Fonseca, Jessica Francis Kane’s transporting new novel, explores the complicated personal life of iconic British author Penelope Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald began publishing fiction at age fifty-eight, and won the 1979 Booker Prize for her third novel Offshore, based on her experience living on a rundown houseboat in London. Her final novel, The Blue Flower, about a romance in the early life of Novalis, was so revered by American critics that that National Book Critics Circle changed their rules for eligibility to include books published in the US. in English by authors from other countries and honored it with the 1997 NBCC fiction award. (Finalists that year were Don DeLillo, Underworld; Charles Frazier, Cold Mountain; Andrei Makine, Dreams of My Russian Summers, and Philip Roth, American Pastoral.)

Kane enters Fitzgerald’s universe seamlessly, combining facts from her life and imagined connections and scenes. She selects a rare slice of life Fitzgerald, whose early novels were autobiographical, didn’t write about except in an essay explaining why she didn’t write about it: her months-long 1952 visit to a silver-mining town in northern Mexico she gives the fictional name Fonseca. “She was thirty-six years old, pregnant with her third child, married to a man who was a brilliant writer and editor, but who had begun to drink too much, too often,” Kane writes. Fitzgerald went to Fonseca as the World Review, the highly respected literary publication she and her husband Desmond co-edited, was flailing financially. Desperate for a way to support their growing family, she was in search of an inheritance after receiving a letter from the Delaney sisters, who indicated their relations in Ireland were gone, and they hoped to meet Valpy and “suggested they might leave him all their money,” Kane writes. Fonseca includes excerpts from Kane’s correspondence with Fitzgerald’s son Valpy, who accompanied her on that trip, and her daughter Tina, who was three at the time of the Mexico trip. The blending is superb.

Photo: Beowulf Sheehan © 2025

*

Jane Ciabattari: What is the origin story for this novel? When did you first learn of Penelope Fitzgerald’s journey to northern Mexico?

Jessica Francis Kane: I had read Hermione Lee’s biography of Penelope Fitzgerald, which mentions the Mexico trip very briefly, but it was not until I read Lucy Scholes’s essay in Granta, “The Peripatetic Penelope,” that something sparked. Scholes did an excellent job of highlighting how difficult and unusual such a trip was, for, as she writes near the beginning of the essay, “a young, pregnant and near-insolvent woman to have made by herself in the early 1950s.”

I guess mostly simply, I took Fitzgerald at her word.

It was the summer of 2017 and I was sitting at my kitchen table and I remember thinking, Wait a minute. What? How is this not more widely known? Scholes wrote, “[Fitzgerald] put her work on hold, left Desmond to take care of the magazine, parked two-year-old Tina with her grandparents, and took six-year-old Valpy with her.” That verb: parked! The whole endeavor sounded so sudden and desperate, I knew I had to look into it.

JC: How did you discover the motivation for her travel? In an Author’s Note you mention Fitzgerald’s 1980 essay “Following the Plot,” about an unwritten story, based on her trip to the north of Mexico. to visit sisters “looking for an heir.” She stops and never writes that story. Why do you think she did that? And what motivated you to carry it forward?

JFK: Scholes mentioned and quoted from the “Following the Plot” essay, so the first thing I did was get my hands on a copy of The Afterlife: Essays and Criticism by Penelope Fitzgerald so I could read the essay in full. I guess mostly simply, I took Fitzgerald at her word. In that essay she says letters had arrived that dangled the possibility of an inheritance, and she decided to make the trip to Mexico to see about it. She and Desmond were quite desperate at that point, living beyond their means in London, editing a failing literary journal, with two young children and a third on the way.

Who knows why she stopped? She says herself in the essay, “I hadn’t the capacity to relate the wide-spreading complications of the Mexico legacy, however well I remembered them.” The open pursuit of money would have been distasteful to her. She came from a very ascetic family: two great-grandfathers were bishops, one uncle was a priest who took a vow of poverty, her father was the editor of Punch, and another uncle was a mathematician who helped crack the Enigma code. These were people who made do.

Another reason she may have stopped is, I think, revealed in a sentence toward the end of the essay, “Everyone has a point to which the mind reverts naturally when it is left on its own.” If the Mexico trip was that point for her, then what happened there that stayed with her all her life but she didn’t later use as material for her novels? This was the key to Fonseca for me.

JC: Did you base your city on Saltillo? And also carry forward Fitzgerald’s fictional city of Fonseca? What does it mean?

