminist collective in Guanajuato, was not about to let the meager sliver of abortion rights that existed in her state shrink any further, or women’s well-being to be used as a political pawn. Something had to be done.

Article continues after advertisement

The proposed reform had come down amid a shakeup of Mexico’s political system. For seventy years, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) had held near-total control through a machine of corruption, cronyism, intimidation, and propaganda, a reign referred to by the Nobel laureate author Mario Vargas Llosa as “the perfect dictatorship” because its autocracy was camouflaged by the appearance of democracy. Following a parade of corruption scandals, pervasive electoral fraud and voter suppression, violence, and economic crises, however, PRI’s stranglehold over Mexican governance had ebbed, and a pro-democracy political faction, led by the National Action Party (PAN), gained strength. PAN was a conservative, anti-abortion party with close ties to the Roman Catholic Church, and in the 2000 election, its presidential candidate, Vicente Fox, campaigned on promises of combatting corruption and democratic reform and won the election in a pivotal victory.

When a woman had an abortion…she was taking a step to assert her human rights and dignity, and that was a radical, and radicalizing, moment.

The mustachioed Fox was originally from Guanajuato and had served as the state’s governor. From the start, he had made his opposition to abortion well known, once stating that abortion should be allowed if the life of the woman or the fetus was at stake, but not for rape survivors because “women who are raped end up wanting and falling in love with their little ones.” Shortly after Fox was elected, the Guanajuato Congress had approved reforms to eliminate the rape exception to the state’s abortion law, an action widely seen as a test of the possibilities of passing comparable legislation nationwide. But if legislators had thought the reforms would sail through without pushback, they quickly realized they were mistaken.

Cruz, a well-connected and indomitable social worker, and a small cohort of feminist compatriots who opposed the legislation, had started convening in cafés and restaurants around Guanajuato’s historic center. Over chicken verde enchiladas at a popular gathering place called El Truco Siete, the group discussed what a feminist activist group that centered abortion could look like in a conservative, Catholic state in a conservative Catholic country where the Church wielded considerable influence. Abortion was stigmatized, but a recent, high-profile case had shown that many people, even those who opposed abortion, believed there should be exceptions, while also illuminating the fact that the legal right to an abortion after rape was not the same as access to it.

On July 31, 1999, a man had broken into a home in Mexicali, the capital city in the Mexican state of Baja California, and entered the bedroom of the resident, a woman named Janet who was asleep with her two children, and Janet’s younger sister, Paulina. Janet woke up to the feeling of a knife on her neck and a man, his face covered by a scarf, demanding that she give him money. After he tied Janet and her children up, he raped Paulina, who was thirteen years old.

When he had left, the family called the police, and Paulina was later taken to a community clinic, where a test revealed she was pregnant. She wanted an abortion, which the doctor said he would provide if granted authorization from the state prosecutor’s office, and they issued an order for the abortion to be performed at Mexicali General Hospital. In early October, Paulina was admitted to the hospital, but administrators disputed, deflected, and delayed the procedure for a week, claiming the family, who had limited means, had to buy medicine to dilate her cervix and that the ultrasound machine was broken. When hospital director Dr. Ismael Ávila Íñiguez intervened, telling the chief obstetrician to follow the authorities’ order, the obstetrician resigned. Then, one after the other, every gynecologist at the hospital refused to perform the procedure as well. Paulina was also visited by two women professing to be state social workers who showed her a graphic anti-abortion film called The Silent Scream (the same film that had supposedly radicalized Randall Terry, the founder of Operation Rescue, in the 1980s), and when they visited the state attorney general to plead for help, he drove Paulina and her mother to a church, where a priest told them abortion was a sin and grounds for excommunication.

When it was clear they still would not change their minds, the attorney general signed a new order for the abortion. Paulina’s surgery was scheduled, but minutes before the appointment, the hospital director told her mother that it came with the risks of sterility and death. Frightened for her daughter’s life, Paulina’s mother did not sign the authorization. “I thought it was better for my daughter to have the baby than to die,” she said. “Probably nothing would happen to her, but if everyone was so angry about the operation, maybe the doctors would do it badly on purpose.” The family returned home and the hospital scheduled a cesarean section for April 14. Paulina would be forced to carry the pregnancy to term and give birth against her will.

