“It is starting like this.”

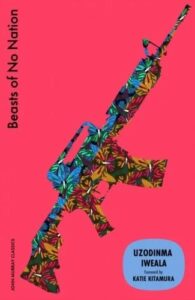

The opening line of Uzodinma Iweala’s Beasts of No Nation is a ferocious one. A sentence of dread and anticipation, but also one of annunciation – the start of the story, which unfolds with ever increasing urgency and momentum from this single sentence. The arrival of a voice, and in that voice, a wholly indelible character.

Agu is the speaker of this sentence, with its dialect-inflected English and its perpetual present tense. I remembered his voice from the first time I read the novel, nearly twenty years ago. More recently, when I picked up the book in anticipation of writing this foreword, I opened it to the first page and there it was again—the voice that I recalled from years ago, one that immediately and intimately established a character, and through that character, an entire world.

The story of Beasts of No Nation is relatively simple. Agu is a young boy whose father has been killed in a brutal civil war in an unidentified West African country, and whose mother and sister have fled. Left behind in his village, Agu is recruited—although “forced” or “coerced” seem like more accurate words—into a band of guerrilla soldiers. Over the course of the novel, Agu undergoes a treacherous coming of age, shedding his former identity as a bookish boy and entering into a manhood marked by extraordinary violence, abuse and horror.

There is never the benefit of hindsight, the reassurance of a given outcome, or anything other than the rapidly fading innocence of a child.

In Agu’s voice, Iweala executes two notoriously difficult technical effects: the child’s point of view and the sustained present tense. And yet it’s difficult to imagine the novel without both. While the arc of Agu’s transformation is tragic and the story of the civil war and its battalions of child soldiers is wide in scope, the power of the novel lies in its immersion. There is no moment when Agu, or the reader, escapes the present tense of the narrative. There is never the benefit of hindsight, the reassurance of a given outcome, or anything other than the rapidly fading innocence of a child.

Armed only with his growing knowledge, Agu ventures into the world of the Commandant, the leader of the guerilla battalion. The Commandant is a monstrously charismatic figure, the kind of character that seizes all available oxygen. Agu’s voice—so distinct, and so immediately itself—nonetheless bends to the will of the Commandant, reactive to threat and seduction of his erratic attention:

Commandant is kneeling next to me and smiling so I am seeing how his teeths is in his mouth anyhow, just yellow with gap here and there. His gum is black and his eye is so red. [. . .] He is stretching his glove to my face, grabbing it hard but also soft like he is caring for me, and then he is looking at all of the blood, and dirt, and mosquito bite, and mud I am having on me from dragging in the road.

From the start, the relationship between Agu and the Commandant is marked by this confusion between “hard but also soft, like he is caring for me,” by the terrifying and insidious nature of the Commandant’s attention. Beasts of No Nation is a story about abuse, both sexual and psychological.

It is also about the way the Commandant pulls Agu into an increasingly narrow, increasingly frightening definition of masculinity. He does this in part by erasing the past. Agu lives increasingly in the present, his memories of his family and in particular his father, his sense of another world and way of being, rapidly fading. This erasure, the novel seems to imply, is part of what allows Agu to perform atrocious acts of violence and murder.

Iweala does not shy away from depicting the sickening thrill the act of killing gives to Agu: “I am raising my knife high above my head. I am liking the sound of knife chopping KPWUDA, KPWDUA on her head and how the blood is just splashing on my hand and my face and my feets. I am chopping and chopping and chopping until I am looking up and it is dark.” In visceral and unrelenting prose, the novel troubles the easy distinctions between victim and perpetrator.

When I returned to Beasts of No Nation after a period of some years, I felt the jolt of recognition you feel upon encountering an old friend.

Beasts of No Nation also complicates our impulse to identify with the central character. We are with Agu from that first, startling sentence. We identify with innocence under duress, a way of reading that feels morally safe and secure. But over the course of his novel, Iweala shows us that we are equally capable of identifying with the monstrous—both in Agu, and his descent into violence and mania, but also, at least a little bit, in the character of the Commandant, who exerts his charisma both on Agu and on the reader.

We are meant, or at least I think we are, to feel shocked and distressed at Agu’s capacity for violence, a reaction that is deepened and complicated by the fact that we have identified so closely with a character who enacts violence without remorse. Our discomfort is in reaction to Agu’s transformation, but it is also in reaction to ourselves. The question of Agu’s humanity is never in question. Instead, the novel forces us to expand our understanding of what humanity encompasses, to question the limitations and the consequences of empathy.

When I returned to Beasts of No Nation after a period of some years, I felt the jolt of recognition you feel upon encountering an old friend. It was a strange and even unlikely response, given the nature of the character and the story. It is, perhaps, testament to the unrelenting intimacy of the voice and the novel. “It is starting like this.” From those words, we follow Agu, into the depths of a hellish and unrelenting war, through his multiple transformations, as he passes from boyhood to adulthood, shedding the last remaining memories of the past.

__________________________

Excerpted from the introduction to Beasts of No Nation by Uzodinma Iweala, out now from John Murray Classics. Copyright 2025 by Katie Kitamura.