My debut novel, Absence, came out of failure. Many months of failure.

Article continues after advertisement

For nearly a year before I began work on it, I was working on another novel. It was to be longer, more expansive, more determined. I had plans for it. Endless sheets of paper that in scrawls and scratches of ink and pencil detailed roadmaps, in-roads, character arcs, sub-plots and various other diversions.

When I would sit down at my partner’s table in South London with several notebooks spread around me, showing me exactly the way to go. Outwardly, there appeared to be nothing stopping me from completing the novel, nothing I hadn’t already thought of, and so there was no reason for me not to finish it. And yet, despite this–I couldn’t.

At close to two-hundred pages in, I lost interest. No, in fact, I had no reason to complete it. It was, in my mind, in all the sheets of paper scattered around me, already complete. I had finished it in my planning of it.

And by finished it, I mean that all the lights in the house were already on. There were no discoveries to be made, no room for anything to strike me, no shadows for instinct to guide me through. Instead, I could see everything, each character, each pathway, each arc all too clearly.

I could see everything, each character, each pathway, each arc all too clearly.

This is the folly of planning. In my limited teaching experience, I have seen the ways many students try to plan too much ahead. I see this is as them trying to exert a control over the work they are creating, a control which when left unrestrained, more often than not, leads them to overexpose their work.

They, as I was, were trying to give shape, give form to something that cannot yet have form or shape. Those things come in the act of writing itself.

And almost always, the students who would do this would stop what they were creating and begin something new. Why? I would ask. I lost interest. They would reply.

But what is it exactly that is lost in knowing too much? I found in myself a loss of desire to complete the work, a sudden disinterest in it. When speaking once to a friend of mine about this experience, she said it was because I had lost the tension with it. It made me realize something that I had sensed in myself but hadn’t found the adequate language to describe–writing requires tension, and often that tension is one that is formed in space between knowing and not.

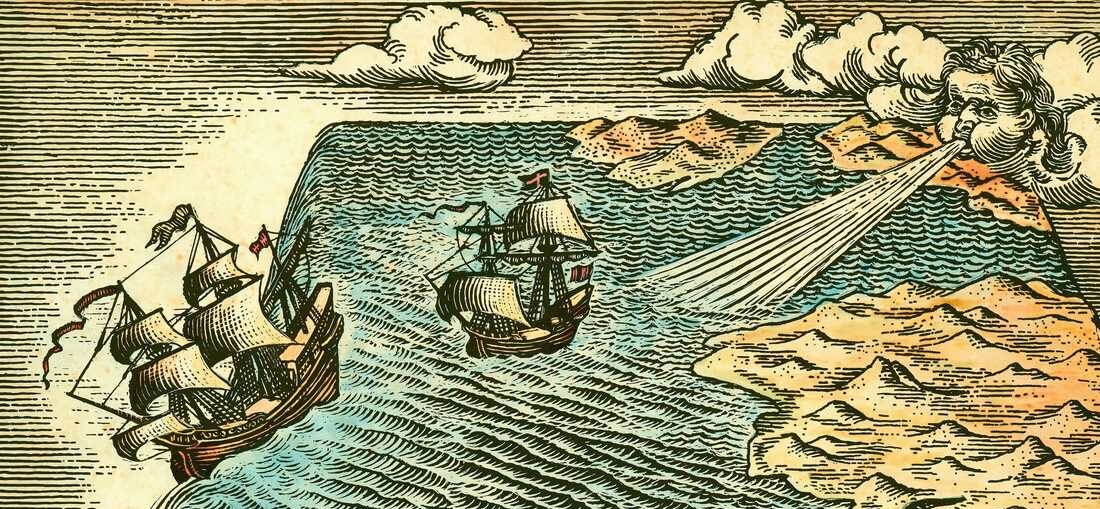

Long ago, I read a famous writer explain how writing ought to be like stumbling around an endarkened, great hall filled with curious artifacts, furniture, décor and paintings with no more than flickering candle leading your way. The more you write into something, the further you proceed through this hall, discovering objects, pulling them out and holding them to the light to see them more clearly, but still somewhat vaguely.

What the writer quite rightly included was, of course, the candlelight. There has to be some balance between knowing and not: you cannot begin entirely in the dark, there must be some notion, some vague direction, however lambent it may be of what course you might take, even despite how far away you might resultantly stray from it.

And of course, the straying away, the emergence of something new, the discovery of the not-thought-of-yet, the unknown must happen in the moment, in the very instant of writing itself. As Knausgaard writes in his book on Edvard Munch, So Much Longing In So Little Space, “writing… must always remain open to the unpredictable and the accidental… [It] cannot merely reconstruct a moment, it must itself be a moment, only then it is in touch with the world, not as depiction but as action.”

The moment, the instant that Knausgaard writes about, “the distance between thought and emotion and language” is where the tension I earlier wrote about exists. The smaller the distance, the greater the tension. When we provide too much forethought, when we plan too much, know too much prior to the act of writing, we widen that gap and disperse that tension.

I ought to say here that much of what I am referring to here largely refers to early drafts. Much of the planning, the knowing, the clarity I am talking about looking to restrain in these initial stages will be infused later into the work, retroactively, in the revision process. The initial drafts of a novel are often where our subconscious patterns emerge of their own accord, those that the text’s logic then follows.

When I began Absence, I did know some things, vaguely, that survived the writing and revision process: I knew the narrator would be nameless, I knew this would be a novel about other people’s stories, I knew there would be a spectral quality to the narrator.

It made me realize something that I had sensed in myself but hadn’t found the adequate language to describe–writing requires tension, and often that tension is one that is formed in space between knowing and not.

There were also things that I knew that didn’t survive: each chapter would revolve around an object, it would be a novel about the way in which we construct ourselves with words, it would have nine chapters. The act of writing is like straining something with the tap flowing above it: things disappear, others appear. But we mustn’t begin with our plate full, we must allow for accident, for fortuity and for disaster.

To paraphrase what William Faulkner once said about literature: writing has the same impact as a match lit in a field. The match illuminates little, but enables us to see how much darkness surrounds it.

______________________________

Absence by Issa Quincy is available via Two Dollar Radio Press.