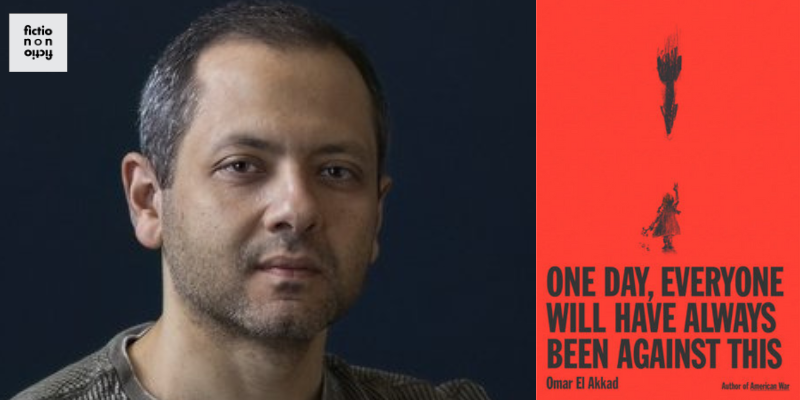

Writer Omar El Akkad joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss his recent nonfiction book, One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This, which was just nominated for the National Book Award in nonfiction. El Akkad talks about developing the arc of the book, which addresses how Israel’s genocide in Gaza led to his “breaking away from the notion that the polite, Western liberal ever stod for anything at all.” He explains how he conceptualized the West as a young man moving from Egypt to Qatar to Canada and finally the U.S. He also talks about how he can no longer vote for Democrats simply because they are “the lesser evil.” He reflects on how to talk to children about naming and understanding the world as it really is. El Akkad reads from One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/ This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, and Moss Terrell.

One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This • What Strange Paradise • American War • Omar El Akkad on Genocide, Complicit Liberals, and the Terrible Wrath of the West | Literary Hub • Omar El Akkad on X: “One day, when it’s safe, when there’s no personal downside to calling a thing what it is, when it’s too late to hold anyone accountable, everyone will have always been against this.”

Others:

Suzanne Nossel, PEN America Leader, to Leave Embattled Organization – The New York Times (October 31, 2024) • A Campus for All | Faculty & Academic Affairs (University of Minnesota) • Holocaust Scholar Raz Segal Loses Univ. of Minnesota Job Offer for Saying Israel Is Committing Genocide | Democracy Now! (June 18, 2024)

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH OMAR EL AKKAD

Whitney Terrell: You talk a lot about the Democratic Party’s response to what’s happening in Gaza in the book. Now the Democrats you’ll see online all the time are like “Well how do you like it now, you progressives who didn’t vote for Harris? You’ve got someone worse in office.” I thought that your arguments and discussions about why that isn’t useful, doesn’t make sense, or perhaps is worse than that, were interesting, and I wondered if you could outline those.

Omar El Akkad: I live in Portland, so I have this conversation a lot, and in fact, more so than any facet of the ongoing genocide. This appears to upset people in this part of the world to a degree that honestly, I don’t see otherwise. I make this clear in the book, I have no interest in telling anybody how to vote. Honestly, if you’re a member of a minority group in this country who’s genuinely terrified for their survival, as many people are, I’m not going to blame you for picking the lesser evil. I was that person for the vast majority of my life. You pick up the ballot. You see whoever has the R next to their name, and you vote for whoever has the D next to their name, because, hey, lesser evil. I think the argument I was trying to make is that almost everybody on this earth can only behave in a pragmatic, relativistic way for so long before they hit an absolute threshold, that there is an absolute ethical or moral line beyond which you simply can’t behave in that manner anymore. For me, obviously the last two years crossed that line. That’s evident by every page of this book.

