“Art is the language of the soul, the universal bridge that connects us all.”

–Christo

*

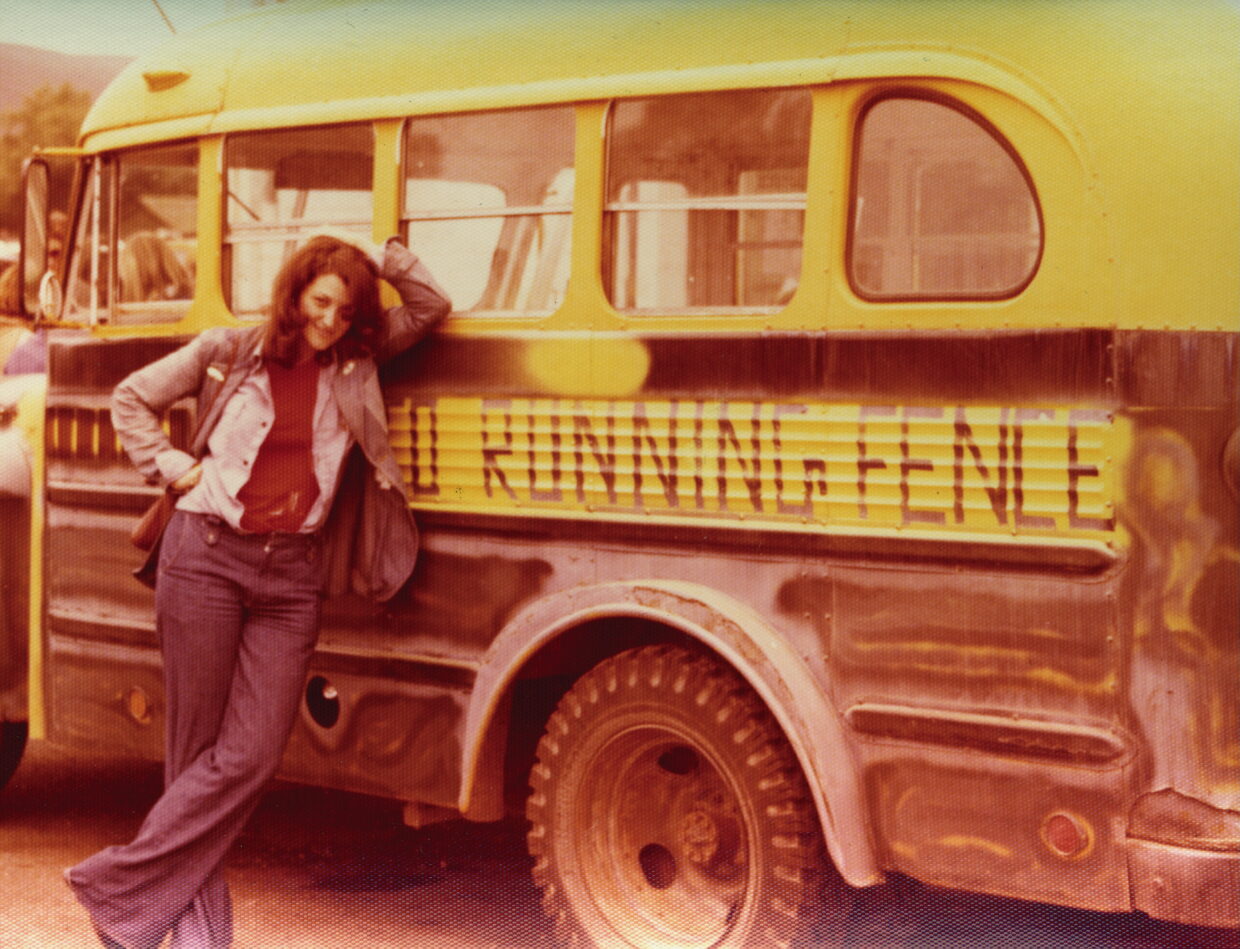

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s passion, humor, and obsession were contagious. The Christos effortlessly burrowed through obstructions, overturned impasses, and fought back legal challenges and, generally, turned perceived difficulties into advantages. That Running Fence might not happen never occurred to them.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude were known for creating large-scale site-specific art installations often made of draped fabric and that involved public as well as private property—requiring permits, permissions, and access.

