Fortunes by Lucianna Chixaro Ramos

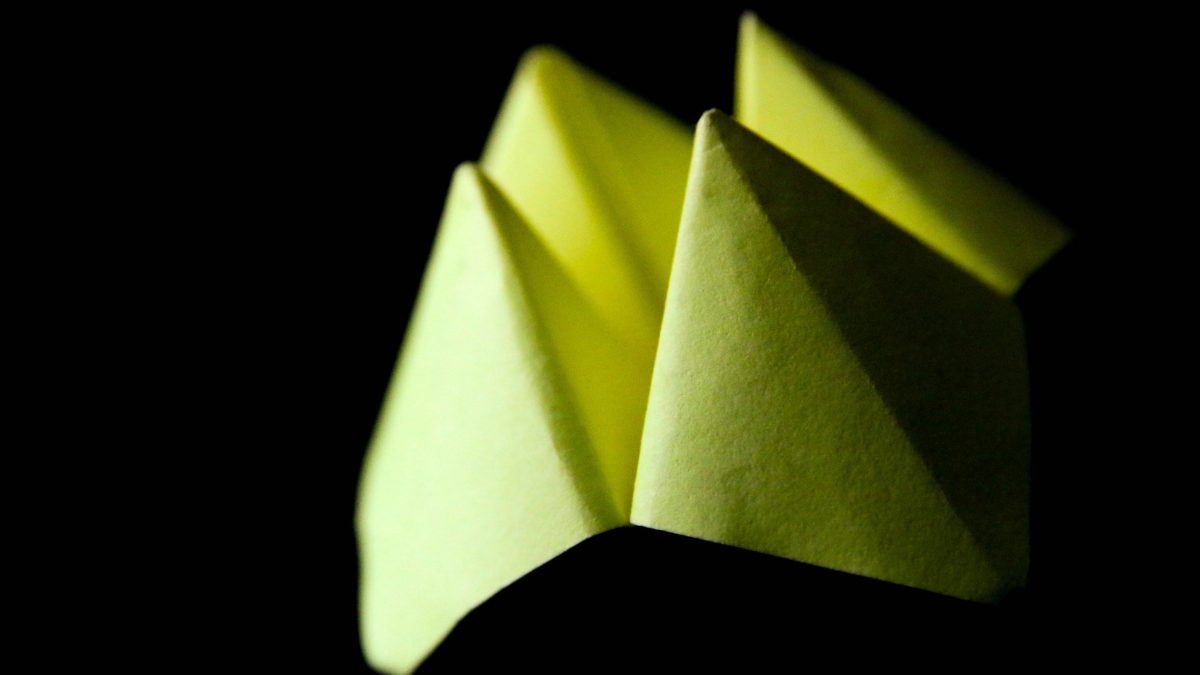

The summer we move into the crumbling mother-in-law suite, my daughter becomes fascinated with origami. It starts with a boat, then she graduates to other critters, and soon dozens and dozens of fortune tellers are strewn about the suite we rent for the summer. She writes esoteric phrases in place of the fortunes I remember from my childhood which focused on the possible attractiveness—or not—of a future husband or the size and quality of one’s house, hut, or mansion. One of her fortune panels reads plainly, “Let it go,” in curly, girlish script. This might be a Frozen reference but it’s also uncannily sage advice.

A year before our summer of fortune tellers, Amy tells me she will be on the school news with her guidance counselor. On the news, she will teach the other students how to make a paper fortune that contains different strategies to help them feel better when they are anxious or upset. But this time, her fortune-making is not as structured. This summer, her fortune-telling starts as a simple game to pass the time. We fold and fold as the clock ticks us deeper into summer, deeper into our unknown.

We rent the mother-in-law suite after secretly selling our blue house, and predictably, it is often stuffy due to the sweltering Florida heat. The place is just about to turn one-hundred and you can smell the years of cigarette tar encrusted onto the walls. So much tar in so much heat that eventually it drips down the walls, like blood from an old wound. A shared chlorinated pool sits between the French doors of the suite and the main house. The big rental house is rarely occupied, and when it is, the occupants don’t hang out by the pool much. At least one of the rotating cast of families seems unpleasantly surprised that there are people living in the backyard, though we try our best to be inconspicuous. One family piles black trash bags by the pool in a futile attempt to eradicate the bedbugs their daughter brought from her college dorm room. Between our two families, just that patch of stagnant water. A floatie continues its slow spin, an aimless raft waiting for someone to climb aboard.

