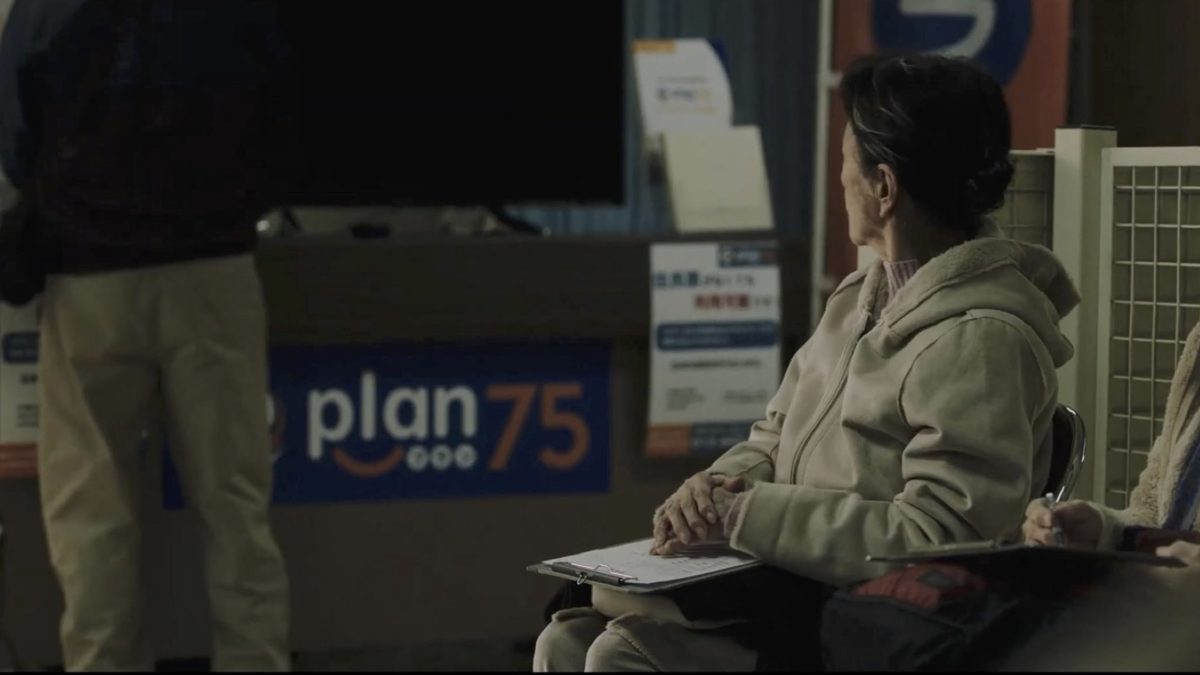

In an aging society, how can older people regain a sense of futurity? In Chie Hayakawa’s film Plan 75 (2022), a state-managed, voluntary program in Japan promotes euthanasia for anyone older than 75 years, regardless of health or fitness. While clearly reducing applicants to a number (age), the film also frames this “Plan 75” program as a chance (perhaps the only chance) to exercise agency over aging, and to be part of a larger “plan” for the future of the nation by relieving the economic burden of Japan’s super-aging society. Yet, as the story unfolds, we see that Plan 75’s shiny veneer is underpinned by sinister undertones of ageism and societal abandonment. Through characters like Michi—an older woman led toward Plan 75 after the loss of work and friendships—the audience confronts the chilling ordinariness of the social death, as well as the seductive promise of relief through assisted death. The film thematizes the fear of messier forms of “geronticide” by neglect, such as “solitary deaths” (kodokushi) and alludes to Japanese folktales of obasuteyama, the practice of abandoning old parents in the mountains to die, which have also been made into popular films. From a contemporary perspective, Plan 75 holds a mirror to current-day Japan, where incidents of such geronticide committed by family members experiencing “caregiver fatigue” take place, on average, once every eight days.

“Geronticide” (also referred to as senicide, gerocide, senilicide, or eldercide) refers to the practice of killing older persons. It is typically used to refer to forms of ritual or other culturally sanctioned forms of death hastening of older persons: ranging from violent killings to more widespread forms of dispossession, neglect, and abandonment as well as voluntary deaths (in which the older person asks to be killed). Does the term likewise apply to what gerontologist Raimund Pousset called the “silent deaths” of older persons, those that emerge from ageist cultural norms, legal institutions, and social structures? Do things like the increasing public support for assisted dying legislation or the institutional failures that led to mass deaths of older people during the COVID-19 pandemic count as “geronticide”?

In fact, the debates about medically assisted dying and institutional response to the COVID-19 crisis risk eclipsing our attention to both overt and more insidious forms of geronticide. Reexamining geronticide helps to sharpen our focus on what is at stake in debates about medically assisted dying, ageism, and disability. It means looking beyond tabloid headlines and courtroom investigations surrounding individual perpetrators’ character or intentions, and instead, interrogating the broader social conditions that render older people killable, not because they are weak and frail, but because they are already socially “dead.”

Geronticide,“Plan 75” warns, is not merely the act of ending life; when society denies older individuals their future, it is the erosion of humanity itself.

The modern loss of social roles and identity in later life, according to anthropologist Haim Hazan, constitutes “social death.” Similarly, aging studies scholars Chris Gilleard and Paul Higgs have argued that the social death of older people is part of a “social imaginary of a fourth age”: a period of life beyond the possibility of aspiring toward active, resilient, or “successful” aging. By placing older people outside the trajectory of social progress, this fourth age imaginary renders older lives stagnant and without forward momentum. Denied a future by which to orient and give value to their present life, they are further marginalized and easier to kill.

Geronticide—the killing of those without futures—is different from other forms of voluntary death of older people. For example, the voluntary suicide of older people in northern Siberia is understood within cosmological systems, wherein their “sacrifice” animates the future of vital relationships between community, land, and ancestors. In contrast, geronticide excludes an older person from futurity, whether through prisons or nursing homes, or through the internalization of social imaginaries of the fourth age that underpin these institutions. These forms of ageism are motivated by the neo-Malthusian fantasy of restoring a livable future by killing the old to make room for the young.

This concept of geronticide is at the heart of Hayakawa’s Plan 75, projected onto a speculative alternative present in Japan. This film resonates with other works of futuristic geronticidal dystopian fiction—such as the novel and subsequent movie Logan’s Run (1967 and 1976) by William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson, or Margaret Atwood’s short story “Torching the Dusties” (2014)—reflecting urgent ethical debates surrounding geronticide in contemporary society. Set against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, Plan 75 critiques the dehumanizing narratives that frame aging as an economic and social burden, and echoes real-life instances of ageist and ableist violence, such as the 2016 mass murder of disabled people in Sagamihara, Japan. By exposing the state’s role in assigning value to human lives based on productive futurity assumed solely based on age, the film challenges the moral and emotional toll of policies that treat older people as waste.

More importantly, Plan 75 illustrates how easily lives like Michi’s could be saved from the despair of geronticide, even through small yet profound acts of care and recognition. As the young workers administering the program interact with their older clients, they begin to see them as people, with value beyond their age-based futurity. Through the transformative power of intergenerational solidarity, the film advocates for dismantling the binary between old and young and fostering a culture where aging is not synonymous with isolation or decline.

In doing so, Plan 75 becomes both a cautionary tale and a call to action against ageism, urging society to value every stage of life as meaningful, interconnected, and worthy of care. Geronticide, it warns, is not merely the act of ending life; when society denies older individuals their future, it is the erosion of humanity itself. ![]()

This article was commissioned by Matthew Wolf-Meyer.

Featured image: Still from Plan 75 / IMDb.