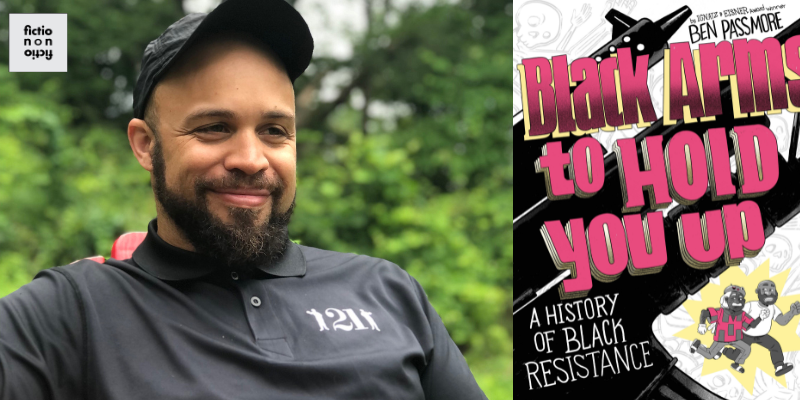

Graphic novelist Ben Passmore joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss his new graphic novel Black Arms To Hold You Up: A History of Black Resistance. Passmore explains the mix of personal reflection and historical storytelling in the book which follows the main character, a version of himself, time-traveling through a century of the Black radical tradition. Passmore talks about imagining a fictional self visiting Black historical figures and spotlights Assata Shakur, a well known member of the Black Liberation Army, who passed away last month. Passmore reflects on Shakur’s life and considers how her story highlights the broader struggles and resilience of Black activists whose work is marginalized in mainstream histories. He emphasizes that the book focuses on less prominent figures within the Black radical tradition, providing a corrective to previous whitewashed narratives. He talks about activists and thinkers interested in goals ranging from liberation to reform, as well as community-based forms of resistance and education. Passmore reads from Black Arms To Hold You Up.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/ This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, Bri Wilson, Emma Baxley, Hope Wampler, and Elly Meman.

Black Arms to Hold You Up • Sports is Hell • Your Black Friend and Other Strangers

Others:

We Will Return In The Whirlwind Black Radical Organizations 1960-1975 by Muhammad Ahmad — Charles H. Kerr Publishing • Going to the Territory • Assata • Assata Shakur, an icon of Black liberation who was exiled to Cuba, dies aged 78

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH BEN PASSMORE

Whitney Terrell: We studied with a professor named James Alan McPherson at the University of Iowa, and he would talk a lot about a division in the Black community about how to think about resistance, which I consider to be ways of thinking about America. People like Bayard Rustin or Ralph Ellison or James Alan McPherson who argued against the ethics of Marcus Garvey, Stokely Carmichael, and John Africa. For instance, Ellison’s essays Going to the Territory advocate for something that he calls unity and diversity in America, which involves cooperation, borrowing, conversation, sometimes antagonistic cooperation, among racial groups. How do you view that part of that conversation? What’s your attitude on thinkers like that compared to the people that you’re emphasizing in the book.

Ben Passmore: In some ways, your question is an example of grouping together all Black political tendencies because we are all Black when, clearly, we have very different goals. We have materially the same problem. We are a colonized population within a white fascist country. But to be totally honest, I wouldn’t even say that everyone is as equally credible as Stokely—whose name isn’t Stokely, it’s Kwame Ture. He is, in my mind, more credible than Bayard Rustin. Mr. Rustin collaborated with the CIA to rig an election in the Caribbean. Anyone with a position against violence loses their credibility when they work with the CIA. In this case, they’re not necessarily having a conversation about the same thing. I wouldn’t say that the difference between historically, Carmichael and Ralph Ellison, is necessarily a disagreement on violence. I think a disagreement on violence in America feels a bit besides the point. The country is incredibly violent. The government has been very good at figuring out ways to cover over the violence.

And I think the right wing and maybe liberals, people that I view as a bit more centrist, particularly as it pertains to Black liberation, they have different approaches. We’re seeing the liberal approach in the conversation around something like antifa. The common joke right now about antifa is that, “Oh, you must mean World War Two soldiers, because that’s antifa.” Never mind white World War Two soldiers’ relationship to segregation within the army itself, and ensuring that Black veterans couldn’t be entitled to the same VA resources, couldn’t move into the same neighborhoods that white veterans moved into. To me, that’s not anti-fascist. And never mind that there is an actual anti-fascist movement, not only in Europe, but one that’s existed in the United States. There was this huge peak between 2000 and about 2018 where there was a decentralized anti-Fascist movement that’s responsible for Richard Spencer going home, for Matthew Heimbach being humiliated. That didn’t happen because, you know, we made fun of them on YouTube. Anti-fascists punched them in the face until they decided that it wasn’t worth it to be outside.

