Thomas Flett relies upon the ebb tide for a living, but he knows the end is near. One day soon, there’ll hardly be a morsel left for him to scrounge up from the beach that can’t be got by quicker means at half the price. Demand for what he catches is already on the wane, and who’s to say the sea will keep on yielding shrimp worth eating anyway. There’s all sorts in the water now that wasn’t there when he was just a lad. Strange chemicals and pesticides and sewage. Barely a few weeks ago, there was a putrid fatty sheen upon the sand from east to west; a month before, he waded in a residue of foam that reeked of curdled milk as he approached the shallows. Fleeting things, but if you’re asking him, they augur trouble – it’s been hard to sleep of late. His dreams are full of slag heaps made from rotten shrimp, and he’s there in amongst them with a shovel, trying to clear a path.

It’s five o’clock or thereabouts. He rises with the sky halfdark between the junction of his curtains, weary with the aches of yesterday. The sea-clothes he peeled off when he came home are slung over the chair beside the open window for an airing: his wool jumper, oiled and mangy at the chest from the persistent wiping of his hands; his trousers patched

up at the knees; a shirt gone vinegary beneath the armpits. But no matter. Who’ll be sniffing him except his mother and the horse?

He wears clean long-johns and a fresh white vest to balance out the stink; his ma has folded them so small and neat inside the drawer that he could slide them into envelopes and post them back to her. It’s Thursday, so a hot bath will be taken when he gets back home this afternoon. A nip or two of brandy will be needed afterwards to dull the sting of his exertions. Sleep should follow then, till suppertime at least.

*

At this hour, it doesn’t take too long to reach the landing at the beach. Fifteen minutes, riding on a curve until the unpaved track behind his cottage joins with the straight line

of Marshbank Road, when there’s a sudden clamour as the horse’s shoes clip on the tarmac, a soft rubber whoosh from the cart’s tyres, and all the disparate houses start to bunch

together on both sides, with shopfronts on the corner of each block presenting wares that tempt him into yearning for the things he can’t afford: good leather boots, a proper shaving

brush, a nice wool suit, thick books with gleaming covers, new LPs.

In his grandpa’s day, the shankers all rode out in a procession: twelve carts clopping down the promenade, their horses making such a din it could be heard above the ring of church

bells. All those fellas have retired or moved away, and some are in the ground at St Columba’s graveyard. He’s the only shanker left in town who’s steadfast to the old ways. There’s more profit to be made by using motor rigs and shrimping further down the coast near Broughton. Motor rigs can trawl a pair of ten-foot nets in deeper waters than he’d ever risk a horse in, catching four or five times more than he can manage. There aren’t so many sinkpits to be wary of up there. The beach is sheltered by the dunes. The rigs have custom-fitted boilers on their decks so they can cook the shrimp on board and skirt around food safety regulations, too. His ma – great schemer that she is – thinks he should get a bank loan to upgrade his operation: buy a scrapyard lorry chassis and an engine, add

the shed and boiler with a bit of help from a mechanic. But he doesn’t have that sort of motivation. He’s no empire builder. He’s accustomed to Pop’s methods and he won’t relinquish them so easily. Those ugly rigs are prone to rust, and, if you’re asking him, they’d be a waste of money – neither boat nor building, more like someone’s outside privy put on roller skates and given a big, panting motor. No, he’d sooner give up shanking altogether than succumb to using one of those.

The promenade is always free of traffic early in the morning. Wind is hurrying the sand along the gullies of the road. In summertime, Longferry is a town where people seem to

go on purpose. There’ll be day-trippers parading arm in arm here, come July, great lines of coaches parked up in the laybys spilling hordes of pensioners in sandals, giddy children

dripping ice cream from their knuckles. This is when the shanking season’s over and the shrimp are left to breed. It’s someone else’s playground then, and he can take or leave it. But in early March, it’s just another dismal place that folk can pass through on their way to somewhere more appealing, and the beach is where they stop to let their dogs run round.