But what has been really clarifying is that response you’re talking about. Because I remember getting those fundraising emails that were talking to me about how Donald Trump is an existential threat to the future of democracy. And then I remember not long after the election, watching the leaders of the same party that sent me those fundraising emails palling around with Donald Trump at Jimmy Carter’s funeral. I remember getting the fundraising emails talking to me about how climate change is an existential threat to human existence. And then I remember watching the leaders of the same party talk about how not only are they going to not impose a moratorium on new fossil fuel development, not only are they not going to do any of that, they won’t stop new fracking initiatives. That disconnect between the performance and the reality is just something that you essentially have to accept as a given if you’re going to continue with this endless allegiance to the lesser of two evils.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: You write very beautifully about, not only your own family, but also children in Palestine, and this uncrossable gap of when your own child is sick, there’s a holy devotion to the urgency that you feel around that, a single-mindedness, and that when it is your child, of course, you feel differently. And I can’t get people to—I’m sure I’m not the only person feeling this frustration—you can’t get people to imagine that those children are their children, which is just crazy-making.

OAE: It is crazy-making. Everything you’ve just described, I’ve both gone through in various forms, and also had people come up to me after after readings and describe their version of it. I think crazy making is the right description. I often talk about this idea that I am the angriest I have ever been over the last two years, right? You wake up every morning, you turn on your computer and you see the worst possible thing, right? And you know your tax money is paying for it. You know this, and you’re being told over and over and over again that not only is this good and necessary, but that if you try to stand up against it in any way, you’re the bad guy. However your listeners feel about this, I don’t care. I think I say in the book that I’m not interested in changing anyone’s mind about anything, but it’s difficult to describe the level of rage that I live with every day.

Yet I know and every event I’ve done— and I’ve now done hundreds, I’ve done hundreds of interviews for this book, if you add it all up, we’re in the triple digits—at no point does my voice rise above this, because I know full well that I can’t be the angry Arab guy, right? You can’t. The second you become that, the ceiling on what you’re assumed to be capable of doing becomes unlimited. So I have to be polite. Above all else, I have to be nice. And the nicest people I meet by a wide margin, the nicest, most civil, most polite, are the ones who are oblivious to the fact that any of this is happening. The angriest, most annoying people to be around are the ones who are fighting this tooth and nail because they have no choice. They can’t look away, and it’s making them angrier, and it’s making them more difficult to be around.

In terms of the other sort of crazy-making aspect of it, I know we’re on a trajectory, and I know where we’re headed. The book is titled what it’s titled for a reason, and one way or another, I’m going to be proven right or wrong. That’s going to happen right? But recently I had the new heads of this literary organization whose sole purpose is to protect writers and journalists and who have done a horrific job of saying nothing about Gaza. They got in touch, and they were like, “Look, we’re doing a listening session.” And, fine, okay. So we got on this meeting and then at one point I was like, “Listen, I don’t know what to tell you. I suppose if I had to tell you something, I would say, think of the the statement, the group email that you’re going to send on the 10 year anniversary of this genocide. Think about what’s going to be in that statement, and put that out right now.”

And of course, that’s never going to happen, right? That’s not a thing. But this idea that, at the end of the day, there’s some other worse outcome, is so compelling that there’s really nothing you can say at one point. It was one of the few times where I lost my cool, because I was having one of these discussions, and after a while, I just said, “Look, stop for a second. Let’s say Biden wasn’t just a centrist. Let’s say he was everything you ever dreamed of as a politician, every policy you’ve ever imagined, everything he is your dream politician. And all he did wrong was just order the execution of your kid, right? That’s just one kid, right?” I found myself going to this incredibly dark place that I don’t really even want to talk about in this podcast. It’s not making me sound like an amazing human being. But we were getting to this place where I knew that it was a foregone conclusion that however, many of those distant brown people were wiped off the face of the earth, it did not matter in the calculus of the discussion we were having. That was just a rounding error, right? That was just being divided out of the equation.

I think, honestly, if you go to that place where you just decide certain groups of human beings aren’t human, then that argument makes perfect sense. Because it hasn’t come to your door. And I struggle against the idea that the only way I’m going to convince you that something horrific is horrific is if I can extrapolate to the day that horrific thing comes to your door. Because in the end, I have abdicated morality as an idea, and I have abdicated our obligation to give a shit about one another as an idea, and I don’t want to do either of those two things, which is why I go back to this notion that, however this discussion ends, I’m no longer interested in changing your mind. That’s a conversation for you to have with yourself.