To kill time, Amy and I head to the nearest air-conditioned book store. There, we come across a book with origami tutorials. The origami book is what ignites her renewed desire to create a near infinite array of folded creatures and fortune tellers. Like any story, a fortune begins as a blank page. Once crafted, written, and read, it becomes infused with meaning.

Back in the suite where tar and sweat still permeate the room, we hear the drone of my husband on the telephone working at the six-foot folding table in the lofted bedroom. He sits crooked, using the spring-mattressed bed as his chair, a posture that will later cause him pain. I cut up pieces of construction paper into squares so we can begin folding the origami. We make beavers and otters and roses. The instructions for the folds prove to be daunting. One otter looks more froggish than otter-like, one rose has a squashed side. Amy becomes frustrated at the imperfections, her fingers creasing the paper with a tense determination. Time and time again she goes back to the flower-like fortune tellers until she can nearly make one with her eyes closed. I ask her to teach me how to make one and she does so with surprising patience. “First like this. Then fold here,” she grabs my work-in-progress and flips it right-side-up as I fumble through memories of my own childhood creases. By the evening, a dozen of them are lined up on her digital piano’s matte black top. Finally there are so many we run out of room on the piano, so she makes an origami cup in which to put all of her origami fortunes. Folds within folds.

By mid-July, time in the mother-in-law suite slows to a stop. It has been a few weeks since I shoved the last of our belongings—high-heeled work shoes, clothes that didn’t fit in our suitcases, and unwanted dolls—into the trash bins outside the blue house. We’d been running out of time—the new owners would need the keys and we were due at the brokerage office. We’d been running—an ultra-marathon of police reports, hearings, visa paperwork, getting the family dog certified to travel, booking rental houses, and finally downsizing and selling the last of our things. When selling was too slow, we started giving. Then time ran out and everything became trash. There was a mandatory sequence of steps that followed a familiar logic: getting things done. But in the mother-in-law suite, all that is certain is the precariousness of forward motion: that a decision has been made and a swift cut followed. We are living in the interim—a lull between synapse firing, resulting thought, and action. The suite itself is a type of liminal space where all that exists is a summer, hot and tedious and barren. A summer like an enormous, pendulous mass. Like something about to burst. A cut before the blood comes.

I cut up pieces of construction paper into squares so we can begin folding the origami.

We make do with whatever entertainment we can find in between my hushed phone calls to airlines, my spreadsheet budgeting, all of which color the days before our final leap from one continent to the next. Between bouts of origami-making and sitting poolside by hordes of mosquitoes that skitter across the surface of the water, we take walks around a block of suburbia in a neighborhood so affluent we only ever see professional dog-walkers. Even the origami starts to grow tiresome, but Amy keeps folding, perfecting the petals of the roses and folding two papers at once so that each flower shows two colors. When the tedium hits a fever pitch, I grab one of her blank fortunes and sit down at the round kitchen table that doubles as a desk.

“I bet we can turn this into a story machine,” I say conspiratorially. “We can turn this one fortune into one hundred stories!”

She stifles a laugh and looks at me skeptically. That okay-mom-sure-you-can look.

Unfurled, a fortune is just a piece of paper with compartments for words and numbers. It is an innocuous object—a type of mirror onto which we project ourselves, with all of our expectations and aspirations, fears and apprehensions. Our visions of our future selves appear there, unscathed, heroic even. All of our complex problems are distilled into manageable archetypes. We twist and reframe the narrative shown by the fortunes, whether they are tarot cards, tea leaves, or folded paper, to mirror our hopes and neuroses, wishes and doubts.

