Keisha N. Blain Considers the Pioneering Black Women Who Fought For Human Rights On a Global Stage

If the United Nations represented an expansion of human rights discourse in the global world order, then its establishment served to bolster Black Americans’ resolve to agitate for rights and freedom on behalf of all colonized and oppressed peoples, including those in the United States. Black women were often at the forefront of these efforts.

Article continues after advertisement

While some Black women championed human rights at the grassroots level, others worked to advance human rights in more formal roles at the United Nations. Because of their status in a predominantly white and male-dominated organization, Black women working for the UN were often “outsiders within,” who had to find ways to assert their voices and leave a mark, recognizing that their presence alone represented a challenge to the social order. Although they did not hold key leadership positions during those years, Black women found a structured and intellectual space from which to work toward the expansion of rights and opportunities for all people, including millions of Black people living under colonial rule.

Journalist Paulette Nardal was the first Black woman to formally join the UN as an area expert. Born to an upper-class Martinique family in 1896, she was one of seven daughters of Paul and Louise Achille Nardal. Her father worked at the department of public works, and her mother was a schoolteacher and musician. During the 1920s, Nardal joined a wave of Black intellectuals who relocated to Paris to pursue educational opportunities. She attended the Sorbonne, where she studied English. While in Paris, she became involved with the struggle for human rights, openly challenging fascism and colonialism as well as racism and sexism. A devout Catholic, Nardal drew connections between her political work and her commitment to upholding Christian principles. Like Emma Clarissa Clement, Nardal advocated the “brotherhood of man and equality and justice for all races.”

Because of their status in a predominantly white and male-dominated organization, Black women working for the UN were often “outsiders within.”

Amidst the global economic depression of the early 1930s, Nardal co-founded La Revue du monde noir (“The Review of the Black World”) with her sister Jane, Haitian dentist Léo Sajous, and Guadeloupean attorney Henri Jean-Louis. The magazine editors vowed to “defend more effectively their collective interests and to glorify their race.” Their motto—“For peace, work, and justice. By liberty, equality, and fraternity.”—captures their commitment to advancing the global Black freedom struggle.

The magazine’s first six issues featured articles on France as well as other parts of the African diaspora—including the United States, Haiti, the United Kingdom, Ethiopia, and Liberia. In a 1932 article, “The Awakening of Race Consciousness Among Black Students,” Nardal discussed the importance of women’s voices in Négritude, the literary movement led by Black francophone intellectuals that emphasized African heritage and Pan-African culture. Along with the 1928 essay by her sister Jane Nardal on “Black Internationalism,” Paulette’s essay on race consciousness was one of the most iconic and influential of the period. The essay, much like her other writings, “heralded race pride, reclaimed Africa, [and] celebrated pan-Black cultural expressivity.”

One of the hallmarks of La Revue du monde noir was its focus on global liberation for all people, regardless of race, nationality, gender, or class. As European nations—including France—maintained colonial rule, exploiting millions of people of color across the globe, Nardal wielded her writings as a weapon to challenge the global color line. The journal maintained a firm stance against colonialism and “adopted a broad pan-African vision, stressing similarities and commonalities of purpose across the colonized world.” When Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935, Nardal joined a growing transatlantic network of Black women, including Melva L. Price and Salaria Kea, to rally in support of Ethiopians. Similar to Black nationalist intellectual Amy Ashwood Garvey, who launched an organization to support Ethiopia during this period, Nardal co-founded the Comité d’action éthiopienne (Ethiopian Action Committee) with a group of Communist-affiliated African and Antillean men to rally support for the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie against the Italian invasion.

Despite its limitations, Nardal viewed the UN as “the new hope that dawns over the world.”

When the Second World War erupted, Nardal left France to return to her native Martinique. While en route to England, Nardal’s ship was attacked by a German warship. The incident left her physically disabled, requiring her to walk with a cane for the rest of her life. The experience also bolstered Nardal’s resolve to fight fascism and demand expanded rights and opportunities for all. To make a living, she served as a choral director and teacher for several years. In 1945, she established La Femme dans la Cité (“Woman in the City”), a monthly journal that centered the ideas and concerns of Black women in the French-speaking Caribbean. Feminism and internationalism were some of its core themes. Nardal emphasized the significance of Black women’s political leadership and called on Black women to join the global struggle for Black liberation: “[S]ince we have been called upon to participate in the life of the City, let our first contribution to the common good be to imprint on the collective effort toward social justice the mark of peace.” Nardal’s articles also grappled with other pressing issues of the day, including violence and poverty. She implored women readers to join forces together to combat poverty: “No woman worthy of the name woman should remain indifferent to it.” While publishing La Femme dans la Cité, Nardal founded the group Le Rassemblement féminin Martiniquais (Martinican Women’s Assembly). In this role, she worked closely with several global women’s organizations to advance women’s political participation in France.

In November 1946, Nardal left Martinique for New York City to begin her tenure as an area expert for the United Nations. Her friend, attorney Ralph Bunche, brought her in to work for the UN’s Department for Non-Autonomous Territories as well as the Commission on the Status of Women. During the winter of 1947, the Martinican intellectual played an active role in these meetings and advocated for women’s rights and the end of colonialism. By her own account, she worked to “impart information about her country [Martinique] on questions of economic and social significance on non-self-governing territories.” Much of her analysis centered on Black women—especially those residing in the French-speaking Caribbean. Her position as a UN delegate provided a new outlet for Nardal to build and strengthen international alliances. She worked alongside a diverse and high-powered group of women leaders from around the world, including Eleanor Roosevelt, Chinese educator Way-Sung New, and Indian activist Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit.

Despite its limitations, Nardal viewed the UN as “the new hope that dawns over the world.” From 1945 to 1951, she provided regular updates on key developments at the UN in La Femme dans la Cité. In one of her earliest articles, she emphasized its possibilities: “One unique will and one unique hope drive these nations who have discovered the interdependence of human society and who now work toward the liberation of all Mankind.”

__________________________________

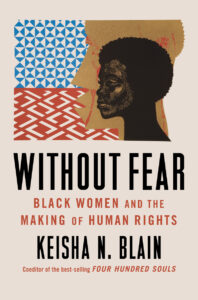

Excerpted from Without Fear: Black Women and the Making of Human Rights by Keisha N. Blain. Copyright © 2025 by Keisha N. Blain. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.