The proposed conversation that people often want to have about this is whether or not we should be violent. To me, that feels like a meaningless question in most cases, because the violence is here. I think the question is, what do we need to do to survive? That’s the question I asked myself as a Black person who feels that I am part of a tradition of liberation and not reform. Those are very, very different. Bayard Rustin, outside of my critiques of him, is a reformist. Kwame Ture was not. There are real questions around violence that are really important, and I try to cover them in the book, the emotional reality of no matter how violent you are individually, it will not provide freedom. I don’t write about a single moment of a war of independence in the book that’s not part of this tradition. It’s mostly defense and retribution. Most of the Black violence in the United States has been about survival, and in my view, it’s the only reason that I am here. I’m a product of Black people’s willingness and ability to fight for their own defense. This book is not really for white people, but I think if white people are looking for some perspective on how to think about violence, the first place to start is to understand the difference in people’s analysis and goals. Some people want, in the case of the Republic of New Africa, an independent Black nation cut out of the United States. Ralph Ellison doesn’t want that. And that means that they’re pursuing their goals very differently. Because, of course, the Republic of New Africa isn’t going to try to get political party members in Congress. This is very much besides the point.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: Thank you for that complication and context. This is sort of what I meant when I said that I appreciate the way that the dialog between the Father and Son makes it so that I get that it’s not a book for me, even as it’s a book for me. We’re recording this on Saturday, October 18, which is the day of the No Kings protest. Some of the rhetoric around this in our decimated media has been about violence: “Are you going to get gassed? Is the National Guard going to go after these protesters who are ‘antifa domestic terrorists?’ How do we prepare ourselves?” We’re at this interesting juncture in the way that mainstream discourse is considering violence, and some of it lies in the questions that you’re saying, for you, don’t have particular meaning like “Should we be violent?” We had a guest on the podcast a couple episodes ago, Yiming Ma, who was talking about survival as a mode of resistance. So I think about that. We also had Farah Jasmine Griffin on the show talking about censorship of the Black canon and and I’m really interested in the ways that, as education is kind of devastated, we can turn to, specifically, Black communities and Black traditions, and also Jewish communities and Jewish traditions, and I’m sure many others, where we’re educating ourselves outside of state controlled mechanisms of education. There’s community education if the state is going to censor your education.

One of the things that your book does that’s interesting is there’s this reference to this historical archive of documents. These documents are quotes. There are facsimiles or versions of documents in the book. The book is about violence, and it’s also, like all books, about reading. It’s about the way the story of violence is told and the way that the “Ben Passmore of the book” is reading and understanding those texts he hasn’t seen before. It’s a book that explores the buried history of Black Americans using violence. It also ends with Ben’s father throwing books at the police. I wonder if you can talk a little bit about how you put reading into the book, and how you think about, the questions that we’re talking about in relation to violence, in relation to reading, and how you thought about building that into the book?

Ben Passmore: Just another point of clarity, it’s actually me dressed as my father. I appreciate the question. It’s not a book about violence. I had a suggestion from a friend I respect early on in the scripting of the book. He suggested that I carve out a section to make the case for what many people in the book would call armed self defense. My general view is that debates around violence, not to go back to my early response, but in many ways just hold us back, particularly the conversation of “Is violence moral?” Given the state of the country, that the fascist third position is in the White House, that feels equivalent to asking “Is the rain inconsiderate?” Let’s just do what we can to not get wet. To bring it back to your question, I felt like an essential part of that was engaging in a kind of education that doesn’t rely on institutions, especially in this time when they’re deeply unreliable. For the Black radical tradition, they’ve been unreliable. Many people, including members of the RNA, were part of the fight for Black Studies, you know. There are a lot of very respectable academics that have done a lot of really amazing work in Black Studies and Africana Studies. That’s done a lot of good for a lot of people. But we’re seeing right now that this is not permanent.

And something that is fortunate—I can say, for an area that I know quite a bit more about—what’s fortunate about the Black radical population is that we have relied on sharing information for study. There’s a long history of what my dad is in the book. We joke about hoteps, but hoteps are generally containers of what they perceive as forbidden and true information, you know? Unfortunately, if you go to an Israelite bookstore here in Philly, like Black and Nobel, very inaccurate histories of Africa are right next to Mohammed Ahmad’s book about the Revolutionary Action Movement. Muhammad Ahmad was a participant in the civil rights movement in the 50s, and then moved on to a proto-Panther underground organization. Amazing book that many people have not read but it’s right next to a book that is, in my view, nonsense. Some of my approach to this book was trying to recreate the experience of learning from your elders, learning from your community, learning from books in a Black bookstore where you’re like, “I’m not 100 percent sure if this is true but knowing that, I can’t be sure, what does that mean in terms of how I’m going to respond to my conditions? What actions am I going to choose to take?”

At the end, a couple of people have asked, or assume that what I’m saying with the Ben character choosing not to use the gun and to throw books, that this is ultimately a pacifist ending, and it’s not. Once again, the debate in the book is not over whether or not people should be violent. Like I said, it’s irrelevant. What my father ultimately says is, “be here for the right reasons, fight for the right reasons.” It’s not about acting out self hatred. It’s not about self destruction. It’s about freedom. It’s about living well. My main issue with the idea that survival itself is resistance—and I don’t disagree—but I think often the conversation ends there. For me, I want to live well, and part of my anger living in this country is that that’s made almost impossible. I can’t live on my own terms. I can’t live well. For many guerillas, certainly the people I wrote about, they’re willing to fight for that right. They’re willing to risk maybe not living at all and maybe going to prison because they want to live on their own terms. For me, it’s been really essential to read a lot of great information, and to come at the world filled with knowledge and all these ideas of, in my view, much smarter and braver people than myself.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy. Photograph of Ben Passmore by Tina Furr.