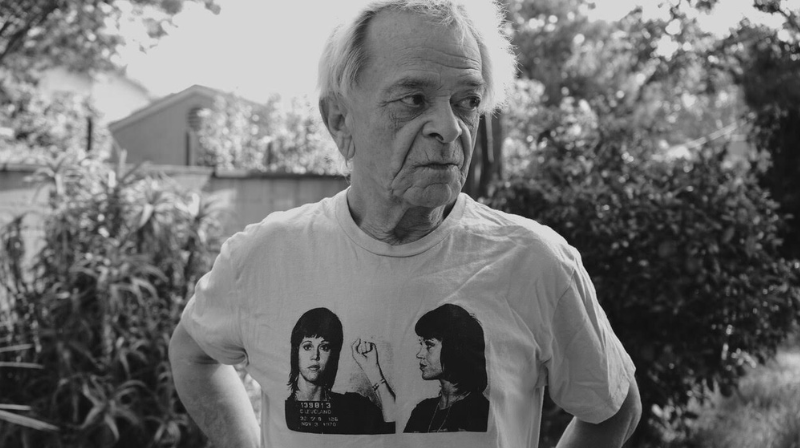

At the time of Gary Indiana’s death on October 23rd, 2024, the writer was at work on several new projects with both his current publishers, Semiotext(e) and Seven Stories. Here Hedi El Kholti of Semiotext(e) and Dan Simon of Seven Stories reminisce about Indiana’s late renaissance, the role his publishers played, and on Gary as a friend.

*

Hedi El Kholti: After Last Seen Entering the Biltmore, Gary’s collection of plays and short story came out in 2010, I remember Gary talking about how depressing it was for him that all his books were out of print and he asked me if we could republish them. I wanted to start with Horse Crazy. I loved that book and copies were scarce. I was more hesitant about the true crime trilogy because there were still a lot of copies in circulation and you could find them heavily discounted on Amazon. But Gary wanted to start by reissuing the crime trilogy. He told me it was the work he was the proudest of. So that’s what we did starting in 2015.

Dan Simon: They are amazing, pioneering works—demented psychological thrillers that are also deeply human stories. You began the process of the rediscovery of Gary Indiana, and I do think that after we came along a couple of years later, around 2016, Gary started to find something with the two of us that was pretty amazing—a writer of the 1980s and 1990s who became a force in the last decade of his life, basically from 2015 until his death in late 2024.

HEK: After the High Risk relationship [High Risk had published Gone Tomorrow and Rent Boy in 1993 and 1994; the imprint was shut down in 1997], his work didn’t have a context—other authors he had an affinity with. The crime trilogy had come out from different publishers originally. He didn’t have an agent any longer. He started to have health problems. Starting as far back as 2006, he got interested in what we were doing at Semiotext(e). He wrote a beautiful introduction for our publication of Pierre Guyotat’s Coma, and the same thing happened with him later at Seven Stories. Gary only read what fascinated him. So what happened with Gary and Semiotext(e) and Seven Stories is that he found a context again. Not long before he died, he wrote me a long email about some books we were publishing. When he stayed with me in LA, he’d read everything on my desk.

DS: Absolutely.

HEK: Both Semiotext(e) and Gary had installations in the 2014 Whitney Biennial. Around that time he wanted me to help him find a gallery in LA to give him a show. A beautiful and vibrant space, 365 Mission had opened a couple of years prior. It was a collaboration between Laura Owens, Gavin Brown, and Wendy Yao who had a bookstore in the space. I had a meeting with them and proposed a show of Gary’s work with a symposium around his books to coincide with the republication of the first title of the crime trilogy. His memoir, I Can Give you Anything but Love, was coming out around the same time with Rizzoli. A couple of weeks before the opening there was a launch of the memoir at Skylight which had a very sparse attendance. I had this sense that young people didn’t know about Gary Indiana’s work. But the Symposium was packed and I think that was the beginning of the rediscovery.

DS: There was a young writer working at Seven Stories named Noah Kumin. For a time he was hanging out with some of the same crowd as Gary. In 2016 he brought me Horse Crazy, Gone Tomorrow, and an essays project that would eventually become Fire Season. I took Horse Crazy home with me and read it over the weekend, and I was amazed. It felt like a major personal discovery. I know a great book when I come across it. I was kind of shocked—and happy. This novel of obsession, with the AIDS epidemic in the background, but where AIDS is never mentioned, a passionate book about people and the city in all its innocence and desperation.

