On paper, very little record remains of my paternal family history. There is a two-page Word document from my great aunt summarizing what she remembers being told of her parents’ journeys fleeing the Armenian Genocide, and the manila folder filled with newspaper clippings about the genocide collected over decades by my grandfather. There are a few faded photographs and the stories passed down, becoming more fragmented by generation, some memories lost altogether.

Article continues after advertisement

In her frequently cited essay, “The Case Against the Trauma Plot,” Parul Sehgal argues, “Trauma has become synonymous with backstory, but the tyranny of backstory is itself a relatively recent phenomenon.” I’d argue intergenerational historical trauma often takes this a step further, the horrors of yester-generation becoming the exigence for present action. In other words, the entirety of a story or novel’s inciting incident only exists because of the historical trauma that precedes it.

In American literature, this is perhaps a relatively recent phenomenon too, one that could be attributed to a lack of global (and local) educational foundation. Writers dealing with historical atrocities are forced to handfeed research to readers who might have never learned much if anything about them in school. Too often I’ve been told by readers that they were not aware of the Armenian Genocide in any capacity before reading my work. To me, that says more about the world we live in than my writing, but whether or not I want to admit it, there is an unshakeable responsibility in being that first touchpoint, especially given Turkey’s decades of revisionism and contestation.

I’m not naïve enough to think I made something new, but I take some pride in having found my own way.

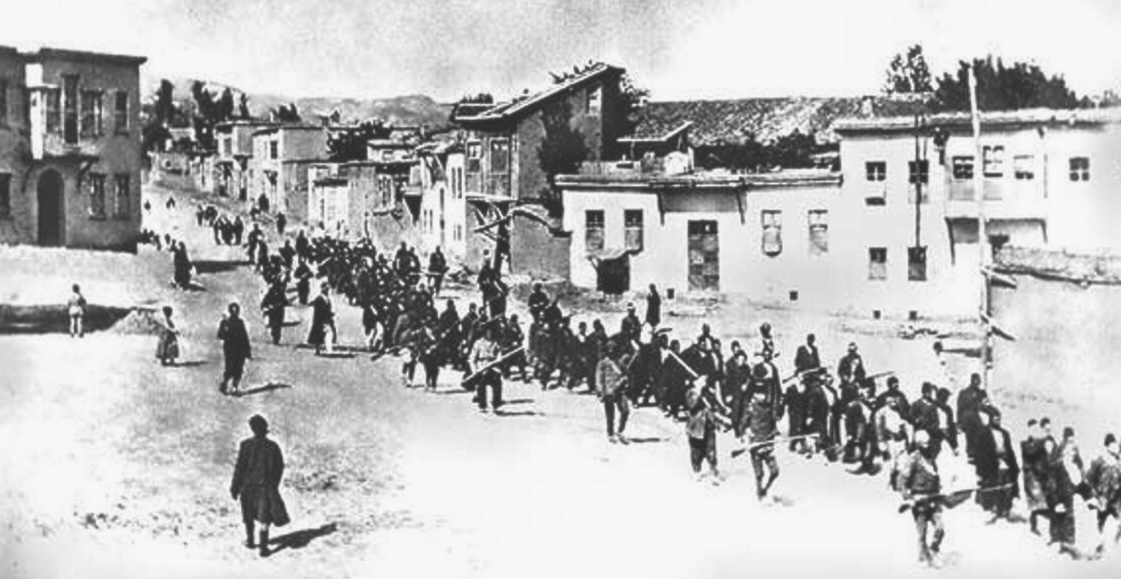

During graduate school, I read stories about the Armenian Genocide that were meticulous in their historically accurate reimagining of violent atrocities: death marches, ethnic cleansing, rape, forced starvation, and displacement. I requested century-old newspaper and magazine clippings from library storage. I scanned current articles about the push for formal acknowledgment and the Kardashian pilgrimage to Armenia. I pulled statistics from reports covering the high rates of journalists being jailed in Turkey and Turkish laws that discouraged speaking out about the past.

