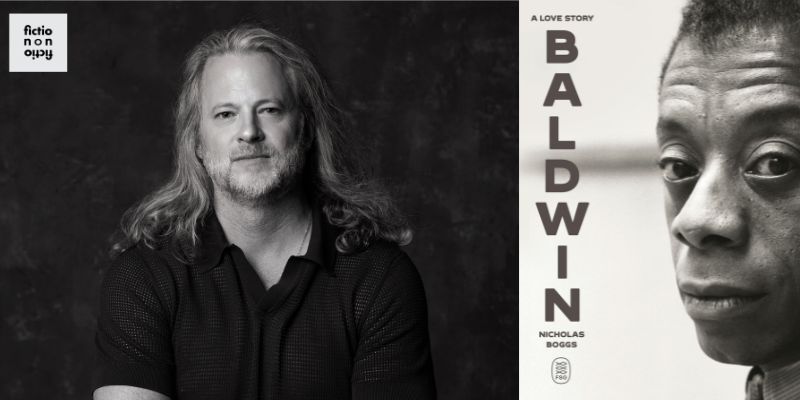

Biographer Nicholas Boggs joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss his groundbreaking new book, Baldwin: A Love Story, the first major biography of James Baldwin to be published in three decades. Boggs recalls how finding Baldwin’s only children’s book in a Yale library as a college student led him to track down the volume’s illustrator, the French artist Yoran Cazac, Baldwin’s last great love. He talks about interviewing people who had never previously spoken about their relationships with the iconic author, including Cazac, whom at least one previous biographer had wrongly guessed was deceased. Boggs reflects on the importance of considering Blackness, queerness, and chosen family as central to Baldwin’s life and art. He discusses Baldwin’s youth in Harlem, his years in Europe and Istanbul, and his relationships with the painters Beauford Delaney and Lucien Happersberger, the actor Engin Cezzar, and Cazac, as well as many others. Boggs considers how Baldwin’s deepest friendships and romances influenced his life and work, including Another Country, Go Tell It on the Mountain, Notes of a Native Son, and Giovanni’s Room. He reads from the book.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/ This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, and Moss Terrell.

Baldwin: A Love Story • Little Man, Little Man (ed.) • “They Will Try to Kill You”: James Baldwin’s Fraught Hollywood Journey | Vanity Fair • James Baldwin’s Love Stories | Vogue

“Open Letter to the Born Again” | The Nation • “If Black English Isn’t a Language, Then Tell Me, What Is?” | The New York Times • Giovanni’s Room • Another Country • Notes of a Native Son • Go Tell It on the Mountain • Everybody’s Protest Novel

Others:

James Baldwin′s Turkish Decade by Magdalena J. Zaborowska • James Baldwin: A Biography by David Leeming

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH NICHOLAS BOGGS

V.V. Ganeshananthan: One of the other things that book reminded me of was just how prolific Baldwin was. It also reminded me that one of his great ambitions and successes was as a playwright, and after Lucien [Happersberger], the next era in the book is marked by his connection to a Turkish actor, Engin Cezzar. Whitney mentioned Marlon Brando before, and Baldwin was dreaming of Marlon Brando playing opposite Engin in an adaptation of Giovanni’s Room. I think Giovanni’s Room was the first Baldwin I read so I was riveted by this part. Can you talk a little bit about Engin and the importance of Baldwin’s time in Turkey?

Nicholas Boggs: So, Engin Cezzar played the role of Giovanni and Baldwin met him at this Actors Studio workshop version of it. Engin was this crazy young Yale Drama School dropout who had been picked up by Marlon Brando’s agent to come to New York and study with Lee Strasberg. There was just an immediate connection between Engin and Baldwin. They supposedly cut their hands and mixed their blood to become blood brothers. They hung out and they also built a lifelong relationship. They had all kinds of dreams of working together in film and stage, but Baldwin eventually followed Engin to Istanbul in 1961 where he finished Another Country, and then he ended up basically living there for the rest of the ’60s. He came back for the civil rights marches and other important events and speeches. But he considered Istanbul his home, and he considered Engin and his wife Gülriz to be his family.