On the outermost petals of the paper, I write the beginnings of sentences: “the dog,” “many pigs,” “two sad people,” and lastly, “one sad pony.” Inside these petals, the panel is split in two, totaling eight options for the next segment of sentence. Onto these I wrote verbs like “skateboarded,” “snored loudly,” “cooked,” or “skipped happily.” Then we open up the flower-shaped fortune and write along the triangular, splayed open petals, eight more phrases, each containing an adverb, so that we can situate our characters. Behind, inside, on top of. Underwater. In the center of the flower, I write eight more numbered phrases, this time focusing on a sense of place, whether abstract or palpable. A scary ice cream shop, a pink sky, a cold house.

I explain to her that from these petals we can make up silly sentences. “All you have to do is pick four numbers,” I explain.

“Four,” she says.

“Ok, ‘The sad pony…’”

“Four!”

“’The sad pony plopped…”

“Six!”

“’The sad pony plopped inside of …”

“Seven!”

“’The sad pony plopped inside of the dinosaur’s mouth!”

We twist and reframe the narrative shown by the fortunes.

Amy giggles. We tell each other lots of stories this way. We dub these fortune tellers story machines. Then we make another machine with as many variables as the first one. She asks me how many stories we can tell altogether. I pull up the calculator on my phone and dig into my foggy middle school memory of factorials. Using the current story machines we could make millions of stories.

I write it on the notebook paper’s header. A million stories.

As a joke I add, “By Mom.”

But the stories were there all along, ours for the taking.

Years before we sold the blue house, my husband and I found ourselves sitting across from our friends at a new year’s eve party where a hush had fallen over us. They brought each of us into their game room, away from the noise of the party, their faces almost comically intense. Carlos shuffled the cards. Heather peered curiously from under her waterfall of strawberry-blonde hair. Our host shuffled a deck of tarot cards for what, in my tipsy state, seemed like five whole minutes. Then he asked us to cut the deck. I cut once, then my husband. He laid out three cards with his long finger-nailed hands and sighed. I’m not sure if the sigh was an expression of his own anxiety—(should I tell them what they want to hear? the sigh seemed to say)—or what he saw in the cards splayed before him. He’d pulled the Nine of Wands, with an image of a worried male figure holding on to a staff, eight more staves visible in the background. He explained simply that, the problems we’d faced before, we’d have to face again—but we’d be better equipped this time.

We left and rejoined the rest of our friends, brushing off the cards as just another party game, the momentary quiet vanishing behind us. But I knew the problem represented by all those staves. It never seemed to go away no matter how much I prayed for it to be neatly stored away and forgotten, like a small, inconspicuous deck of cards. A sort of anxiety settled over everything like fine dust. Sundays were the worst. Each Sunday in the blue house, Amy awoke early. I made her breakfast and packed a bag with everything she would need for the day. We waited, both of us tense—I stood at the kitchen sink, nervously scrubbing a dish. She sat across from me, eating a piece of toast or drinking a glass of orange juice. Every few minutes, I glanced out of the bay window that framed our living room. Her father would finally arrive in a white sedan or a gray SUV, or some rental—whichever car hadn’t yet met its violent end—and I would strap on her court-mandated GPS watch and perform a silent, inward prayer. When she left, the prayer turned into paralysis. I often sat at the kitchen counter, wild-eyed, for the twelve hours he had her.

Those were our staves. But the symbolism of the Nine of Wands doesn’t just reveal strife. It’s also about grit and willpower. The ability to keep going even when the load weighs heavy on your shoulders, even when there is a feeling of running in place, of trying hard and getting nowhere. The futility of filling out another form, retelling the same, years-old story again, of spending another paycheck on yet another legal retainer. Many years passed in courtrooms, pleading with a rotating cast of judges to grant her protection, as they had granted me, from the man who harmed her. For many years, these requests for safety were made in vain despite investigations, an arrest, a conviction.

The card my friend pressed down onto the small table between us showed me our hurt, the worst of it happening again—but also our persistence, how close we were to peace, that yet unimagined promised land.

Carlos and Heather’s reading wasn’t my first encounter with the tarot. As much as I tried to stay away from any sort of mysticism, I kept running into it over and over, like a bird flying into unseen glass. A decade earlier, I had loitered around a tarot shop with two girls from school. We were in Cassadaga, a town in the heart of Florida known to some as the psychic capital of the world. Vicky and I were waiting for our turn to have our cards read. Blake, the girl who drove us and whose idea it was to skip school and drive to Cassadaga, was sitting outside drinking a tallboy and muttering under her breath about how ridiculous this whole town was. We tried to shush her disbelief before she disturbed the townspeople and we were forever cursed. An oddly cool wind seemed to blow.

