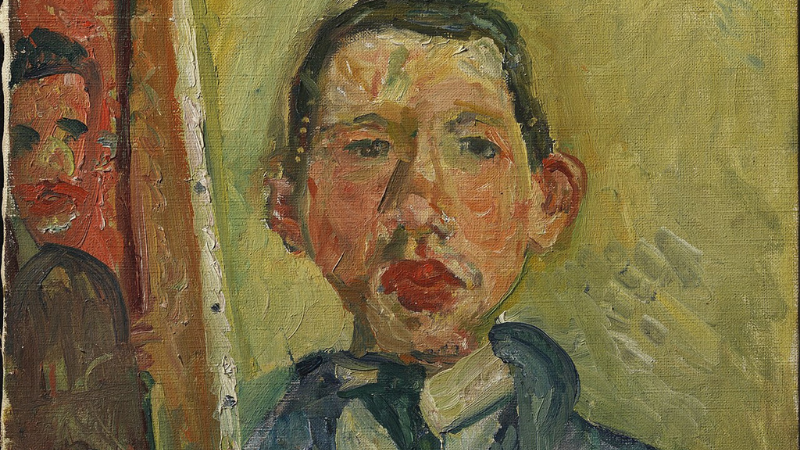

By the end of 1923 Chaim Soutine was known on both sides of the Atlantic as a formidable painter. He had an allowance from Zborowski of twenty-five francs a day and a personal chauffeur paid for by the dealer. Young painters would sit at La Rotonde ostentatiously reading The Brothers Karamazov and Crime and Punishment—Soutine’s favorite novels—hoping to catch his eye.

Article continues after advertisement

In 1924 the film director Jean Epstein asked Soutine to make a brief celebrity appearance in his bizarre film Les lion des Mogols. About an hour into the movie, a smiling and indisputably dashing Soutine dances gleefully alongside none other than Kiki de Montparnasse—“The Queen of Montparnasse”—one of the glitteriest and sexiest figures of les Anneés folles.

The Soutine who returned from Céret in late 1922 would hardly have recognized the dashing dancer in Epstein’s film. No one, least of all Soutine himself, could have foreseen such an enormous transformation. Zborowski certainly didn’t. He drove all the way down to the forested village in the Pyrenees where Soutine was ensconced and crammed his car’s trunk full of the canvases that he managed to salvage from Soutine’s immolations, and then grimly wound his way back up to Paris, thoroughly expecting to earn back exactly none of the money he had spent on Soutine in Céret. The painter was considered unsellable at the time.

Barnes would change all of that. He made his massive Soutine acquisition while still in the early stages of assembling what remains one of the most impressive collections of modern art in the world.

Pinchus Krémègne recalled standing in Zborowski’s house in the country shortly before Albert Barnes acquired the works. “There in the room, [Zborowski] brought seventy unframed Soutine paintings. He started casting the canvases onto the ground one after the other. He looked at them and said to me ‘What can I do with all this!’”

Barnes would change all of that. He made his massive Soutine acquisition while still in the early stages of assembling what remains one of the most impressive collections of modern art in the world. He was not unusual among wealthy art collectors for being eccentric, acerbic, and exacting, but he was markedly and impressively capable of recognizing and nurturing promising young painters, and of esteeming them as on par with the Old Masters.

Unlike his friends Leo and Gertrude Stein, Barnes hung his avant-garde purchases next to great works from the thirteenth century, as well as canvases by Chardin and Renoir. Barnes’s impact was calculated. He was rigorously philosophical, and he had his own theory of art and art history, which he codified in a long treatise titled The Art in Painting (1925). That theory informed the way he organized his paintings and how he taught art history at the school he established in his mansion in Merion, Pennsylvania.

Albert Coombs Barnes was born in 1872 to a poor family in a rough part of Philadelphia known today as Fishtown. His father was a butcher who lost his right arm and his livelihood during the Civil War at the Battle of Cold Harbor. He collected a disability pension of eight dollars a month and scraped by working odd jobs. Barnes’s mother was a passionate Methodist who took her son to camp meetings and revivals run by the African American Methodist community in Philadelphia, instilling in the young boy an early, formative affinity for the principles of what would later become the civil rights movement.