This is another example of Baldwin—he loved his biological family, and it was very important that he make money to help support them, and he had to create these alternative kinship structures when he was abroad. And Engin Cezzar was definitely one of them. Baldwin ended up directing this play, Fortune and Men’s Eyes, which was this homosexual prison play in a very socially conservative country. So they had an incredible collaboration, an incredible relationship, which had erotic undertones for sure, but as often happened with Baldwin, he was very able to move in between these erotic interests and these friendships, brotherhoods. He had a very expansive sense of how to relate to the people that he loved.

VVG: And a lot of the men with whom he was involved were married. They were not necessarily presenting as queer. So this mention of erotic undertones, Whitney mentioned that he wasn’t romantically involved with Beauford Delaney but there are hints that Beauford was interested in that. Lucien [Happersberger] and Baldwin part ways and then they come back together. It’s this really interesting porousness that seems to have fed him artistically in such an interesting way. And the years in Turkey—Baldwin in Paris is fairly well documented, but you’re one of the first writers to address this time in Turkey so directly, and you went there.

NB: I did. Magdalena Zaborowska has an incredible book that came out from Duke University Press. She really is the groundbreaking scholar on Turkey. But yes, I went twice. My research assistant is Turkish. I took it very seriously. I spoke a lot with Maureen Freely, who grew up in Turkey and Baldwin was around her all the time when she was a young girl, and they’d be at the parties. I fell in love with Istanbul myself. So I went there. I interviewed the surviving actors and people involved in the play, because Istanbul was absolutely a crucial period in American history. He really found it useful to be in this other place that allowed him to reflect back on America in these new ways. But he also just needed—he was really famous by that time, and he wasn’t well known there, but then the play was such a huge success that he was famous there. That’s when he had to go to the south of France to get away from the attention he was getting in that country.

VVG: I want to rewind a little bit to this mention of Brando, partly because I have always been fascinated by Brando and have read a little bit more about him. This was one of the many moments where I thought about how Baldwin’s loves were so many and you had to narrow it to these four. Here there’s this little hint that maybe Brando, maybe not. You refer to the “instability of the Brando0Baldwin archive,” and it’s this glimpse into some of the challenges of research. Could you talk a little bit about how you decided to write about Brando, what the limitations were, and how you ended up picking who you picked?

NB: Quincy Jones had said in New York Magazine that they’d had a sexual relationship. That was well-known as a rumor. Some other folks were giving me information that might maybe substantiate it. I remember Judith Thurman, the biographer, I told her about this, and she’s like, “Be careful. It would be just like Marlon Brando to enter a book and hijack it. You can’t let Marlon Brando take over the book.” But Brando was extremely important to Baldwin as a friend. He financed him at times early in his career. But Brando was also part of this fabric of same-sex relationships that Baldwin had on this continuum that did make writing the book challenging. I transcribed an interview that David Leaming did with Baldwin before he died where Baldwin told him that, yeah, Beauford wanted something with him early on but he didn’t push it. But there was always this interest, and it infused their relationship, because Beauford would get jealous when Baldwin had lovers. And then Lucien, because he married a woman and had children and was primarily involved with women, even though Baldwin was probably his great love, how do you write about this? How do you write about Brando when you don’t know for sure? It goes back to how this whole thing started with Yoran Cazac, reading about him in Leeming’s biography, not being clear what their relationship was, then slowly meeting him, interviewing people.