Paulina’s plight attracted national, and international, attention and became a rallying cry for activists. It was fresh in people’s minds when, one month after the presidential election in July 2000, PAN representatives in Guanajuato passed the unprecedented amendment making abortion illegal for rape survivors, as well as imposing prison sentences on women and providers. The reaction from abortion rights advocates was fury and apprehension over the broader implications. It was suspected that Fox had directed the introduction of the bill himself, although he insisted it was a local issue in which he had no involvement. “We called on people to not vote for Fox,” Marta Lamas, the director of GIRE (Grupo de Información en Reproducción Elegida), a prominent abortion rights group based in Mexico City, said at the time. “We were afraid of this. Really, we are beginning to see our fears confirmed. What is happening in Guanajuato throws doubt on whether the PAN will really be able to have the type of government Fox has promised.”

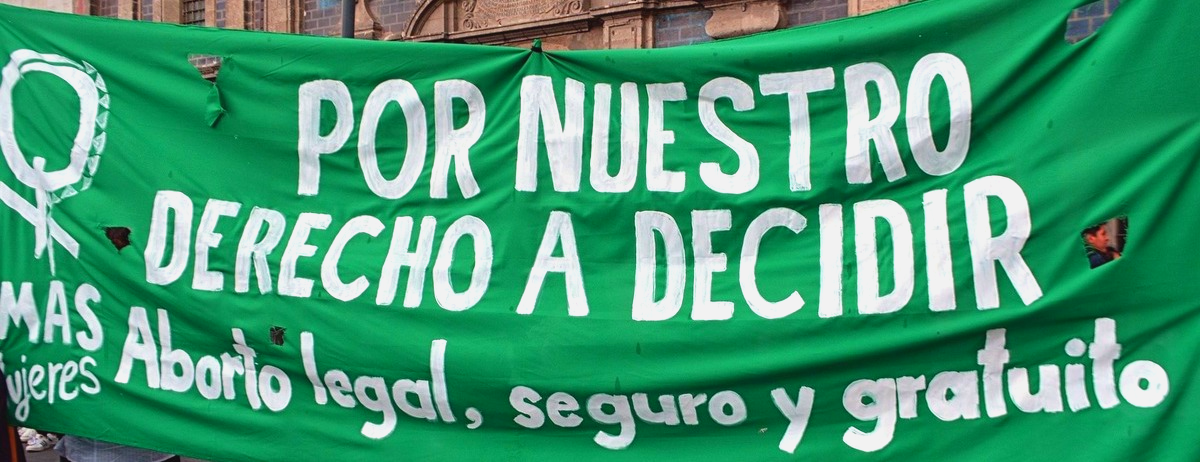

On August 3, 2000, the day the bill was passed, Cruz and her fellow feminist activists in Guanajuato prepared for action. They settled on a name—Las Libres, which meant “the free ones”—and solidified their mission: to fight for legal, free, and safe abortion for everyone, starting with victims of rape. Cruz, who was twenty-nine at the time, coordinated opposition to the law, marshaling resources, sounding the alarm in the media, and organizing large-scale, sustained, and vehement protests in the streets of Guanajuato and Mexico City. Overnight, Las Libres became a force to be reckoned with, and the people in power hadn’t seen them coming.

Scrambling to respond to the outcry, the governor of Guanajuato issued a public opinion poll about abortion, including a question about whether the bill should be returned to the legislature for more study. Sixty-eight percent of respondents agreed. The state government used the feedback as justification for backing down from the bill without admitting that they had misjudged the politics of the situation. On August 29, the governor announced that he was sending the bill back to the state congress for further study, which amounted to a veto. It would not become law. “This is a great day for all women in Mexico and a warning to the PAN,” Cruz said in an interview with The New York Times. “In just a few months, they will hold the office of the presidency, and now it should be clear that they cannot impose their will on the people.”

*

Cruz is a compact woman with an indomitable spirit and a sense of mischief. Her peers routinely describe her as “fearless,” as the hang-ups and anxieties that give other people pause leave her unfazed. Fierce yet warm, she plainly calls out the things she thinks are hypocritical or unjust and carries others along with the strength of her convictions. There are no obstacles, just minor barricades to maneuver around, and she has unerring faith in her ability to prevail. She has never been timid about her work or her belief in its importance and refuses to be cowed into meekness when it is others who are wrong. Like Gomperts, her character combines a strong sense of justice and original thinking with assertiveness and determination. She is a problem-solver and someone who forges ahead with what she believes to be right. If there are consequences, she deals with them, but never lets her decisions be guided by caution or dictated by authority figures. In a documentary about Las Libres, a colleague referred to a sociological experiment where people were put into rooms that were crooked: most people adapted and aligned themselves with the crookedness, but every once in a while, someone walked into the room who saw the crookedness for what it was and pointed out which way was up. Cruz, they said, was that person.

