Moving to Paris made my cheeks hurt. After a decade since I’d last worked in France, I found myself back in the land of one of my ancestors’ other colonizers. My Broca’s area could still conjure the language easily enough. But the fast-twitch fibers in my orbicularis oris had atrophied, making the physical production of French’s extra vowels sounds more labored and slower than I was trying to talk.

Article continues after advertisement

Luckily, under real stakes, my muscle memory kicked in. I acquired a lot of vocabulary about living in a city I’d never needed to know before and my face stopped aching. Now, the real training could resume.

I wasn’t there to avenge my postcolonial trauma but that wasn’t not on the table, either. I hold deep ambivalence towards my proficiency in French, but in the city Foucault called home, how could I not be drawn to the power and potential of language? I was, after all, in the midst of revising a novel.

I began teaching English at a local high school and emailed my novel editor asking to push back my first deadline by a couple months in exchange for a bigger overhaul. I had students ages 10 to 18+ with a wide range of English fluencies in each class and a few hundred pages where I was trying to weave together a wide range of linguistic registers with more deftness.

The teleology of showing off my French wasn’t to be liked but to achieve results.

I hoped to play Cool Teacher as a path towards both rapport and a more effective pedagogy. I made jokes that showed I could make the language work for me and thus, could maybe make it work for them. In those crucial first impressions, the students exchanged glances and blinked at me as if to ask, Did you make that grammatical error on purpose and are we allowed to laugh? To make my joke funny, I had to tell them, Yes, I was messing with their language, and it was okay to laugh. Maybe explaining your jokes can work across a perceived language barrier. At least, at first. Soon enough, my humor translated in real time.

The teleology of showing off my French wasn’t to be liked but to achieve results. I wanted to help my students prepare for their English exams. I wanted to access France’s social state.

With every prong of the government’s convoluted bureaucracy, I hoped fluency could grease the gears. To activate my health insurance, I had to follow up and rephrase until I produced the right code. While some blockages couldn’t be expedited with language, the pressure to assimilate had me behave as if there was some threshold of French that would exempt me from linguistic racism, classism, and colonialism. I bought into it without buying it.

*

Elsewhere I went out to find new friends, people whom I wanted to like me. Unsurprisingly, a good chunk of the people I got on with best were fellow postcolonial subjects with other first languages. Slowly, I acquired rhythms and colloquial registers beyond the standard Parisian accent my early teachers had guided me toward. One day, I found myself speaking to a civil servant with the relaxed consonants and wide vowels I exercised with a new friend and was met with confusion. I quickly repeated my request with prissified diction and all of a sudden, there was a solution. Lesson learned.

On New Year’s Eve, I spent the afternoon working on novel revisions at one of my favorite libraries. I got stuck trying to find a more interesting line for a character to say than the tepid version I had last settled on. I don’t really get writer’s block but that afternoon it found me. Panicked, I got up and stared at the Seine (I know, poor me) til finally, the line came to me. I started tearing up over language. Maybe Foucault was on to something.

That night, I went to a dinner party where French was none of our first language. When it was time to introduce myself, I opened my mouth and choked. I couldn’t conjure a word in French or English. After a couple seconds, I frogged up a Bonsoir and passed the potato. For the rest of the night, I had to think so hard to produce the simplest phrases. I knew this phase was coming, but was still taken aback that just a few hours of revision triggered subtractive bilingualism.

The next day, I biked around town, building my mental map of the city and minimizing conversations so my brain might rest from language a bit. But my deadline extension quickly approached and I had to barrel ahead. I worked the words til my own language no longer made sense to me. I kept going til a delirious logic held stable enough to turn a page. Somehow, I shifted from the so many syntaxes of English humor construction bouncing in my brain to speaking French by default. I crossed an invisible inflection point and my bilingualism was becoming additive again.

When I heard about Centre Pompidou’s three-month strike, the longest in its history, I picked up on a loose thread of narrative. With the 2024 Summer Olympics looming, I heard the chasm between the official rhetoric presenting the Games at a town hall and the way people actually talked about the internationalism pageant (my words). I began conceptualizing a freelance pitch.

Even if writing about Paris helped ease the transition, my mind was still flailing in this last codified stage, reverse language shock.

I conducted more pre-reporting than I normally would because whatever story was taking shape gave context for me to have conversations with people I wouldn’t readily have had access to otherwise. I convinced total strangers that some nobody freelance journalist from America was worth an hour of their time. I calibrated each source’s varying tension between deference towards and resentment of American cultural hegemony. I translated French cultures of protest and labor politics towards American outlets and got lots of passes. A mistranslation or just a mis-fit?

When my pitch was finally picked up, I spoke with more activists and workers both unionized and itinerant. I pored over transcriptions and files trying to piece together a narrative, and then, to find the sound bites of language that best enriched the story I could shape within word count. With my book editor’s encouraging notes, I took a knife to the next draft of my novel to accentuate its slopes with the most finesse I could access. I translated the snappiest quotes into English to tell a story about the slogans of compulsion and resistance encircling the upcoming Games. I left well over 95% of interview hours behind and trimmed thousands of words from my novel. Each small chisel felt like a big axe.

When I returned to the U.S, edits for that article continued into the summer. I’d been working consistently but had somehow fallen behind pace for this next novel deadline. My brain was habituated to the nimbleness I was asking of it. But even if writing about Paris helped ease the transition, my mind was still flailing in this last codified stage, reverse language shock. I woke up and absentmindedly spoke French and all around me, people spoke English. And still, I wrestled with words and rewrote grafs.

My less-than-a-year in Paris was the most linguistically dense of my adult life. It’d be incredibly convenient copywriting if I could proclaim that my facility with words reached new virtuosic heights. Please believe that, if you’d like! But I won’t pretend to know my own game that well. When a friend from Paris was visiting town, I got nervous wondering if I could still make her laugh.

__________________________________

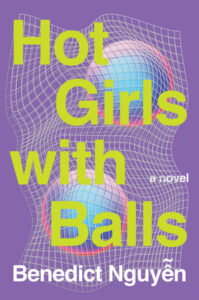

Hot Girls with Balls by Benedict Nguyễn is available from Catapult.