JFK: The town Fitzgerald visited was Saltillo, but she never spoke about the Mexico trip after she returned and in the “Following the Plot” essay she refers to it as Fonseca, with no explanation. I suspect it was a rueful name on her part because in Latin “fonseca” means “dry well.” I based my Fonseca on what I could learn (from old guidebooks, maps, history websites) of Saltillo as it was in the 1940s and 50s. It was much smaller then and known as an artistic center.

JC: Penelope’s relationship with her husband, and their correspondence while she is away, is woven into the story throughout Fonseca. She’s frustrated by his lack of a practical side (and his drinking), and still attracted to his intellectual and romantic side. And yet, when a man who claims to be a Delaney shows up, she is drawn to him. Is this fact or fiction?

I eventually asked myself, What kind of novel would you want to read about Penelope Fitzgerald?

JFK: Penelope and Desmond stayed together until his death in 1976. Her first novel The Golden Child was written to entertain him as he declined. Despite all the problems, I think they must have loved each other deeply. “The Delaney” in my novel is fiction, but again, based on tantalizing bits in her “Following the Plot” essay. She writes, “As time went on, more pretenders…arrived, even one who claimed to be a Delaney, and moved into the house.” The possibilities are all there. I just followed the plot!

JC: How did you set the timeline for the novel, from Dia de los Muertos to Candlemas?

JFK: Well, Fitzgerald was an Anglican married to a Catholic. She had an uncle who converted to Catholicism and became a priest and another who was a priest in the Church of England. She came from a religious family and she was religious. In her novels religion is often presented in an intellectual way, but late in life Fitzgerald said in an interview that one of her regrets was that she had not been more forthright in her fiction about her faith. So as a faithful woman and mother visiting a Catholic country over Christmas, I wanted to lean into the holidays and think about how she might have perceived all of it.

JC: You have many intriguing scenes with Edward Hopper and his wife Jo, including Hopper’s request to paint a double portrait of Fitzgerald and Jo. Were the Hoppers in Mexico at the same time she was? Did they meet each other?

JFK: The Hoppers had traveled to Saltillo on painting trips a couple of times by 1952 and were there again the same winter as Fitzgerald. Whether they met is not known, but it seemed within the realm of possibility and a rich one to explore. Fitzgerald was an amateur artist and very knowledgeable about art (she wrote a biography of the pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones). In my story, Hopper doesn’t get his double portrait, but I get a double portrait of two very different artistic marriages.

JC: How did you gather the material to create an authentic sense of Mexico in the 1950s? Fitzgerald’s fiction? Visits? Interviews? Books?

JFK: Twice I had plans to visit; both times foiled by the COVID pandemic. Eventually I leaned into the idea that my Fonseca could be a little bit magical, as it doesn’t really exist, after all—it’s a name Fitzgerald made up. So that gave me confidence. I read old guidebooks, I found an old Baedeker’s, I scoured (and borrowed) from the one short story (“Our Lives are Only Lent to Us”) of Fitzgerald’s that seems to be set in a place like the one she describes in “Following the Plot.”

JC: And the food? The complicated drinks menus and meals served by the Delaney sisters in their salons, which attracted a range of people eager to benefit from their resources?

JFK: More research and the fortuitous discovery of a traditional Mexican cookbook in the kitchen at the Millay Colony when I was there one Wintertide session working on the novel. The universe just sends what you need, I swear.

JC: At various points in the novel you include letters from Fitzgerald’s son Valpy and her daughter Tina. How did these inserts evolve?

JFK: This was the scariest part of the whole process. I had sold the book based on a partial manuscript in the early summer of 2020. I was working well and had told my editor I thought I could be finished in a year! Then that September I got an email from Fitzgerald’s literary executor, her son-in-law Terence Dooley, saying the family was aware of the book and Valpy, especially, was interested in being in touch. I wrote back immediately, explaining how I had come to the project, and I received an encouraging response. Nevertheless, I stopped writing. I was terrified. For the next six months, I emailed with Valpy and Tina, asking them questions about their mother and what they knew or remembered about the Mexico trip, and they were very generous and forthcoming in their responses, but work on the novel had come to a complete halt. However, I loved their emails and I eventually asked myself, What kind of novel would you want to read about Penelope Fitzgerald? The answer was one that included this correspondence from her children, and so I started again. (I would end up starting over four more times!)

JC: What are you working on now/next?

JFK: A collection of short stories and another novel. I can’t say more. I’m very superstitious!

__________________________________

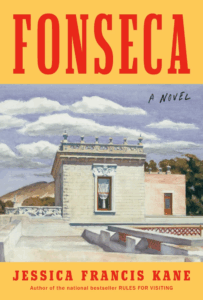

Fonseca by Jessica Francis Kane is available from Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.