She was born on February 1, 1971, to a large family and grew up in Guanajuato, whose historic center is a charming former silver mining town with colonial architecture and colorful, blocky houses stacked like Legos on the dramatic hillside. Stone tunnels run underneath the city, which brims with theaters, performing arts centers, and lush garden squares. The childhood home of the painter Diego Rivera, and site of the annual Cervantes festival (referred to as “Latin America’s biggest cultural event”), the city draws people from all over the world for theater, dance, music, films, literature, gastronomy, street theater, circus, art, and more. On any given evening, even when the festival is not running, roving musicians in velvet puffed sleeves and breeches perform spontaneous concerts in public squares, calling people to follow them troubadour style as they promenade through, and under, the town.

Cruz was the fourth of her parents’ eight children and willful from a young age. When she was two, she cried because her older siblings were going off to school without her—so much that it led her mother to ask the neighborhood woman who ran a kindergarten if Cruz could start attending early. Even when she was a small child, it seemed unfair to Cruz that it was primarily the girls who had to help with chores around the house, and she chafed against the different expectations for boys and girls and the gendered division of labor. Like her older sisters, she attended an all-girls Catholic school on scholarship, where she was taught by nuns with a strong social conscience. Cruz later thought of them as her first feminist teachers. Their eagerness to engage with their students about issues like poverty and injustice instilled a belief that they could be a force to right wrongs.

Cruz was outgoing and community minded, and in junior high, she and her friends collected in-kind donations from their neighbors and raised money for families in need. She also tagged along with her mother as she participated in a tanda, an informal lending circle in which a group of women contributed a modest amount of money to a pot each week, and each member took turns receiving the collected funds. Visiting the homes of the other women, Cruz heard stories about the hardships in their lives, the violence they suffered or the struggles they faced because they couldn’t read or write. A precocious and compassionate kid, she offered advice and taught some of the women the basics of literacy.

After school, instead of going home, where she had to wash dishes or make beds, she preferred to spend her afternoons with the nuns, who—with no husbands or children to care for and an ability to spend their free time reading, talking, strumming guitars, watching TV, playing volleyball, cooking, and traveling, all with the backdrop of a beautiful convent—seemed blissfully free to her. But then her scholarship ran out and she switched to public school, where, as she put it, “she discovered the existence of boys.” Before long, she didn’t want to become a nun anymore.

Cruz had always aspired to go to college, something her mother had dreamed of for her daughters, and she grew up prizing education. Although her parents did not buy into machismo (the social construct that men must be strong, virile, dominant, and protect the vulnerable, and women are considered weaker and subservient), her father didn’t think it was worthwhile for girls to pursue higher education. His family had scrimped and saved money so his sister could go to college, and when she got married, started a family, and stopped working outside the home, he had felt that the money had gone to waste. Cruz’s mother disagreed; she wanted her daughters to be able to support themselves so that no matter what happened in their lives, they could be independent. That was what Cruz wanted, too, and after graduation, she enrolled in a social work program at the José Cardijn School of Social Work in León, the state’s most populous city, which involved spending extensive time in the field.

After graduating in 1990, Cruz was drawn to working with rural communities, partly because her grandparents owned a ranch and she loved to spend time in the country. She spent four years as a social worker at a community preschool program and in 1994 accepted a job at an organization focused on rural development. Through this work, Cruz noticed that women were dying from cervical cancer at high rates, and that one of the contributing factors was husbands not allowing their wives to get gynecological screenings because they didn’t want male doctors to examine their genitals. Cruz thought education and dialogue could help break down the stigma, and she organized sexual health workshops, which brought another pervasive issue to her attention: teenage pregnancy. At one local school, the teachers needed twenty-five students to hold class, but students were constantly dropping out to have babies. The teachers invited Cruz to teach a class on sexual education and civil rights, but she said one class wasn’t enough—she wanted to devote an entire day to the subject. When she did, the response was overwhelmingly positive and she received more invitations from schools around the state. She knew her workshops were really resonating when she returned to schools and talked with students who joked about how they’d broken up with their loser boyfriends, which she took as a sign that they were considering different futures for themselves and felt empowered to hold off getting pregnant.