Running Fence was envisioned as a fabric-laden fence that would traverse Sonoma and Marin counties in Northern California to the sea, crossing roads, highways, and private property. Running Fence was first proposed in 1972 but took four years to fully realize.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude hired Peter Selz to be the director of Running Fence. Because of delays, Peter, having committed to spending a year in Israel, turned to me to manage all aspects of this sprawling project.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude became ever more insistent that the vision of Running Fence would not be complete unless it disappeared into the water.

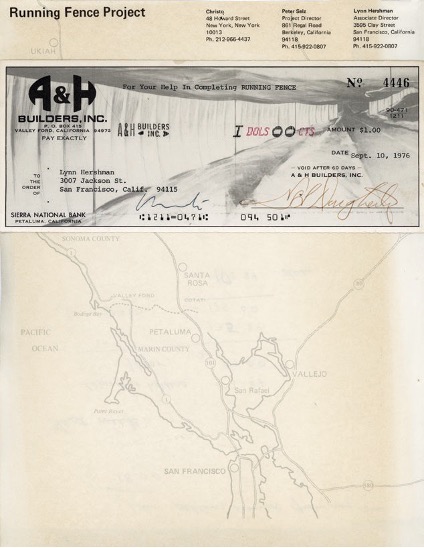

Being Running Fence’s associate project director was my first formal job in the arts. Christo and Jeanne-Claude were successful, acknowledged, and respected conceptual artists. I wanted to learn as much as I could from the Christos. My salary for the four years it would take to complete this artwork would be one dollar, plus a collage by Christo.

For Running Fence, I was expected to travel regularly to Petaluma (about three hours north of San Francisco), where Fence would be constructed. Work began predawn, at 3:30 AM. We met with farmers before cattle-milking, hoping to entice them to permit access to their property for the two-week duration of Fence. In a relatively short time, we convinced fifty-nine landowners to participate. There were seventeen public hearings, and the creation of an environmental impact report. Three legal firms were engaged to oversee the planting of 2,050 poles, each 62 feet apart, embedded 3 feet into the ground that, together, would suspend 165,000 yards of fire-resistant nylon fabric over and across the undulating landscape. The final shape of Fence was to be determined by whatever land-use permissions were granted to the Christos. I was commuting to Petaluma and took Dawn with me. She would sit in the back seat doing her homework.

Even with an environmental impact report citing the safety of Fence, Christo and his team never secured the final permission necessary to allow it to enter the Pacific Ocean. After each denial of permission, Christo and Jeanne-Claude became ever more insistent that the vision of Running Fence would not be complete unless it disappeared into the water.

The final days of the project were fraught with a relentless quest to remain on schedule. During the final week, the crew worked nonstop for sixty hours in a heat wave that parched energy and drained our bodies. Supplies of salt, food, and water were meager. Some workers collapsed from sunstroke.

Continuous five-hour round-trip treks to the San Francisco International Airport to greet arriving art curators and critics ensued. Longtime friends of the Christos who came to see their latest work unfurl included the critic Pierre Restany from Paris, the curator Germano Celant from Italy, the museum director Pontus Hulten from the Netherlands, and the curator Mr. X from Switzerland. Thankfully, Mr. X did not remember our prior meeting at Peter Selz’s dinner. I drove each of them through the twenty-four winding miles of Running Fence.

As the project neared completion and after several years of absence, Peter Selz returned to reclaim his title of project director. In this final phase, with international guests present, lavish dinners were orchestrated nightly, which was itself a feat, considering there were few good restaurants in Petaluma at the time.