I had had this experience that I have never had before, at least not in the same way, of someone who always gives more than is asked of him, no matter what. And that in a nutshell is who I think Gary was.

HEK: He talked to me about it, asked me if it was okay if he did Horse Crazy, which we originally wanted to publish, with Seven Sories. And I encouraged him. I knew you a little, and you had published my friend Abdellah Taïa. I thought there was a chance you’d make things happen for him in New York.

DS: And it kind of did happen that way.

HEK: Yeah. You know, we did a lot of work in that decade to get Gary read by people. So it was really a combination of him having our two publishing houses behind him at the same time that brought him back.

Dan: I hadn’t thought about it in this way before, but I think you’re right.

HEK: People like to call him “acerbic,” but I never heard him say a mean word about you or me, or SSP or Semiotext(e).

DS: Yes, we both protected him and loved him, and he was very protective and loving of us both. He used to say you were his best friend, he said that often actually.

HEK: He didn’t like to be fucked-with, but he was very happy when he was treated with respect. I found him an apartment in LA after the symposium and we spent quite a lot of time together.

DS: Initially, Fire Season was going to be a straight reprint of an earlier essay collection he had done at High Risk / Serpent’s Tail called Let It Bleed, with a few new essays added. But what happened is that he kept telling me to add essays that he’d published in the meanwhile. And before long the book was mostly completely new material. And he didn’t stop there, he just kept going. “Christian Lorentzen has to write the intro.” “Sam McKinnis has to do the cover.” And by the time we were done I had had this experience that I have never had before, at least not in the same way, of someone who always gives more than is asked of him, no matter what. And that in a nutshell is who I think Gary was.

HEK: I had a very similar experience—especially in the last six months. We were working on a collection of his columns from the 2010s—mostly from Vice. Vice was closing down back then, so I saved them all. And I read them, 26 in all, from Vice alone, really good in the moment and even better now in retrospect. He was mixing in what was going on, say the PEN protests, with what has happening in his own life. So Gary was giving me leads to where he’d placed pieces. And then he’d find other ones—in his phone or on his computer, pieces he’d done for Bookforum or other places, some very different in tone. He’d say, “Let’s add this—and that.” And then he’d say, “I’ve got all this other stuff that I wrote for Art in America.” So we ended up conceiving two different books. One solely with the columns and diary pieces and another one with uncollected essays. For the columns he was feeling that this was a moment, maybe the last moment in the culture, when he felt he could speak up freely and write with a certain authority without fear of being ganged up on in some corner of the internet. He felt it wasn’t worth it any longer.

DS: How do you feel about all the attention since Gary died?

HEK: It’s bittersweet. He used to joke about what would happen when he died: “You’ll see, a lot will happen when I die.” To Gary it was a sign that people did not want to give him certain kinds of attention when he was alive.

DS: The New York Times obituary seemed to want to keep him in the margins. I mean, it was long and very prominent, but touched on things I think would have made Gary wince.

HEK: To them, the biggest thing was his role of art critic for The Village Voice. He would say to me, “I’ve been trying to leave that behind me for 30 years.” People constantly wanted to put him back into that ‘80s moment—and the Times obit represents an example of that. A very dark time he wanted to leave behind. You just have to read the last column he did for the Village Voice, “Vile Days,” to feel the dark psychic atmosphere on the late ’80s in New York. He desperately wanted to leave behind.

DS: Gary was under contract with us for his next novel when he died, and working hard on it, always more interested in the present and the future, not in the past.

HEK: Besides Horse Crazy, my other favorite among Gary’s novels is Do Everything in the Dark

DS: I believe that in the years ahead a lot of people will have that explosive sense of joyous discovery when reading Gary Indiana for the first time that we both had with Horse Crazy and Do Everything in the Dark.

*

Hedi El Kholti is co-editor at Semiotext(e), creator of Animal Shelter, an occasional journal of art, sex, and literature, and founder of the Intervention Series.

Dan Simon is founder and publisher at Seven Stories Press. His debut novel, Ashland, will be published by Europa Editions in February 2026.