It wasn’t just secondary schools that requested Cruz’s services. In one community, Las Cruces, she asked elementary school-aged girls where they wanted to be in five years and they all responded “Salvatierra,” the nearest town with a school. There was no middle school where they lived and it was too expensive for many of them to travel, so Cruz established a scholarship fund to support their education. In a town called La Luz, she taught a seminar on civil rights to first graders, then second, then third, and then the whole student body. Soon after, the mothers, who heard about the workshop from their kids, told the principal they wanted to learn about their rights too. Cruz started teaching them every Tuesday afternoon.

At first when the women gathered, each would say, “My husband is the best,” “He’s so great,” and all the other women in the group would nod along in agreement. But over time, they started to open up and share more honestly about the violence in their homes. A few had attempted to report the abuse to the police, but when they went to the police station, the officers had asked if they’d done something to deserve such treatment. Cruz was appalled by that response and suggested they all march down to the police station together to demand better treatment. The women, emboldened by Cruz’s conviction and their collective energy, agreed, and when they confronted the police officers, they acted differently, solicitously even—“Oh please, ma’am, sit down, tell us what happened.” The women realized there was strength in numbers. When they acted in solidarity, they had power. As for the husbands in the community, they sensed that the dynamics had shifted. If they behaved badly, the women threatened to tell Cruz, which to them was a bigger threat than telling the police.

Around this time, one of Cruz’s friends and colleagues approached her with an opportunity. After the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, which was convened by the United Nations to set strategic objectives and actions for the global advancement of gender equality, the feminist network Millennium had organized workshops and meetings in Mexico City to discuss the issues that had been raised and how to move forward. Cruz’s friend thought she was better fit to participate in the Millennium meetings than she was, and asked if she wanted to be involved. Cruz said yes without a second thought.

The experience proved to be transformative. Abortion was one of the main topics up for discussion, and it was eye-opening to hear it discussed so openly. Growing up, Cruz had overheard women, as they swept the streets and gossiped outside her house, talk about “malas camas,” or “bad beds,” referring to miscarriages, but hadn’t known what they meant. She had also attended a youth church retreat where the religious leaders had spoken dramatically about abortion and everyone (except for Cruz) broke down crying about the “poor babies.” Outside of those vague allusions, abortion had existed in the dark. Now attending the Millennium meetings crystallized her sense of how all the issues they were discussing—gender-based violence, cervical cancer, teenage pregnancy, miscarriage, abortion—intersected, and were underlaid by the question of whether women had agency over their bodies. Invigorated by Millennium’s mission, she became a regional coordinator for the network and later went on to assume the role of national coordinator.

Fighting to expand legal abortion remained one of her key goals, but it was the project of a lifetime, and she knew there were people who could not wait for that hypothetical and distant achievement. Also she was skeptical of a rights-based framework that made access to abortion contingent on a “hollow legal shell” in which the right to an abortion had nothing to do with the ability to obtain one. She was more drawn to direct action and to supporting people in the place where she lived, which would not immediately happen through the political and judicial systems that she saw as fundamentally, intrinsically unjust.

Las Libres was claiming abortion as necessary, as a force for good, as something that would exist no matter what the state did.

As Paulina’s story had demonstrated, even the rape exception that Las Libres had fought to retain was meaningless if someone who had been raped was unable to have an abortion through legal channels. Cruz knew that not every person who had endured sexual assault was willing or able to jump through the necessary hoops to have a legal abortion, involving the police and state’s attorney and hospital administration, or could afford to travel to the US for care or pay for private doctors. At the time, illegal abortion caused the deaths of fifteen hundred women a year in Mexico, and she wanted to figure out a way to help people who had become pregnant from rape to safely end their pregnancies without involving the state and medical authorities in such an intimate decision. She started by searching for doctors in Guanajuato who might be willing to provide abortion care for free, canvassing the city and knocking on the doors of medical offices until she finally found a female gynecologist who agreed to treat Las Libres patients at no charge. The group started spreading the word that they had a way to help rape survivors access safe and discreet abortions among trusted allies around town, including many who had participated in the protests alongside them and professors at the Universidad de Guanajuato, the large university in the historic center of town.

