The passage came from an obscure and unremarkable book published in Paris. Les Secrets de la Beauté et du Corps De L’Homme et de la Femme [“Secrets of face and body beauty for men and women”] (1855) offered, as its title laid plain, over a hundred beauty secrets—from the secret to perfectly clean hands to the secret for soothing cracked nipples after breastfeeding.

Article continues after advertisement

But there was one passage in particular, on the first page of chapter 9, “Des Cheveux” [“The hair”], that catapulted beyond the pages of this book. Plucked out of the text, translated into English, and sent across the Atlantic Ocean, it landed in American print media in the late 1860s; over the next forty years, this passage was republished—with slight tweaks, variations, and addendums—in more than fifty American newspapers and magazines.

It appeared in newspapers from twenty-one states representing every region of the country, and in national magazines as varied in genre and audience as Harper’s Weekly and The Monthly Journal of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers.

In each of these periodicals, the passage—unmoored from its original context among other beauty secrets—offered a lengthy and extremely specific taxonomy of the connection between hair and character:

Coarse, black hair and dark skin signify great power of character, with a tendency to sensuality. Fine black hair and dark skin indicate strength of character along with purity and goodness. Stiff, straight, black hair and beard, indicate a coarse, strong, rigid, straightforward character. Fine, dark-brown hair signifies the combination of exquisite sensibilities with great strength of character. Flat, clinging straight hair a melancholy but extremely constant character. Harsh, upright hair is the sign of a reticent and sour spirit; a stubborn and harsh character.

Coarse red hair and whiskers indicates powerful animal passions, together with a corresponding strength of character. Auburn hair with florid countenance denotes the highest order of sentiment and intensity of feeling, purity of character, with the highest capacity for enjoyment of suffering. Straight, even, smooth, and glossy hair denotes strength, harmony, and evenness of character, hearty affections, a clear head, and superior talents.

Fine, silky, supple hair is the mark of a delicate and sensitive temperament, and it speaks in favor of the mind and character of the owner. Crisp, curly hair indicates a hasty, somewhat impetuous and rash character. White hair denotes a lymphatic and indolent constitution.

Most of the American reprints ended with the same declaration: “The very way in which the hair flows is strongly indicative of the ruling passions and inclinations, and perhaps a clever person could give a shrewd guess at the manner of a man’s or woman’s disposition by only seeing the backs of their heads.”

In each of these periodicals, the passage—unmoored from its original context among other beauty secrets—offered a lengthy and extremely specific taxonomy of the connection between hair and character.

Both this detailed taxonomy and its emphatic nation-wide circulation reflect a cultural narrative that began to emerge in the United States during the eighteenth century and became dominant during the nineteenth century: that hair had the power to reveal the truth about the person from whose body it grew. People from different regions, racial and ethnic groups, and class backgrounds shared an extraordinary faith in the revelatory and diagnostic power of hair.

Hair was popularly understood to be capable of quickly and reliably conveying important information about a stranger’s core identity—especially their gender (man or woman, masculine or feminine) or their race (African-, European-, or East Asian-descended, or indigenous to North America). Hair could illuminate intimate characteristics of their personality, such as whether they were courageous, ambitious, duplicitous, predatory, or criminally inclined.

In some contexts, hair was even considered more reliable than other body parts at communicating meaningful information about the body from which it grew—more so even than those body parts that usually dominate the study of the body and identity in modern American history, such as facial profile, skull shape, and skin color. As an influential white supremacist wrote in 1853, there was “nothing that reveals the specific difference of race so unmistakably as the natural covering of the head”—the hair.

To categorize hair alongside body parts like skulls and skin is intentional: hair was, indeed, conceptualized as a body part in the nineteenth century. Writers often used the word appendage to refer to hair, such as the Philadelphia hairstylist who described hair in 1841 as “the peculiar or necessary appendage of the human frame.” Moreover, even though barbers and surgeons had long separated into distinct professions, a haircut might be deemed an operation, and frequent haircuts could mean having “hair that is constantly kept bleeding under the scissors of the barber.”