I often sat at the kitchen counter, wild-eyed, for the twelve hours he had her.

We’d been trying to figure out something to do on a cloudy day in a strange Florida winter, a January in which I had seen tiny, incongruous snowflakes fall onto my grandparent’s back porch and into their pool. The rarity of the snow made us reckless. Our misadventures took on a new poignancy—as if we were trying to outshine the bad omen of the southern snow by smearing our bad decisions all over it.

The woman in Cassadaga read my cards first. My memory of her card spread is a blur, but I remember that she predicted my relationship with Vicky would change dramatically in the years to come. That we would no longer see each other like sisters. We’d grow apart, eclipse each other. For some reason this shocked me into silence—I never told her what the woman said. Or maybe I willed that narrative into existence, reflecting back on the meaning of the cards, and realizing our friendship was deeply flawed and unbalanced. Maybe the cards confirmed a feeling that already existed in me that our friendship was something outgrown and better left alone, like a stubborn weed.

After high school, when her father passed away, we lived together for a short, turbulent period. Then, I focused on college and she moved up north. Our paths diverged. I heard from her in passing, but never saw her again.

Mysticism marked the edges of my childhood from the start. Early on, my mother traded Sunday mass for afternoons reading Allan Kardec in her best friend’s incense-laced apartment, while toddler-me pretended to take showers beneath an enormous hanging pothos. She had converted to Spiritism. She believed in past lives and soul mates and serendipity and fate. And she liked to have her cards read.

Once, on a foggy Rio afternoon, I was a four-year-old in a fortune teller’s tent, smelling the salt air and trash heaps—that rancidness that sometimes still reminds me of Rio—through the rips in the plastic. The woman drew cards in a cross pattern. Then, she gave my mother the grave warning that would haunt her for the rest of her life: that she would never marry happily. My mother took this as her life’s greatest challenge—one she pursued with incredible zeal. By the time her fortieth birthday rolled around, she had married and divorced four times. The first marriage was to my father, a man who sent her love letters from the bad side of town. The second was to a sweet Argentinian man with a pill problem and a safe full of secrets. The third was to my brother’s father whose blow with a two-by-four left a permanent, lightning-shaped scar through her left eyebrow. Lastly and most briefly, she married a man who claimed to be a dentist and donned tattoos written in Hebrew he never wanted to discuss. Within a month of their split he was married again. In trying to prove one woman’s prediction wrong, she only proved it right, time and time again. The pivotal moment of her life could be traced back to a single narrative she fought relentlessly against—a destiny predetermined in a spread of illustrated cards.

My mother traded Sunday mass for afternoons reading Allan Kardec in her best friend’s incense-laced apartment.

Despite my slow orbit around the world of tarot, I never had my own deck until after my thirtieth birthday. Perhaps because of the memory of my mother’s ominous reading, I was superstitious, thinking that someone would imbue the cards with bad luck, or even that asking a question myself was too selfish of a reason to have a deck of my own. I considered tarot a gift that had to be offered. Then, a literary magazine I read released a twentieth anniversary commemorative deck. Each card included an artwork or poem written by a contributor specifically for that symbol. It seemed like the perfect opportunity to begin a collection.

Still, I kept the cards close to my chest. I drew cards in the shapes of crosses in the walk-in closet while I pretended to get dressed for work or in the upstairs office, when no one else was home.

When we are finally ready to say goodbye to the cramped mother-in-law suite and move across the ocean, my daughter packs her fortunes, the story machines we’d made during the long summer, and the blank ones, too. I tell her we won’t be able to take all of them, so she places the ones she wants flattened into their green origami cup and packs them up in her rainbow backpack so that they almost take up no room. That she wants to bring the fortunes with her is a reminder that she, too, loves stories and all of their infinite possibilities. If, after everything, she can still hold onto the vastness of her own narrative, then she—and by extension we—would be OK. Our stories are still ours to write.

