As a literary translator who was born in Tokyo, raised in Los Angeles, and now ping-pongs between the two cities, I often find myself describing books (that I neither wrote nor translated) to readers of both English and Japanese. Part of this includes an attempt to offer a cultural snapshot to someone beyond the country or language it was published.

Article continues after advertisement

In Japan, I have reported back to curious readers on the skyrocketing popularity of Asako Yuzuki’s Butter in Polly Barton’s English translation (assuring them that the Japanese media is not exaggerating this time), or about the number of anxious fans awaiting the next Sayaka Murata translation by Ginny Tapley Takemori. To English readers, I find myself detailing the Akutagawa and Naoki Prizes and their impact in Japan’s literary world, sharing which award leans more literary (Akutagawa) and which toward propulsive plots (Naoki). Both birth bestsellers twice a year. I go on about Japanese powerhouse authors from the nineties and early aughts that need to be reintroduced in the way that Fumio Yamamoto finally is (joy!) in Brian Bergstrom’s translation of The Dilemmas of Working Women. All the while, I ask myself, why do I care so much about the story behind the story?

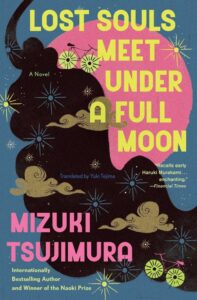

Years before I would find myself in the astonishingly fortunate position of translating Mizuki Tsujimura’s bestselling novel Tsunagu (Go-Between) into English with the title Lost Souls Meet Under a Full Moon, I devoured a 2016 article on Lit Hub titled “10 Japanese Books by Women We’d Love to See in English,” a brilliant list of then-undiscovered novels compiled by translators Allison Markin Powell, Ginny Tapley Takemori, and Lucy North. This was before I became a literary translator, before I knew the trailblazing translators in person, back when I was simply a fan of Japanese novels, many of which I read decades ago as a teenager who raced to the PARCO bookstore in Kichijoji on family trips to Japan.

In my messy, heavily-postered teenage room back home, I had a hidden shelf devoted to paperbacks written in their original language by Banana Yoshimoto, Yoko Ogawa, Hiromi Kawakami, Kaori Ekuni—kept out of sight because no one at school could ever know that I spoke or read Japanese. All day long I switched back-and-forth from my American to Japanese selves, depending on the activity. Mall shopping, belting oldies in the car, going to baseball games, and fighting with my siblings were done by my American self. My Japanese self stepped in when it came time to attend Japanese school, flip through idol magazines, watch Japanese dramas, dream of hatsukoi (first love), eat umeboshi, and talk to my parents. The one thing the two sides had in common was reading—but only one language was read out in the open.

All day long I switched back-and-forth from my American to Japanese selves, depending on the activity.

Looking back now, I wish I’d been lucky enough to grow up reading Mizuki Tsujimura (though she too would have been a child then). Her insight would have helped me understand my discomfort, I think, to know that somewhere in the world, painfully shy teenagers who looked like me were also trying to find their place in a classroom filled with loud, fearless people.

I marvel now that of that reading list published in 2016, nine of the ten authors mentioned have or will soon be translated into English. The translated Japanese novel has come a long way in just under a decade, due in large part to the work and initiatives of translators such as Allison, Ginny, and Lucy.

One title in particular caught my eye as I went down the list: Tsunagu!

I want to live in a world where Tsunagu can be read in English, I thought. I’d read the novel in Japanese when it was first published in 2010 and had been riveted by Tsujimura’s storytelling. Ginny’s plot description in the article is spot-on: After his father killed his mother and committed suicide, Ayumi is brought up by his grandmother, Aiko. When he reaches high school, Aiko begins training him in the secret art of a spirit medium, facilitating one-off reunions between the living and the dead.

While many English readers may be quick to assume that Tsujimura’s novels are meant to heal, the word most often used to describe her work in Japan is sasaru. It means stab, sting, turn a knife in my heart.

While many English readers may be quick to assume that Tsujimura’s novels are meant to heal, the word most often used to describe her work in Japan is sasaru. It means stab, sting, turn a knife in my heart.

Since her debut in 2004, Mizuki Tsujimura has written over forty books in Japanese, three of which have been translated into English, with more on the way. In Japan, eight of her novels have been adapted into full-length feature films and her name comes up regularly in both pop culture and literary contexts. Tsujimura made her start as a mystery writer. She chose the pen name Tsujimura, borrowing the Tsuji kanji character from Yukito Ayatsuji, a master of the genre, whom she became enamored by in elementary school. (In high school she wrote over a hundred fan letters to the author, even receiving a handwritten reply.) She now considers him a mentor.

Last fall in Tokyo, I attended a rare event with the author at the famed Kinokuniya Hall Theater in Shinjuku commemorating her 20th anniversary as a novelist. Three hundred seats, filled in a flash. As the audience hung on her every word, my ears perked up when she shared her experience writing Tsunagu, which I happened to be translating.

She wrote the book early in her career when she had just entered her thirties, too soon to be writing about death, she says. In the novel, a high-schooler named Ayumi is ordered by his grandmother to take over her role as the go-between, setting up meetings between the living and the deceased for one night only. “I don’t plot out my stories before I start writing,” she says. “And I didn’t know where Tsunagu would take me initially. I just thought it might be interesting to explore situations in which a go-between meets with different clients.”

But gradually, she says, her character Ayumi began to struggle with his responsibility as the go-between. His job was to reunite the emotionally burdened with their loved ones, but what right did the living have to call on a dead person for their own comfort?

Tsujimura followed his need to understand. “Ayumi was conflicted by his position of being able to manipulate fate. And it was only by writing through his inner conflict that I understood why I was writing about death so early in my life and career,” she said. “Would the writing be easier if I knew what I wanted to write from the start? Possibly. But then I probably wouldn’t be able to write.”

For fifteen years, the novel has been passed from reader to reader in Japan, but it has become apparent in Tsujimura’s twenty-year career that her words aren’t just contained in the pages of a book, in a single language. Her books speak to the universal, and I’m honored to be able to bring her work to English readers. As a teenager who once ached for stories of young people like me, my oft-stung adult heart fills to think that we can now share Tsujimura’s tales with the people we’ve grown up with, grown up around, and grown apart from. For you, and your younger self, I hope you will read.

_________________________

Mizuki Tsujimura’s Lost Souls Meet Under A Full Moon, translated by Yuki Tejima, is available now from Scribner.