The big moment for me in terms of an archive “aha” moment was, I had known that they had actually had an intimate relationship, but I hadn’t really seen any physical evidence of it until 2018 when I went to Tuscany and Beatrice Cazac found this extraordinary, unpublished love poem “Saturnia,” which are these hot springs that Baldwin had gone to with Yoran, and she read it out loud to me, translating it back from the French into the English, because he wrote it in French, because Yoran did not speak English. It was just an extraordinary moment where I was like, “Okay, this is why these kinds of archival finds are so important.” And not that a love poem says, “Absolutely, this is what happened in their relationship.” But it gave such texture and detail to Baldwin waking up and thinking of him and reading his horoscope and wondering what he was doing. And it was really a full circle moment for me, when I was like, “Wow. I think I was always looking for this, for this moment, for this poem.”

VVG: Of course, this all leads to Little Man, Little Man being reissued in 2018. Earlier you were like “I was a junior in college and I just wanted to get this Baldwin classic back into print.” That is not what I was doing in my junior year of college. That’s an extraordinary project for a young writer to take on as the first thing they’re doing. Can you talk a little bit about that? Because the framing of love in that book, and Yoran Cazac’s relationship with Baldwin is how you ended up at this love story conception of Baldwin.

NB: This gives us this intimate look at how he thought and felt definitely, because the book is dedicated to Beauford Delaney, and it was Beauford who introduced Baldwin to Yoran Cazac. So you have this nexus right there. It was unconscious, I didn’t know what I was doing, I was so young. I knew that I was drawn to this weird little children’s book that wasn’t a children’s book, that was a children’s book for adults. I sensed that it contained a secret. I sensed that it had a history, and I wanted to bring it back into print. I sensed that there was a love story behind it. So it all grew out from there, but the process of getting it republished took decades.

Back then—and it wasn’t that long ago—the publishers were really confounded by the book, as they were when it was published. It was written in Black English. I think that was one of the major issues. And of course, Baldwin has this important essay, “If Black English Isn’t a Language, Then Tell Me, What Is?” So it was hard to get it republished, but Duke University Press was really visionary in this way. And my co-editor, Jennifer De Vere Brody, was really wonderful. She really helped me. She made it happen. I wrote my senior thesis on Little Man, Little Man, it was published, and she was a reader for the press that was published in. So I just kept following the trails that this book opened up. Basically, going over there and meeting him, meeting his wife, Judith Thurman was best friends with them, and was also the godmother to the son that Baldwin was godfather too. So every time I tried to get away from it and do something else, something kept pulling me back. Judith Thurman said to me 20 years ago, “You have to write the James Baldwin biography.” And I said, “No way. I’m not the person to do it. I don’t know how to do that. I don’t want to do that.” But she’s always right.

Whitney Terrell: You appear in this book, most notably in the section on Cazac. I’m a Baldwin fan, and have been influenced in my fiction writing by his fiction writing, and I love Another Country, and Go Tell It On The Mountain is one of my favorites. Reading your book, it seems clear that you have been changed as a writer and a reader by his work but you’ve read more of it and spoken to many more people and know more about his life than I ever will. How did the process of writing this book change you?

NB: It changed me as a writer. It made me a writer actually, because I discovered the book, and then that senior thesis was published, and I thought, “Oh, I’ll become an academic” even though I really thought of myself as a writer. And I got the PhD, and then towards the end of the PhD, when I was supposed to be writing an academic book, that’s when I met Yoran Cazac, and I’m like, “These are living people. I don’t want to write an academic book. I don’t know what I want to write.” I went and got my MFA after the PhD and I wrote a little bit of fiction. The way that it changed me was, the book forced me to transition into a writer of narrative nonfiction. At least at this stage in my life and career, that’s what this book called for, and that’s what it changed me into. I am happy about that. It was very laborious, and it took a long time but I also enjoyed telling a story, not just recording a life, but transforming it into a love story, into these love stories, because I could never have written it as a straight—no pun intended—but as a straight biography, cradle-to-the-grave just told in a standard way. That kind of book never really interested me as a reader either.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy. Photograph of Nicholas Boggs by Noah Loof.