When people reached out to Las Libres for help accessing an abortion, they were almost always nervous and unsure of what to expect. There were a lot of misconceptions, doubts, and myths swimming under the thick sheet of silence, and women were often scared of the procedures and envisioned worst-case scenarios. To help, Cruz accompanied them to their appointments. As the Janes had while running the Service, she stayed in the room to hold patients’ hands, offer comfort, and continue to support them afterward. “The most reassuring thing was knowing they’d be there from beginning to end,” a patient named Fatima recalled. “They wouldn’t leave me hanging. That’s why I always felt safe and never felt scared.”

That year, the gynecologist Las Libres worked with attended an international meeting of OB/GYNs in Europe, where she learned about a drug that could be used to safely and effectively induce an abortion. Cytotec, a brand name for misoprostol, was registered as an ulcer medication and sold in Mexican pharmacies without a prescription; anyone could walk in and buy it. When she returned to Mexico, the doctor took advantage of that knowledge and began offering medication abortions. As Cruz stood in the exam room with patients, listening to the doctor describe how to take the medication and what to expect, it occurred to her that the protocol wasn’t all that complicated. There was no reason why she couldn’t guide women through the process herself or why they couldn’t procure and take the medication outside of a doctor’s office. Cruz shared her idea with the gynecologist, who agreed to try the approach out. For a time, Cruz would let women know about misoprostol—how to procure and take it—and support them through the process while the doctor would provide consultations and follow-up care to those who needed it, such as an ultrasound to confirm gestation or monitoring of heavy bleeding. If the model worked well, they’d keep going.

With that, Las Libres moved abortion out of the clinic and into the community. Although widely available, Cytotec was expensive, costing a few thousand pesos ($200 to $300 USD), but the boxes contained twenty-eight pills each. The misoprostol-only protocol for medication abortion was to take four 200 mcg tablets buccally (dissolved in the cheek), sublingually (under the tongue), or vaginally, and repeat that dosage every three hours, three or four times, until the pregnancy passed. Most people needed twelve to sixteen misoprostol tablets to complete their abortions, so Cruz asked the women who could afford to buy Cytotec to hold on to their extra pills and donate them to women who could not. She also asked them to provide support to other women, informed by their own experiences. Many were terrified by the prospect of taking the medication, unsure how painful it would be and what the physical experience would feel like, if it would work, or if there would be long-term effects. Cruz wanted them to hear from others who had safely navigated the process on what to expect and that they would be okay.

A core pillar of Cruz’s approach was also to combat the shame and stigma that so often surrounded abortion. Seeking an abortion could be an isolating experience without someone to confide in, and with Las Libres, people never had to worry about being alone or judged, because those guiding them had had abortions themselves and were uniquely equipped to offer validation and reassurance that the decision was the right one, without explanation or justification. Society might claim that abortion was wrong, that it was a crime, that it violated religious edicts and came with dire consequences, but Las Libres existed separate from that. When a woman had an abortion, they believed, she was taking a step to assert her human rights and dignity, and that was a radical, and radicalizing, moment. “The women would almost always come back after the abortion and ask, ‘If I was able to have my abortion in a safe and free way, we all ought to be able to do the same,’” Cruz said. “‘What can I do to ensure another woman can have this freedom?’ That was the lightbulb moment. This was the answer. Women would share their experiences. That was vital.” They became links in a chain, paying it forward and breaking down taboos and barriers one at a time.

The formal title for this approach was the modelo integral de acompañamiento para un aborto seguro (MIAAS)—which translates to the “comprehensive support model for safe abortion”—or more commonly and concisely, acompañamiento or “accompaniment.” Although direct action—facilitating self-managed abortions—was at the core, Las Libres had broader aims. In her book Abortion Beyond the Law, sociologist Naomi Braine explained how accompanying someone through a self-managed abortion “enacts a profound disruption of institutional violence resulting from a law and/or a criminalized context”—effectively, the people in the accompaniment networks were subverting and undermining not only the law, but the idea that laws could dictate what someone did with their body in the first place. Las Libres was claiming abortion as necessary, as a force for good, as something that would exist no matter what the state did. Over in Europe, Gomperts was gearing up to make a similar statement with her next boat campaign.

__________________________________

From Access: Inside the Abortion Underground and the Sixty-Year Battle for Reproductive Freedom by Rebecca Grant. Copyright © 2025. Reprinted by permission of Avid Reader Press, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.