It was night, one of the last we spent in the blue house. My husband and I sat in the office room with its twinned desks amid the half-taped boxes with our years’ worth of stuff spilling out. Only a single lamp was lit. It smelled pitiful like cardboard and dust—the familiar scent of leaving. The giant oak in our backyard was being rocked by another summer storm, a summer that still housed within it the potential of forward motion.

“Ask it,” my husband said with an uncharacteristic tinge of nervousness.

I shifted uncomfortably on the comically small turquoise futon we had bought on our limited budget for houseguests.

“Then we can’t take it back,” I said.

“Just ask.”

I whispered a tentative, “Okay,” drawing in a slow breath. Then I cut the deck.

I drew a card. Then another. And then a third. I had always been skeptical of any sort of divination, but superstitious enough to get nervous, believing once we see a story in the cards, it is hard to turn away from the throughline. We will it into existence, good or bad. Suggestible as humanity is, we are liable to place everything on the line, the entirety of our faith, on a single, however implausible, story. I tried to concentrate on the issue at hand, the questions we couldn’t say out loud to each other but felt just fine asking an inanimate stack of cards: Will we be safe during our escape? Will this crazy thing we’re doing work?

The deck felt heavy in my hands. I cut and shuffled it over and over delaying the inevitable answer. Then I grit my teeth and cut it one last time, exhaled a final breath that hung in the air like a question. If we leave will we be safe? Will he reach us, somehow, from across the Atlantic? I let the thought fill my mind while I placed the cards down on the desk’s wood-like veneer. Five cards in a neat row. The past and the present, then the challenge. Advice. Lastly, there was the card of outcome. As I placed the cards, our eyes latched onto them as if they had a gravitational pull.

I had always been skeptical of any sort of divination, but superstitious enough to get nervous.

As soon as I pulled the outcome card, I felt the familiar sting of tears. The Six of Swords card of this particular deck has no image. It lay on the wood-veneered desk, a temporarily impenetrable object. In the place of an image was a sliver of prose by the novelist Rick Moody. In it, he described a surreal, shifting scene with a dreamlike narrative. It is hard to grasp the facts of the story. The reader knows there is a mother and a daughter. There is an investigation. There is a departure. We’re not sure who leaves or who stays, but there is the sense that, in the end, there was a messy break toward a new beginning. “Liza cleaved desperately to her mother, and they clambered aboard the skiff, backs to us, onto a river of forgetting,” wrote Rick Moody in his interpretation of the Six of Swords. I couldn’t explain all this to my husband, who sat anxious and silent, while I processed the card’s meaning. The weight of the six of swords appearing in the position of outcome was equivalent to the weight of the story of safety and freedom we were telling ourselves. It is always the story that happens first—that allows us to believe that anything is possible. Before any pivotal event there is a precursor, a primordial narrative that hovers above us, shimmering. We only have to reach for it, to hold it close enough to see ourselves in this mirror of possibility.

In the traditional Rider-Waite deck, the six of swords depicts a hooded woman and a child huddled onto a raft being directed by a man, who the viewer assumes is helping them to escape. There are six swords in the water, representing hardship, but depending on the deck, the swords are split between the space in front of the boat and behind it, suggesting there is more suffering to be had, but some of it has already passed. One can separate oneself from the unimaginable danger that is never depicted on this card, the secret part of the story only the querent knows. To see our story reflected back to us in the symbolism of this card gave me the sudden feeling of freefall. It gave credence to the story we had already begun to rewrite. What we wanted—what we already knew—was that our pain didn’t have to be the ending.

Later, when we make it across the ocean—all three of us and even the colossal white dog—I see the swords clearly, those we’ve escaped and those still ahead. No longer are we passive observers to our own calamities. No longer waiting. We are afloat now, basking in the warm certainty of the sun. From my place on the raft, I reach into the water and grasp the hilt of a heavy sword.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven’t read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

YOUR INBOX IS LIT

Enjoy strange, diverting work from The Commuter on Mondays, absorbing fiction from Recommended Reading on Wednesdays, and a roundup of our best work of the week on Fridays. Personalize your subscription preferences here.