Albert attended the competitive public Central High School, where he met and formed a lasting friendship with William Glackens, who became a significant American painter and advised Barnes in his early collecting gambits. Barnes graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School in 1889, paying his way by tutoring, boxing, and playing semiprofessional baseball.

Those twenty paintings formed the beginnings of a historic collection, of which Barnes was, in his lifetime, notoriously possessive.

After graduating he worked as a resident physician at the Pennsylvania State Hospital for the Insane. His time there marked him. Decades later it allowed Barnes to roll his eyes at the accusations of lunacy leveled by critics at the avant-garde artists he came to champion.

Barnes never practiced medicine again. Instead, he spent his meager savings on a flight to Germany, where he studied chemistry for several years. He put the study to good use, and after a number of successful business ventures, founded his own company in 1908. That same year he patented the recipe for Argyrol.

You may have heard of Argyrol if you’ve ever visited the Barnes Foundation and read about the founder’s fortune. If not, you may be forgiven for not knowing that the substance is an antiseptic that has various medicinal virtues. It was a lucrative discovery. Lucky for Barnes, for Soutine, and for us.

By 1911, just two years before Soutine’s arrival in Paris, Barnes had accumulated enough capital to instruct his aesthetic coconspirator William Glackens to go to France with $20,000 and return with as many masterpieces as that money would buy. It bought twenty paintings. (Today’s equivalent, roughly $6.5 million, would be barely enough to buy one of the paintings that now grace the walls of the Barnes Foundation.)

Initially, they hung on the walls of Barnes’s factory and were used in the lectures he held about art history for his employees. Those twenty paintings formed the beginnings of a historic collection, of which Barnes was, in his lifetime, notoriously possessive. He set up his collection in Lower Merion, a suburb of Philadelphia, and kept his treasures under lock and key. Only Albert Einstein, John Dewey, and the actress Katharine Cornell were allowed to visit whenever they liked. Everyone else had to apply for permission, and many were rejected. (Among them was the great art historian and critic Meyer Schapiro, who was turned away repeatedly.)

The exact circumstances under which Barnes first saw Soutine’s paintings are obscured by the many, contradictory accounts left by those involved. Barnes himself recounted contradictory versions of the story. Paul Guillaume, Léopold Zborowski, and Jacques Lipschitz all claimed credit for introducing Barnes to Soutine’s work. (Of course the fact that they clamored for credit is a testament to the importance of Barnes’ acquisition.)

The “unsellable” Soutine made his agent a lump sum of 20,400 francs in that transaction.

In one account Barnes said that Zborowski showed him Soutine’s paintings in 1921. In another he said, “The first time I ever saw a Soutine was in 1922 in a small bistro in Montparnasse and I bought it. Paul Guillaume [who by then was serving as Barnes’s primary agent in Paris] was with me and he knew that Zborowski had a lot of Soutine’s paintings.” Zborowski remembered things slightly differently. He reported that Barnes saw Soutines for the first time while visiting his home on the hunt for paintings by Modigliani and Kisling. Guillaume, for his part, recalled that Barnes caught sight of Soutine’s The Pastry Chef while at his gallery and fell immediately in love.

Whatever the case may be, Barnes did buy that canvas from Guillaume in 1922 for 3,000 francs. In December of that year or January of the next, the American millionaire spent just over 37,600 francs total on Soutine canvases. He bought primarily from Zborowski, who had the most to offer.

The “unsellable” Soutine made his agent a lump sum of 20,400 francs in that transaction. Guillaume sold Barnes another fifteen paintings in addition to The Pastry Chef, and Barnes bought a final canvas from the dealer Georges Aubry. He returned to Lower Merion in 1923 freighted with fifty-four Soutines. He would acquire only another five in his lifetime, but that first purchase changed Soutine’s life.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Chaim Soutine: Genius, Obsession, and a Dramatic Life in Art by Celeste Marcus, copyright ©2025 by Celeste Marcus. Used with permission of PublicAffairs, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.