Librarians are on the front lines of history and current events, when news and change arrive at a furious clip that only quickens every day.

Article continues after advertisement

And without libraries, my work would simply not exist.

I was a child who read books. There’s a picture of me, not quite a year old, in a blue sailor suit and a red ribbon tied around my neck, staring avidly at a picture book. I couldn’t have been reading yet—that wouldn’t happen until I was close to three, still plenty precocious—but the devotion was already there, the calling always present. I would always prefer reading to pretty much anything, whether it was practicing piano, doing homework, playing sports, and chores.

Books were everywhere as I grew up, and I know how fortunate I was. All around the house, because my parents and older brother were avid readers, too. In the sprawling home of my great-uncle, who spent many years as a sales representative for Harper & Row—before it was absorbed into HarperCollins, now my own publisher—and the duplex townhouses of my grandparents.

Going to the library was special, though. The elementary and high school ones, staffed by people who understood what books meant to kids because they’d never lost sight of what books meant to them. The local branch, a few minutes’ drive from my home, where I borrowed countless books at every age and had my first formative experience with microfilm—and no matter how many times I have used it, I still need to ask a librarian for help. The flagship location in my hometown, with its brutalist architecture, piles of newspapers threatening to burst out of the shelves, and the abundance of books in every genre—particularly crime fiction, my first and still greatest love.

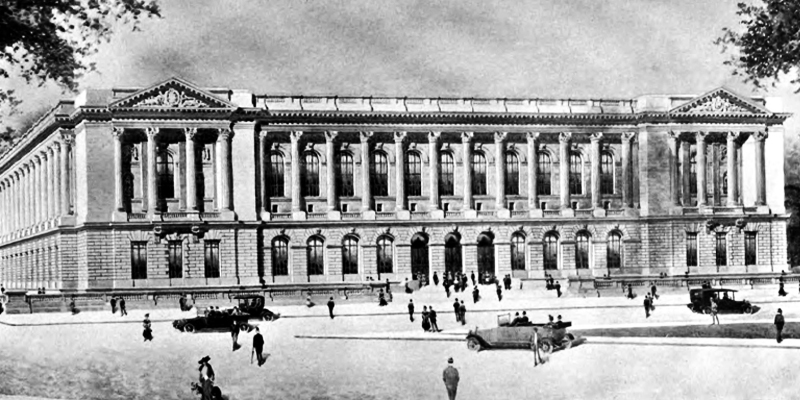

The university one, where not only could I request any book I needed for research—for class, and also my own—but I discovered the almighty power of the Lexis-Nexis database. And, when I moved to New York more than two decades ago, the magisterial 42nd Street Public Library, those twin lions beckoning visitors to climb up the stairs and partake of its treasures.

The wonder and thrill of the library hasn’t gone away for me, not at all, but it has certainly evolved in adulthood. I have come to know so many archive repositories, sifting through collections of authors, editors, and other luminaries as part of my research for three nonfiction books, several anthologies, and other journalism projects. Some of the institutions whose work I have benefited from enormously, visiting in person or requesting digital reproductions, include the Sterling Library at Yale University; the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; the New-York Historical; city and state archives in New Jersey, Oregon, Maryland, New York, and right here in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library.

The wonder and thrill of the library hasn’t gone away for me, not at all, but it has certainly evolved in adulthood.

And it was at Columbia University’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Library in early 2016 that I experienced one of the most transcendent experiences of my working life. I’d arrived to look at a selection of letters by the book editor and translator Sophie Wilkins, and what I thought would be anodyne correspondence between an editor and her author—the convicted murderer Edgar Smith—turned out to be anything but, altering the scope and trajectory of the project that would become my second book, Scoundrel. The excitement I felt at reading what perhaps three others—Sophie, Edgar, and the librarian cataloging the material—that I could not express in public, but could convey in book form, was like nothing I’d ever experienced.

Libraries and archives hold so much knowledge within their sacred confines. I will never lose sight of the awesome responsibility for those tasked with curating, maintaining, and presenting the information so that researchers and authors like me can make meaning of these documents. The librarian is a seeker and keeper of truth, and that makes her a dangerous figure in the eyes of those who fear the fullest, most comprehensive, and most uncomfortable truths emerging.

The librarian is a seeker and keeper of truth, and that makes her a dangerous figure in the eyes of those who fear the fullest, most comprehensive, and most uncomfortable truths emerging.

This is as precarious a moment as I’ve experienced in my own lifetime. Book bans accelerating at a pace that beggars belief. The unjust firing of Dr. Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress. The onrush to embrace generative AI without considering the consequences. And just yesterday, a terrible Supreme Court ruling that threatens to upend what books are taught in schools and available in their libraries.

It is a lot to absorb, but librarians have had so much practice at being buffers between vulnerable visitors and the might of an overreaching government, at state and at federal level. We saw this after the September 11 attacks when the Patriot Act gave carte blanche to the government to obtain patrons’ library records, and librarians stepped up to hold the tide, often at great personal peril.

And we’re seeing it again today.

It can seem overwhelming, I know. I feel it, too, with every shocking event we become accustomed to, every flouted law that becomes routine, every voice who landed here looking to better themselves silenced through deportation, detainment, and worse.

But every victory, however small, adds up. Every way something rolled back is reinstated is a sign that nothing, not even malevolence, is forever. Every time people gather together in community, be it a protest or bake sale, a house of worship or a house dance party, a bookstore or a library, something better and more beautiful blooms. Every piece of news imparted by organizations like the Freedom to Read Foundation, PEN America, and Authors Against Book Bans, of which I am a proud member, gladdens and heart and lifts the soul.

Let me leave you with the words of Molly Ivins, one of the sharpest columnists of the 20th century, who had this sage advice in the spring of 1993 that feels like the clarion call, and the confirmation, of what librarians across the country are doing every single moment:

“So keep fightin’ for freedom and justice, beloveds, but don’t you forget to have fun doin’ it. Lord, let your laughter ring forth. Be outrageous, ridicule the fraidy-cats, rejoice in all the oddities that freedom can produce. And when you get through kickin’ ass and celebratin’ the sheer joy of a good fight, be sure to tell those who come after how much fun it was.”

A good fight begins with books. A good fight begins with all of you.

–Keynote address at the American Librarian’s Association annual convention, June 28th, 2025