As an academic, I read and reread these texts and considered the necessity of putting the historical events of the Armenian Genocide in scene, of showing for a largely uninformed audience horrors that have been and are still being maliciously revised and erased. I understood the didactic logic of forcing the reader to intellectually and emotionally live through those brutal moments, but the personal distance nagged at me. I had learned this particular history in my own adolescence and had recited it many times over the past twenty years. I did not want such images to monopolize my creative output.

In Michigan, where I grew up, curriculum dedicated to the Armenian Genocide, Holocaust, and other mass atrocities was not mandatory until 2016, a decade after I had graduated high school. When I was a junior, during a unit in history class focused on World War I, I remember scouring our textbook and asking the teacher if we would talk about the Armenian Genocide.

At the time, her response surprised me. “Well, I don’t know much about it,” I remember her saying, “perhaps you’d like to inform the class?”

For the next five minutes, I tried my best to fill in my classmates, not realizing that such an impromptu request of a sixteen-year-old was kind of fucked up. But that moment illuminates the central dilemma for anyone trying to write fiction set against a little-known historical background.

When it came time to write my own novel, Waterline, I couldn’t bear to recreate the inherited atrocities from which I felt very far removed. I fretted over historical accuracy and precision, the risks of exploiting familial trauma, and my own discomfort performing gratuitous violence on the page. I decided I wanted to write a novel about Armenian characters living in southeast Michigan today, a family whose legacy was permanently imbued with the genocide but not defined by it. These characters knew bits and pieces of their family lore but had to fill in a lot of gaps for themselves. They dealt with ethnic ambiguity and exotification but were otherwise assimilated.

Sometimes I want fiction to leave me with more questions than answers. There’s still a lot I’m figuring out. There’s a lot I’ll simply never know.

I wrote and revised the novel with a short but rigid set of rules. The most important constraint was that no more than ten percent of the total word count could talk about or take place during the Armenian Genocide. I was determined to write an intergenerational novel that did not spend most of its time and energy in the deep past. In a novel of 80,000 words, even dedicating eight thousand of them to century-old trauma felt like too much, but the firm boundary allowed me to work with more confidence and creative freedom.

Not everyone shared my enthusiasm for this artistic decision. The first agent I queried asked for the full novel within a few hours, but ultimately replied, “the manuscript should be revised to give the reader a stronger sense of the sweeping history.” Over the next two years, I was told dozens of different ways that my very intentional decisions related to content caused major issues with structure, plot, narrative arc, character development, pacing, or, in a couple candid responses, the novel’s ability to sell.

At an earlier point in my career, I don’t know that I would have held firm. I might have reimagined the novel’s structure and narrative arc, prioritizing longer chapters that recounted the death marches, starvation, and forced displacement of Armenians fleeing the Ottoman Empire during World War One. I ask my students all the time, what’s nonnegotiable in your work?, but it’s not always easy to know when you’re reasonably holding onto your artistic vision and when you’re ignoring practical advice for the betterment of the project. I’m not naïve enough to think I made something new, but I take some pride in having found my own way.

Many of my favorite works of literature spend their entirety set in times of historical violence and upheaval. There can and should be books that spend twenty or fifty or ninety-nine percent of their time grappling with the horrific events of the Armenian Genocide or other historical atrocities. Those books are the ones I recommend to friends and hold dear and that guide me.

Yet, as I revised Waterline again and again, part of me preemptively wanted to tell hypothetical readers to do their own homework, not out of any sense of resentment, but instead the hope they would be inspired to learn more after experiencing the fragmented history my characters try to piece together. Our past and our present are inexorably connected, but not always easily filled in. Sometimes I want fiction to leave me with more questions than answers. There’s still a lot I’m figuring out. There’s a lot I’ll simply never know.

__________________________________

Waterline by Aram Mrjoian is available from HarperVia, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.