What does it mean, say the words, that the earth is beautiful? And what shall I do about it? What is the gift that I should bring to the world? What is the life that I should live?

Article continues after advertisement

These are the questions Mary Oliver asks in her essay “Flow,” and they feel, as many of her poems and essays do, close to what I was taught about my relationship, as a Mojave and Akimel O’otham woman, to my Mojave desert and Colorado River. We consider each an autonomous living body, having been created by gods or powerful beings and events, as well as themselves existing as creators of the human and nonhuman bodies which become our experience of living.

I have always believed that the similarities in which our bodies occur—how the great lime and emerald palm fronds in Hawaii, like my own lungs, rise and fall in a music of wind and exhalation, or how the mesquite trees on my reservation at Fort Mojave taught my people to tap root along the shore of our river or in the sloughs, slaking themselves where water is abundant—are not accidental but are an important relationship of the imagination as well as survival.

It isn’t so crazy to believe that this knowledgeable world imagined us itself, from its own values of life. We young human beings learn from this ancestor how to bloom into our existence, in constellation with and alongside the nonhuman beings of the world. Of consequence to one another.

In Mojave, or Makav, our words for body and land are bound together—land is ‘amat, and body is ‘iimat. We care for one as we care for the other, which unfolds a complex and rigorously generous relationship between the I of the human body and the bodies of other nonhuman, living beings; and the collective We who the I becomes through intentional practices and rituals of sensuality. The We is not only what makes the world but who we each are, as autonomous and individual, in the world, alongside one another. Each relies on the presence and devotion of the other. I am of consequence to You, We are of consequence to all life.

Hers is a purposeful language, one that looks not just with attention but with sensual intention, and though awestruck, seeks to hold, even briefly, the unknowns of the energies that make any life.

Oliver says as much and more eloquently in her description of the protective yet fragile shell or home of the ice-cream-worm. She says of this “fortification”: it is “the sand and of it, yet separate from it.” Of being the word that becomes the portal through which she invites us into intimate relationship with what is not often thought of as our body and instead is considered a boundary of our body; the gift of being in the world while also being inseparable from the world.

She offers to us that there is living, and all the structures and tasks that make a human life successful, and there is also the wildness of life, within us and outside of us, in constant constellation and blur, at once patterned and also mysterious—these poems and prose pieces gift us the world as an accumulation of our experiences—what we know—and also propel us toward another depth of our human experience; those things which we do not yet know about the world, and consequently, about ourselves.

It is not only a matter of observation or description. Oliver writes, And that is just the point: how the world, moist and bountiful, calls to each of us to make a new and serious response. Hers is a purposeful language, one that looks not just with attention but with sensual intention, and though awestruck, seeks to hold, even briefly, the unknowns of the energies that make any life. Little alleluias, she called her writings. Not meant to define but to praise, to rejoice in the maker and what has been made, to dare be heard as a whisper or a shout in this immense world. Oliver’s call to make a new and serious response resounds with the June Jordan’s belief that, Poetry means taking control of the / language of your life. In Oliver’s poems, seeing is also feeling and both become an overwhelm for which language is a slight anodyne or ease.

Alongside framing a poetics of wonder and wander, the writings across this trinity of works give us glimpses into how the world taught Oliver to love, a generosity revealed in what has sometimes been seen as lack. I’m speaking now about her practices of solitude and even loneliness. Rather than resulting in a distant or detached existence, her lifelong solitary practices, which were also her practices of witnessing the natural world and creating poetry, became the practices that connected her to a community of readers and writers and through which she herself was witnessed, by them, as someone who loved and was loved. She tells us of the childhood “houses” she built to be alone in, made of a cowl, or a dream, or a palace of grass, and describes them as a symptom of not being social.

Yet in these early structures was where her sensual imagination was shaped, where, perhaps, she became the blue comma herself—as when she writes, off to my woods, my ponds, my sun-filled harbor, no more than a blue comma on the map of the world but, to me, the emblem of everything.

These writings too become the small but powerful shifts in time and pace that we need to truly recognize and then appreciate what it means to be alive, to be struck by the life coursing through us the way it courses within our earth—in rivers and light through the leaves, as jellyfish carried or thrashed by a current, through waves of grass and seas murmuring or crashing our ears, even the sting of salt and dune sand and the rush of sun or stars in our eyes.

This world in which we are of consequence, shaped as violently and tenderly as we also shape it. Marked by and marking.

Perhaps those small houses she built were less like protective shields or limits and more like the portals through which she began to hear and construct the devotional language which became the poetics of how we might love our mysterious, wild, and unknown world enough to protect it.

I’ll leave you with a moment of love that might have been learned in those small houses as well as they were learned on the oceans, dunes, and shores. Oliver is speaking of her lover, Molly. She is upstairs, and Molly is downstairs, and for the first time in her life, she hears Molly whistle. It is so unexpected that Oliver hollers down to be sure it is Molly whistling and not a visitor in the house. Molly’s reply is that, yes, it is she who is whistling, a thing she had done a long time ago and has in that moment learned that she continues to do well.

At this point in the poem, Oliver writes of her beloved, I know her so well, I think. I thought. Elbow and ankle. Mood and desire. Anguish and frolic. Anger too. And the devotions. And for all that, do we even begin to know each other? Who is this I’ve been living with for thirty years? Or for an entire life, we might say. What can any of us make of our momentary intimate lives in such an immense world, with equally immense unknowns, mysteries as great as death or the whale, as deep as love or the ocean, as sad and beautiful as a jellyfish torn and glistening in a small fortress of shore rock?

This world in which we are of consequence, shaped as violently and tenderly as we also shape it. Marked by and marking. Though we might not always, or ever, know what it means, we can’t deny: the earth, the earth is beautiful. How lucky to be in it.

__________________________________

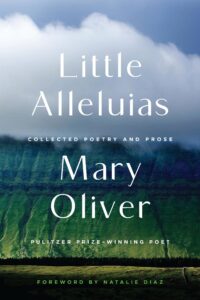

Adapted from Little Alleluias: Collected Poetry and Prose by Mary Oliver, Foreword by Natalie Diaz, published on September 9, 2025. Copyright © 2025 by Natalie Diaz. Used by arrangement with Grand Central Publishing, a division of Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.