Satire is often the most elegant way to interrogate society’s excesses, its shortcomings, its inequities, and its self-aggrandizement. Great satire hits a nerve. The use of humor may seem to soften the blow, but it lands a blow nonetheless on the subject of its scrutiny—individuals, governments, cultures, and systems. Best to punch up, not down, of course.

Article continues after advertisement

What about punching within? For me, in writing my forthcoming novel Intemperance, it began as a tool for self-preservation. If my protagonist’s motives were laughable and actions absurd, I needn’t write too close to the bone. With a protagonist whose life circumstances were undeniably drawn from my own, I was flirting with the “accusation” of autofictionalizing. Detouring into satire would give that notion some pause and would give my writing some wings, liberating me from self-consciousness and untethering me from reality. I could simply get out of my own way.

As a writer of color, though, I had to push past my misgivings about the expectations readers and critics may hold, especially from narratives by women writers of color.

In looking around for examples of authors who satirized versions or aspects themselves in fiction (examples abound, of course, in memoir, from David Sedaris to Nora Ephron to Mindy Kaling), some who came immediately to mind were Gary Shteyngart, Andrew Sean Greer, Otessa Moshfegh, and, yes, Nora Ephron. These writers have used fiction as a vehicle for “self-satire” to create a certain level of distance from oneself that can blunt the sharpness of self-criticism, and also create a sense of “ironic” distance that facilitates a stylization of fact and an ability to caricature, which can open avenues especially for wry or dark humor.

Long before these contemporary examples, Jane Austen offered, in Northanger Abbey, a heroine who expects her life and love to follow the melodramatic tropes of Gothic novels of the kind Austen is said to have herself enjoyed. Her protagonist, known to have been derived from herself in a few other ways, blunders along and is charming but delusional, unlike Austen’s fiercely independent and witty Elizabeth Bennet.

Nora Ephorn’s 1983 novel Heartburn draws heavily from her own life and satirizes the breakdown of her marriage. Ephron gives Rachel, the character modeled after herself, a handful of upper middle-class neuroses and places her in group therapy. She also turns her dry wit on the act of writing a novel, providing a paradigmatic example of “self-consciousness” as the motive force for humor. In My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Ottessa Moshfegh gives her protagonist elements of her own experiences with alcoholism and conjures a story that makes us laugh and grieve for the young female protagonist, then cringe and lie awake contemplating our own humanity.

As a writer of color, though, I had to push past my misgivings about the expectations readers and critics may hold, especially from narratives by women writers of color. I come from a rich tradition of satire by writers from my country of origin, India. In a recent shining example of self-reflexive satire, Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand (translated in 2022 from Hindi by Daisy Rockwell), gives us an 80-year-old Indian woman protagonist whose decision to travel to Pakistan disrupts the family’s expectations of women her age. What we get is a complex novel of women’s self-determination and sexuality within a story of trauma and displacement during the partition of India and Pakistan after independence from British colonization. I was inspired by this book’s characterization of Ma, the protagonist.

From what one can see in contemporary American publishing, satire from writers closer to my identity are few and far between.

In Intemperance, I seized upon the opportunity to write this new sort of coming-of-age narrative, one in which a woman in middle age (or even later in life, as in Shree’s book) finds herself shedding more and more convention and sometimes staggering, sometimes quietly swimming toward an awakening. The fact that this is to the dismay of her family allows for satirizing the family unit itself.

From what one can see in contemporary American publishing, satire from writers closer to my identity are few and far between. Yes, we have masterful satirical narratives from Zadie Smith, Celeste Ng, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Danzy Sena, Kiley Reid, and R. F. Kuang, amongst others. Their biting wit turned upon whiteness and the colonizer has served as much inspiration. But I also crave messy, older female protagonists of color who are losing the plot, so to speak.

A younger such protagonist exists in the darkly humorous 2016 novel Problems, by Indian American author Jade Sharma. Her protagonist, Maya, is a young woman with several life challenges including a heroin addiction, who has an introspective, self-critical attitude. In an interview, Sharma said, “I wanted to make a character that was as smart and self-aware as I was.”

Self-awareness, or the lack of it, both serve well in satire. In my first novel, The Laughter, the middle-aged white male protagonist is an English professor who doesn’t understand why the university must give in to demands for a more diverse curriculum and faculty rather than simply teach about truth and beauty from the literary canon. He lends himself oh-so-guilelessly into my hands for ridicule.

But satirizing a character quite a bit like me proved harder. I needed to find that sweet spot between the character’s rising self-awareness (for the sake of insights and wisdom so that my protagonist has a rich interiority) and declining control on the things she sets into motion. The latter was best done by manipulating the plot. She had to make some poor choices, some unenviable errors of judgment.

Drawing from one’s own circumstances can also help create a highly distinctive and powerful sense of place and a richness of critique of a societal setting that can be difficult or impossible to otherwise achieve. No better example comes to mind than John Kennedy O’Toole doing this to great effect with New Orleans in A Confederacy of Dunces. My own attempt in The Laughter and in Intemperance, is to present Seattle to readers. Seattle lends itself to delicious satire, with its touching self-belief of being unshakably progressive.

I am especially excited to see a wave in which a blend of self-satire and social commentary will be exploited by more writers with marginalized identities.

In satirizing academia as a setting, of course, we have unforgettable examples, from Richard Russo’s Straight Man to Zadie Smith’s On Beauty to one of my favorites, Mat Johnson’s Pym, in which Johnson blends satire and fantasy and follows Chris Jaynes, a Black literature professor obsessed with the work of Edgar Allan Poe who leads a crew to Antarctica seeking the mythical island of Tsalal, where he finds a world of “shambling white horrors.”

I am especially excited to see a wave in which a blend of self-satire and social commentary will be exploited by more writers with marginalized identities. In Counterfeit, for instance, Kirstin Chen gives us a caper story of Asian American young women on the wrong side of the law, but also a satirical take on the model minority myth in America. Jason Mott, in People Like Us, gives us a character who is an author like himself and who provides dark wit even as Mott critiques contemporary perils such as gun violence, racism, and collective grief in a time of alienation. Alejandro Varela, whose wry humor in The People Who Report More Stress gave us unforgettable queer and straight characters battling corrupt systems such as corporate America, racism, and gentrification, returns with Middle Spoon, a satirical queer love story with heartbreak and hope.

This brings me to a potential element of therapeutic processing that can be enabled through fictionalized self-satire. I found writing Intemperance to be cathartic for me, of course, but am pleasantly surprised by the expectation of catharsis in friends who have heard me speak of the novel. Damn, I can’t wait to start laughing at myself, one of them said.

__________________________________

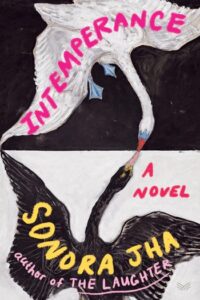

Intemperance by Sonora Jha is available from HarperVia, an imprint of HarperCollins.