Mapmaking, if you do it properly, is a time-consuming and money-consuming business. You have to do field surveys and travel to multiple locations, some of which can’t be accessed in a vehicle. You have to measure distances, angles and elevations using heavy, cumbersome equipment like theodolites, leveling instruments and very long tape measures. And once you’ve gathered this data, it all has to be painstakingly compiled using either computers or triangulation and maths, depending what century it is.

Article continues after advertisement

This is a complicated enough process when just drawing a map of the basic shapes of an area, but the job gets even harder if your map needs to include labels. Even if you’ve got your own satellite photography kit knocking around, which—by the way—is even more expensive to maintain than tape measures, this will tell you nothing about the names of all the towns, streets, parks, schools and so on. Getting information like this requires yet more careful surveying.

And what of all the important features that your map needs to show that are invisible from the ground, like administrative boundaries, or roads that have been planned but not built yet? Obtaining such data requires liaising with various government departments, some of whom don’t respond to emails for weeks.

So, with all this in mind, it’s easy to see why the temptation is so strong to not do mapmaking properly. Instead of going through all that rigamarole, why not simply trace the information you need from a map that’s already been made? After all, how would anybody know? Two separate companies surveying the same real world should end up with exactly the same results.

Paper towns are like background extras in movies—if you notice they’re there, they’re not doing their job properly.

Plagiarism is a genuine problem for mapmakers, one that only gets worse the more detailed their map is. The closer it reflects the real world, the harder it is to prove that there has been any creative process at all. So, when cartographers have gone through all the extensive and expensive effort to gather the data for their maps, how do they protect themselves from other companies copying it for themselves and passing it off as their own, with slightly thicker lines, bolder colors and a chunkier font?

It turns out, mapmakers do have a trick up their sleeve to stop this from happening. It’s a centuries-old method that enables them not only to spot when their work has been stolen, but also, if necessary, to be able to prove it in a court of law.

The idea is…and it’s one of those ideas that’s so stupid it disappears off the stupid side of the stupidity graph and reappears on the clever side…you make your map wrong on purpose. All you have to do is put a deliberate mistake on your map that definitely isn’t in the real world. If that same mistake turns up on someone else’s map, you’ll know the only place they could have got it from is your map, and…busted!

Incidentally, this concept where creators add subtle little incorrect details to protect their copyright isn’t just limited to maps. You can (or, if they’re doing it right, you can’t) find made-up words in dictionaries, fictional entries in encyclopedias, fake phone numbers in phone books, non-existent businesses in business directories, meaningless strings in software code, extra screws in architectural plans, bad advice in medical textbooks and glaring factual errors in light-hearted books about maps.

Copyright traps on maps can take many different forms. Of course, they don’t work if they’re massive howlers like putting New York on the west coast of Africa, or turning Japan inside-out, or adding a dense network of protected cycle lanes across the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. The trick is to add a false detail that’s small and subtle enough to go completely unnoticed and cause no trouble to the map user, but easy enough to identify if it turns up on somebody else’s map. Getting this balance right is a real skill. It also sounds like a right hoot.

Sometimes it can be a harmless spelling mistake. “Book Mews” in central London is shown in the iconic London A-Z as the more plausible sounding “Brook Mews.” But it’s a tiny dark alleyway off a side street that only three people live on, so it doesn’t cause any nuisance. It’s rumored that the A-Z has at least one “mistake” like this on every single page.

Sometimes map traps can be subtle alterations in the physical make-up of the map, such as bending a mountain contour the wrong way, or making a very squiggly road slightly squigglier. A 2011 map of the Swiss Alps produced for Swisstopo by cartographer Paul Ehrlich has contorted contours that look like a marmot climbing up the side of a mountain. This was drawn just before his retirement, so it was probably done for the purposes of mischief rather than copyright protection. What were they gonna do, fire him?

Mapmakers, knowing that there are hidden traps in their rivals’ work, tend to stay away from copying each other.

But by far the most well-known, easiest to prove and most fun type of deliberate mistake is a feature such as a building, a street or even an entire town that simply doesn’t exist. Towns such as this that appear only on paper are known as ‘paper towns’. And they are everywhere.

The 1978 edition of the official state of Michigan map shows the fictional cities of “Goblu” and “Beatosu” in the thin strip of neighboring Ohio at the bottom of the page—the names being a not at all subtle dig at the University of Michigan’s rival Ohio State University. (“Go Blue” and “Beat OSU.” Get it?)

The town of “Argleton” in Lancashire existed only on Google Maps until 2010, when it was quietly deleted from their database, probably because word started to spread when somebody clicked the “satellite view” button and revealed it for the empty field that it was. (They might also have spotted that “Argleton” is a somewhat unsatisfying anagram of “Not real G.”)

And those are just a handful that we do know about. Paper towns are like background extras in movies—if you notice they’re there, they’re not doing their job properly. That means there are countless more out there, but, by their very nature, we don’t and can’t know about them all. Many of them are hidden in old maps whose cartographers are long dead, and so they may never be discovered.

Paper towns are also a bit like car alarms or nuclear warheads—while it’s nice to know they’ll do their job in the worst-case scenario, their main reason for existing is to act as a deterrent. Actual court cases where plagiaristic defendants stand in the dock sputtering and blustering over blatant copying are disappointingly rare. Mapmakers, knowing that there are hidden traps in their rivals’ work, tend to stay away from copying each other. All the different companies make their own maps from scratch, sending their surveyors to the same locations in an inefficient atmosphere of mutually assured litigiousness.

__________________________________

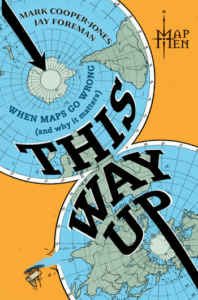

Adapted from This Way Up: When Maps Go Wrong (and Why It Matters) by Mark Cooper-Jones and Jay Foreman. Copyright © 2025 by Mark Cooper-Jones and Jay Foreman. Published by Hanover Square Press, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.