Gráinne O’Hare Considers the Power of Female Friendship Forged in Close Quarters

In the latter half of my twenties, I lived with a fellow postgrad I met through a mutual friend. We got on well from the beginning, and five years of living together (plus the crucible of various lockdowns) led to her becoming one of my closest friends. After finishing her PhD, she started applying for university jobs in other cities. The Hunger Games nature of the academic job market meant the pickings were slim and the chances of success were even slimmer, but after years of being at the same institution she wanted a change, a new challenge, and perhaps not to have to spend hundreds of pounds and hours of delays every time she wanted to visit her London-based boyfriend. I understood and agreed with her, but at the back of my mind I wondered what it would mean for me.

Article continues after advertisement

My own boyfriend and I had already talked about living together, and he suggested that if she moved out, he could move in, but I didn’t want to live at that flat with anyone but her. It was the home where we’d binged the whole of Desperate Housewives in lockdown; the home we’d stumbled back to after the pubs opened again, numb from negronis and outdoor seating; the home where we texted each other from our beds and I’d sometimes hear her from two rooms away, laughing out loud when she read my message. I didn’t want to live there without her.

I realized I wanted my characters’ mouldering rented house to be a cornerstone of the novel, a site of shared memories that made them feel by turns nostalgic and haunted.

My first novel is about friends living together in their twenties and early thirties, three women struggling to decide whether to keep living in the crumbling house they shared with their late best friend, or whether to let it go. This dilemma was inspired during lockdown, when my flatmate was listening to the audiobook of Bleak House. It is forty-three hours long and narrated by Miriam Margoyles, with whom it felt like we lived for several weeks as she accompanied my flatmate in the shower, cooking dinner, or hanging laundry. We watched the BBC dramatization together and I realized I wanted my characters’ mouldering rented house to be a cornerstone of the novel, a site of shared memories that made them feel by turns nostalgic and haunted.

As my flatmate sent off more and more job applications, I accepted that I would have to start looking for another place to live. Once I did, things moved quickly. Every time there was a new development—viewing a flat, sending the holding deposit, signing the contract—I didn’t want to talk about the fact that it was actually happening, so I dropped these details into conversation with my flatmate as flippantly as mentioning we needed to buy toilet paper. I did not cope well with the increasing likelihood that I would be the one to leave first. I kept hoping she would announce one day that she’d been accepted for a job and was moving out too; but she had started receiving rejection letters from the universities she’d applied to, and soon she was talking about a PhD student who was relocating to the city and might be able to take my room when I left.

When I told people I was moving in with my boyfriend, they went straight to delight and congratulations, which were nothing but well-meaning, and which irrationally got under my skin. I found myself wishing that the thrilled reactions would be followed up with more solemn questions about how it felt to be leaving my home of five years, about the strangeness of uncoupling my daily life from that of my flatmate, even though we would still live in the same postcode. The only person who ever did this was the friend who first introduced us, and when she asked I almost burst into tears.

Our landlord came round to organize the new tenancy agreement with the student who was moving into my old room, and he handed the pen to me and asked me to sign, explaining that someone else needed to be on the contract as a witness. My flatmate joked that it was like their wedding and our divorce at the same time. We made all the requisite Rachel and Monica references to it being “the end of an era.” My boyfriend and I got the keys to our new flat, and I shifted boxes and bags into the boot of his car and tried not to cry at the sight of my slowly-emptying bedroom. At the new place, I tripped by the gate and dropped my coffee cup on the pavement; it smashed and I started sobbing. Even though I was happy to be moving in with my boyfriend (who is extremely funny and hot and owns some very nice furniture), the idea of not living with my flatmate anymore was breaking my heart.

Talking and writing about those times reminds me why I write about friendships: because mine have been some of the most long-term and deep-seated loves of my life.

For nine months, I went to my old flat as a visitor, trying not to notice that there was a stranger’s laundry hanging in the living room and trying to resist the urge to peer into my old room to see what it looked like. In the spring, my friend was offered a job in a city an hour from London. The night before she left, I went over and we sat in the sunny back yard, on garden furniture that had blown away in a 2019 storm and had been returned to our back door by persons unknown over a year later. We reminisced about the fever dream of lockdown and the challenges of going back out into the world and trying to be people again. They were hard times, but I can’t imagine anyone else with whom I would rather have weathered them. Talking and writing about those times reminds me why I write about friendships: because mine have been some of the most long-term and deep-seated loves of my life.

I passed the flat on the bus a while ago and saw the front door had been repainted, a sleek black coat covering the fading terracotta. The flat itself was never particularly special; it was damp, cramped, dark. The sofa was so collapsed that getting up from it felt like core strength training. The gap under the back door meant the kitchen had an Arctic climate in the winter and a slug infestation all year round. We were woken in the night by trapped air hammering against the aging boiler, by the burglar alarm screaming after a power outage, by our student neighbors thundering home to the flat upstairs and partying into the small hours. Even so, I loved that flat. It was where I made a lot of mistakes and a lifelong friend. It was where I grew up. It was home.

__________________________________

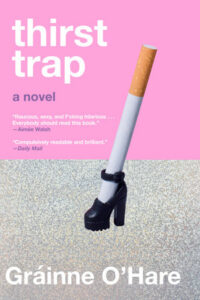

Thirst Trap by Gráinne O’Hare is available from Crown, an imprint of Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House.