VVG: So throughout the book, you write about your childhood. You write about various moments of your family being on the verge of departing somewhere, crossing some border, and those transitions being halted for what irrational reason we don’t necessarily know. You talk about your father taping X’s on windows to give you the impression that that will keep something safe.

And you, at various points, juxtapose your own child with say, the 500 tabs you have open showing the carnage happening to Palestinian people, including children. You’ve written so clearly and named so painfully so many things that people have a hard time naming. I’m interested in thinking about the problem of how to name and articulate this to children who are, at present, more aware than they ever have been before, perhaps, of the world’s fragility, of the lies it is telling, which have traditionally been held as a part of the innocence to which they are entitled, or some children are entitled. There’s this not-level playing field which gets at exactly what you’re talking about. Some children are entitled to not know about these things while other children are being blown up. Some children go to a school where there is a mass shooting, and other children are waiting for that to come to their door. How do we talk to children about this? How do you talk to your child about this? And as they’re getting older, as they’re entering this world full of lies that they should know how to see and name for themselves?

OAE: I’ve done a monumentally bad job at this in my own life, again, as a direct result of cowardice. My son’s too young to be aware of any of this. My daughter’s just old enough that she’s starting to become aware, whether I like it or not. You have these kids, and you want to cover them in bubble wrap, and then slowly, you watch that unravel as the rest of the world kind of starts to interact with them. One of the things that I really, really despise as an argumentative or conceptual trope is this notion that kids are resilient. It comes up all of the time. You know, “kids are more resilient than we give them credit for.” I would really like to live in a world where we haven’t got the slightest idea how resilient kids are, where nobody needs to find that out. I found, particularly with my daughter, who’s very, very smart, certainly far smarter than I am, and very sensitive and very sweet, that, of course, my natural instinct is just say nothing, and that makes sense, right? To a certain extent, I’m not going to sit her down and be like “In 1967 the borders were…” We’re not going to do that, right. Nor am I going to try and explain to her how it is that human beings can become desensitized to the kind of things that, largely, many of us have become desensitized to.

But I do find myself trying my best to broach the subject of how to be a human being that, at the very least, considers themselves to be part of a community, considers that there exists an obligation to care for one another. There are various ways I’ve tried to approach that, but a lot of them have to do with this notion that we live in a world where there is a reward punishment equilibrium, and we see that right now. I don’t think the majority of human beings are sitting around cheerleading a genocide. I do think there’s a lot of people who understand the reward punishment equilibrium and have decided that their best interest is in keeping their head down. I get where that’s coming from. But I was at this event in Dublin, and the last question of the night came from this kid who was maybe thirteen-years-old and was talking about this notion of, “How do we behave in the world, knowing that this horror is ongoing?”

I found myself going back to when I described the scene in the book Aaron Bushnell, at the moment where he killed himself, which is a horrific moment. I would never ask your listeners to go look that up or anything like that. But if you are aware of that moment, you know that in the end, after he is self-immolated, that there’s, there’s like a security guard and a cop who show up, and one of these people is asking for a fire extinguisher. And the other guy is pointing his gun at the flames. And I said, “Look, the closest they can come to answering your question is to say that throughout your life, you are going to be put in positions where you can be one of those two people, and there’s going to be endless reward for being the sort of person who’s comfortable with pointing the gun at the flames, and if you choose to be the other human being trying to put out the flames, you are going to have an uphill climb for the rest of your life. Nonetheless, I urge you as strongly as I can to be that person.”

Essentially the way that I’ve been approaching this with my daughter, not in those terms, but in the sense that regardless how much punishment there might be for giving a shit about another human being, and regardless how much reward there is for doing the exact opposite, you have to have some sort of internal compass that allows you to seek to put out the fire, rather than point your gun at the flames. Whether any of that has stuck, I have no idea. Obviously, as your listeners are now aware, I’ve done a very hamfisted job of describing this in any kind of eloquent way, but that’s been the axis along which I’ve approached these subjects, and probably how I’m going to continue to do so as she gets older.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy. Photograph of Omar El Akkad by Kateshia Pendergrass.