Amid the frenzy, I received a call from the California attorney general’s office. They had been alerted that Running Fence was planning to enter the ocean despite having no permit. The attorney general was adamant that if Running Fence broke the law, workers would be arrested and jailed, and contractors would lose their licenses. I assured him that Running Fence’s configuration and eventual path would conform to whatever was legally allowed.

After Christo learned that he was again denied permission to bring Fence into the Pacific, he whispered in my ear, “I’m going to do it anyway.”

“But workers might lose their license, or be put in jail,” I responded, concerned.

He smirked, indicating that it would never happen.

Jeanne-Claude’s parents, a French general and countess, arrived in Petaluma the day before the scheduled completion. Jeanne-Claude drove them through the winding landscape while work continued at its furious pace. Christo, meanwhile, hid in the bushes to avoid being spotted by helicopters sent by the attorney general’s office to monitor the situation. Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s attorneys threatened to quit if they defied the law.

It was my belief that we needed to let the contractors and workers know their potential risks and allow them to make decisions on whether to participate. Their livelihoods were at risk. Jeanne-Claude, furious that I suggested letting workers have a choice in this, banned me from all following dinners and celebrations. I suspected she also initiated a rumor that I had suffered a psychic break.

Among Christo’s visitors, Pierre Restany became a close friend. Pierre was short, with a white beard and flamboyant wild hair. He looked like an elf and was the only one who appreciated my dilemma. His intelligence and compassion helped enormously and launched our lifelong friendship.

On the very last day, the New Yorker writer Calvin Tomkins and I took a helicopter ride over the landscape. From above, we saw Running Fence in its expansive brilliance, gloriously defining the landscape and disappearing as its path led to the sea. I completed my work in the office while Jeanne-Claude managed the project in a secret location a mile away (her stepfather, a general, must have inspired the need for a hidden office). If Running Fence was a war, Jeanne-Claude was clearly the commander.

On the morning of the scheduled opening of Running Fence, an odd mixture of farmers, ecologists, engineers, international art patrons, critics, curators, and press gathered on the cliffs of Bodega Bay, overlooking the hills of Sonoma. Together, we watched the violet sunrise light the landscape. Breathless, we waited for the completion of Running Fence.

Spirited, political, and deeply kind individuals, the Christos were passionately devoted to their artistic vision.

Christo emerged at the water’s edge with a bullhorn.

“PULL,” Christo shouted.

The crew obeyed. The cords gave way, unfurling in one dazzling thrust the release of the entire Fence. White fire-resistant fabric floated towards the water, then disappeared into the deep ultramarine expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude disregarded all threats of legal action, directing Running Fence to complete its predestined voyage into the sea. Christo’s assumptions were correct. They paid only a small fine to the county. No one was arrested or put in jail; no workers lost their license.

My contributions to Running Fence went mostly unrecorded. Calvin Tomkins’s Running Fence account in The New Yorker made no mention of me (for which Tomkins later apologized). The local artist Tom Marioni wrote his own account in which he omitted me because, as he later told me, “Nobody had heard of you.” I appeared in the Maysles Brothers’ Running Fence film for less than three seconds. Nonetheless, in working on Running Fence, I acquired vital organizational skills and was introduced to many future collaborators, such as Annina Nosei (Weber) who opened a gallery in New York in 1980. I would later exhibit in her gallery with other unknown artists, such as Julian Schnabel, Francesco Clemente, and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Spirited, political, and deeply kind individuals, the Christos were passionately devoted to their artistic vision. In his essay “Civil Disobedience,” Henry David Thoreau reminds us that “willingly breaking a law that is unjust and paying the penalty arouses the conscience of a community.” Christo and Jeanne-Claude had a profound understanding of this. The Christos honored their promise by gifting me with a wonderful collage in addition to my one-dollar paycheck. Thirty-eight years later, I donated the collage to MoMA, which until then owned no work by Christo.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Private I: A Memoir by Lynn Hershman Leeson. Copyright © 2025. To be published by ZE Books on Nov 4, 2025. Used with permission.