He brings the cart down to the landing ramp and rides on a diagonal. To the north, the long legs of the pier, aglow with lanterns; to the south, the shores of Broughton and a stretch of grassy dunes receding into marsh. If he hadn’t traded in his watch, he’d check how long until the water starts to rise again, but it’s not hard to reckon it by sight when you’re accustomed to the job.

For now, the sea is just a faint grey runnel, two and something miles away. He rides on undulating sand that gives beneath the wheels as readily as butter. Biting wind and mizzle on his face. There’s no one else to talk to but his horse, who cannot answer back, and wouldn’t say a thing worth hearing if it could. Great whorls of steam rise from its flanks as it goes trudging on, the rattle of the harness making accidental music. He keeps his eyes trained on its shoulders, heedful of the slightest change in its behaviour or its gait. There isn’t any sureness to the ground hereafter and no promise that a hoof will not land false somewhere and drop. A draught horse could be seventeen or eighteen hands and it might still find trouble in the channels of Longferry. There are sinkpits all across the beach, if you go far enough to reach them. They can drag your horse down by the fetlocks till it cannot move, and if no one is there with you to pull it free, you’ll have to cut the straps and leave it there to drown. It happened to his grandpa half a dozen times in nearly sixty years of shanking. There’s no sense in getting soft about a horse when you’ve been raised on tales like that.

Even in the best of weather, it’s infuriating graft. He knows that he’ll be out here on his own for a few hours, drudging with the seagulls in his ears and shitting on him from above, repeating the same motions as the countless days before. It bores him worse than it exhausts him. Now and then, he’ll let his mind stray, whistling out a tune or coming up with different verses for ‘The Jolly Waggoner’, but when he’s less attentive to the job, mistakes can happen: like a decent catch escaping from his nets because he didn’t tie the dadding lines up tight. That’s just the sort of thing that costs you time and money, gets you scolded by your ma when you return with nothing for the coffers, and she won’t be shy reminding you of how you failed her. If your concentration goes out here, you’re at the mercy of the unexpected. Habit’s all you can rely on.

Now he’s out a mile from where he started, give or take, and he can see it up ahead_– the sea’s white lip, another mile away. The sight of it is more familiar than the wisps of his own breath upon the air. It never used to foul his mood this much, the cold, the loneliness, the graft, but that was long before he harboured any aspirations for himself besides what he was raised to want. He used to think it was enough to fill the whiskets up with shrimp each morning and accept the cash for them by afternoon. Providing is surviving – that’s what Pop would tell him, and what else should any man desire? Perhaps a wife, if he could find one that’d have him. Roof above his head. Big pantry cupboards stocked to keep his loved ones fed. A special drop of brandy now and then, and evenings in the pub. Well, surely he could do no better with his life than that? Except, these past few years, he’s come to understand: he settled for too little. Everything he puts his mind to when he isn’t on the beach – rehearsing songs on his guitar and rearranging them – that’s when he feels most alive, that’s when he’s at his best. If you were to put him in a league of great cart shankers, he’d be rooted to the bottom. Not a soul will ever look at him and think, My God, that fella catches shrimp so well, it takes my breath away – he’s very sure of that. But soon he’ll muster up the nerve to walk on to that little wooden stage inside the Fisher’s Rest, and he’s got confidence they’ll put their pints aside and listen when he sings. They might just clap and cheer and tell him afterwards: We never knew you had it in you, lad.

__________________________________

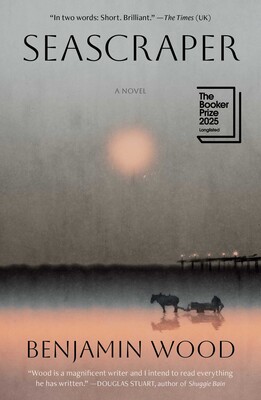

Excerpted from Seascraper by Benjamin Wood. Copyright © 2025 Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC