This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

I started writing The Good Mother Myth the summer my kids turned 3 and 5, when I woke from the exhaustion of early motherhood enough to begin to grapple with what had happened to me in those years. How was it possible to love my kids so much and also feel so totally ruined by the labor of caring for them? Instead of sliding from an easy pregnancy into a blissful postpartum, I found myself wracked with what I can see now was a pretty significant case of postpartum anxiety. It would be years until I learned that term and immediately saw myself in the symptoms. Instead, the rage and sleeplessness and deep loneliness I’d felt in those early months seemed simply like proof that I was a bad mom.

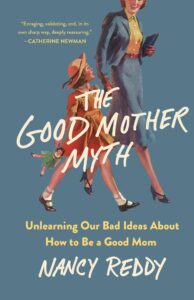

I wanted to write a book that would help me unpack that experience. By then, I’d published my first book of poetry and written a scholarly dissertation, so I knew something about writing from memory and writing from research. But this new book, I knew, wanted to be something else. I didn’t know much at all about either the craft or business of nonfiction, didn’t yet know to reach for the terms narrative nonfiction or memoir plus, but the project was calling me.

That summer, I had a weeklong residency at a little farmhouse in Tennessee, and I got to work writing everything I thought might go into the book: the body horror of early breastfeeding, the afternoons I spent crying in a dark room when the baby howled instead of napping, the long walks through our leafy neighborhood where I watched the baby come into the world and flap his hands as shadows passed over him. I typed up everything I was learning about maternal ambivalence and postpartum anxiety, all my questions about mothering across time and in other cultures. At the end of that week, I had 20k words in a Scrivener document and a real sense of excitement and momentum.

At what moments had I understood something new or shed a bad idea? Those aha! moments often ended or began a chapter, and driving toward them gave the book its shape.

When I went home and kept working, though, I came to an alarming realization: you can’t sustain a full manuscript on finely-wrought images and quippy takes on shoddy science. No matter how beautiful the language or moving the metaphors, no reader was going to stick with me for 80k words of lyrical weeping in the dark. I was writing about my own life, but I still had to find the plot.

I found the answer to that problem in a surprising place. John Truby’s The Anatomy of Story is a quirky book—he’s really into Tootsie, and he notes early on that “I’m going to assume that the main character is male, simply because it’s easier for me to write that way”—but it provided me with the framework I needed to turn those scattered scenes into a coherent narrative.

The first task, I learned, was to define the main character in terms of desire, weakness, and need, terms Truby uses to distinguish between a character’s ostensible goal and their deep psychological journey. The way Truby defines it, desire is your character’s conscious goal, “the driving force in the story, the line from which everything else hangs.” Need, on the other hand, is “subterranean,” something the character is not even aware of as the action begins. The character’s need is connected to their weakness. Truby gets a little dramatic here, but I think he’s right: this weakness means that at the beginning of the story, “something is missing within him that is so profound, it is ruining his life.”

I spent weeks wandering around, thinking back to my early months of motherhood and asking myself, what did I want? My desire was to be a good mom, which for me meant turning myself into the kind of babywearing, breastfeeding, cloth-diapering good mother I’d assumed I’d seamlessly become. My need took me longer to figure out. It took years of reflection and research and deep conversations with friends and family (and some actual therapy, along with the quasi-therapeutic work of writing) to realize that what I’d needed was to let go of those ideas of goodness and figure out for myself what kind of mother I wanted to be. My weaknesses are too many to name here, but central to the story was my belief that I could just research and white-knuckle my way through any challenge on my own. Once I’d identified those key elements, I wrote each one on an index card and taped it on the blank wall in my office. (Another item to file under: writing memoir is embarrassing.)

Truby starts with desire, weakness, and need because he’s interested in complex fictional characters with deep motivations and weaknesses that will propel the story. But I think these elements are just as essential for memoir. The most moving memoirs are the ones in which you see someone transformed.

For a writer, this can feel risky. You’re going to have to let the reader see you at your ugliest and trust that they’ll stick with you for the transformation. A favorite example: Claire Dederer’s Monsters, which starts by considering the art of monstrous men but takes a turn at the center to consider the ways in which Dederer herself has been monstrous, works only because she’s let us see some really bad behavior from the beginning without apology or even much commentary. In an early draft of my own book, following a long paragraph that described the various things I’d excelled at and how sure I’d been that I would carry that record of accomplishment with me into motherhood, I wrote a marginal note to my editor: can a reader tell I know I’m being kind of unbearable here? I wanted to insert a wink into the text, but I held back. That irritating, uptight person on page one was part of the story, and I had to let her be.

*

Plot is most obviously a matter of time: what time frame will the book cover, and how long will you spend on each event during that time? But plot is also tied up with place: where will you take your reader, and what will they find there? Truby describes this as “story world,” by which he means not just the literal place, but also the texture and feelings of that place and how those details connect to the big ideas of the book. For me, this concept of the story world really came together when I read Truby’s insistence that the writer define “the arena of the story,” or the specific physical place that would contain all the action. My book was set in Madison, Wisconsin, where I’d been a grad student when my kids were born. Madison was also home to a central strand of the book’s research, because Harry Harlow, a psychologist whose research on maternal attachment in infant monkeys is at the center of attachment theory, spent his career on that same campus, decades earlier.

Thinking about story world helped me clarify the kinds of details I needed to include about Madison, which in my telling is a city of farmers markets and sidewalk cafes and bearded babywearing dads shopping at the co-op. Considering my story and Harlow’s together told me how and where to start at end the book: at the zoo, where I’d spent countless hours with my toddler, including the afternoon late in my second pregnancy when I came across a very-pregnant orangutan on labor watch and felt a deep kinship with my fellow primate. Harlow, too, had begun his work in the zoo, doing experiments in learning with orangutans and a baboon before he had a proper primate lab on campus. Once I knew the book would begin and end at the zoo, I had a frame for the book. This one place stitched a major research strand to the overall narrative.

The zoo gave me a narrative framework—the book would span the two years between my first son’s birth and my second—but I still needed a plot. I’ve read many explanations of three-act structure. I have drawn plot charts in my notebook and mapped them out on the blank wall beside my index cards of need, desire, weakness, and all the scenes that might make up a plot. Despite all that diligent studying and outlining, I’m not sure I’ll ever fully understand the “act” structure or “beats” that novelists talk about. What worked for me, in thinking about my own life, was focusing on crucial turning points—the aha! moments where I came to a realization or where I understood something new about myself.

Following Truby’s advice, I’d made a big list of possible scenes. Then, once I’d figured out the overall timeframe, I’d copied the scenes I knew I’d want to include onto index cards and arranged them on the wall. As I was shaping those scenes into chapters, the question that helped most was focusing on the moments that had been genuinely transformative. At what moments had I understood something new or shed a bad idea? Those aha! moments often ended or began a chapter, and driving toward them gave the book its shape.

Thinking of plot in this way—as movement toward revelation or deeper understanding, rather than just a series of events—was only possible after I’d gotten a handle on desire and need, as Truby defines them. Now, as I start working on a new book, about the history of our ideas of home, I’ve returned to my marked-up copy of Truby. What is my desire and my need? What problem is so great that it threatens to ruin my life? It’s a high bar. But it’s the best way I know into the story.

______________________________________

The Good Mother Myth by Nancy Reddy is available via St. Martin’s Press.