Twentieth- and twenty-first-century scholars have largely overlooked this important nineteenth-century cultural belief because it is so different from our own. For the last century, hair has not generally been viewed as a body part: for most Americans, hair occupies a different mental category from legs or ears or even skin—parts whose skeletal or cartilage construction, whose connections to nerves and muscles, make them integral to the composition of a human body; hair, meanwhile, grows from the body, but is not part of the body.

In the nineteenth century, by contrast, hair was as essential to the body as any of its flesh-and-bone parts. Hair also continued to have significance and power even when it was detached from the body—preserved, perhaps, in a book or locket—because the strands of hair themselves functioned as a synecdoche for their owner.

By taking these assumptions and beliefs about hair’s relationship to the body seriously, this book reveals how nineteenth-century Americans came to understand their hair as a body part capable of indexing each person’s race, gender, and national belonging.

The cultural function of hair in the nineteenth century was, at its core, a reflection of the profound economic, political, and social transformation the United States experienced during that century, when nearly every structural facet of the country changed. An agrarian economy became overwhelmingly capitalist. New forms of transportation and expanding transportation networks made the nation increasingly (though unevenly) connected, linking producers in the interior to national and international markets.

Emergent forms of mass media—newspaper, magazines, national advertising campaigns, mail-order catalogs, even touring circuses and western shows—also made the nation more culturally connected. Industrialization changed how, when, and where people worked, moving hundreds of thousands of people from rural communities into the nation’s growing cities.

Colonization of the western half of North America enlarged not only the geographic size of the United States, but also its demographic composition. Although the Civil War ended with the abolition of slavery in 1865, white Americans continued to politically disenfranchise and violently attack Black Americans into the twentieth century.

Indigenous tribes, too, were the targets of white supremacist violence, as well as forcible institutional assimilation, particularly for Indigenous children. Immigration from Europe and Asia increased rapidly, only to be legally restricted according to race.

Voting rights were extended first to all adult white men by the 1850s, then—thanks to abolitionist and feminist activists—to Black men in 1870, and, by 1920, to women; violence and coercion, however, limited Black men and women’s ability to exercise their political rights until the Civil Rights Movement. Finally, new ways of understanding the world became increasingly prestigious—particularly science, which offered authoritative accounts for bodily and national difference, especially differences of gender and race.

Collectively, these changes affected virtually every major institution that shaped Americans’ daily lives—especially institutions that had offered, for generations, ways of understanding and navigating observable differences between human societies, cultures, and bodies. Crucially, they also put Americans in contact with people they did not know far more frequently than had been the case in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

For the first time in English colonial or U.S. history, interactions with strangers became a part of everyday life for hundreds of thousands of people: strangers riding on street cars, strangers sitting next to them in a theater or lecture hall, strangers buying goods from their shops, strangers trying to sell them a cure-all remedy, strangers coming through town on the train, strangers who did not look the same or work the same way or speak the same language. For many Americans, daily life in the nineteenth century felt like living in a world of strangers.

While the anonymity of this world offered some Americans exciting new possibilities for mobility and even reinvention, others instead felt extremely, even existentially, concerned. Some Americans worried that all these changes—and all these strangers—undermined their ability to discern people’s authentic identities.

This was especially true of upper- and middle-class white men and women, particularly in the North—the Americans likeliest to live in cities, work and consume through the market economy, attend large cultural and commercial events, and thus have significant social and financial stakes in being deceived.

The potential for encountering someone with a falsified identity felt ever greater in this mobile and modernizing world, and deception seemed to lurk around every corner—from the confidence men who haunted American cities, to patent medicines laced with arsenic or lead, to counterfeit currency issued by nonexistent banks, to the deceptive exhibits (often deemed humbug) peddled by showmen like P. T. Barnum.

Furthermore, long-standing methods of verifying the identities of unknown people—such as the cultural norm in most communities that anyone who lodged a visitor in their home or business would inform local authorities—were largely incompatible with these changes, as people became more mobile, and the primary unit of community shifted from small towns to larger cities.

As a result, many nineteenth-century Americans became interested in creating new methods for evaluating unfamiliar people quickly and reliably. The cultural authorities of the emergent middle class devised what historian Karen Halttunen has called a “cult of sincerity” in the 1830s—a response to the vexing challenge, faced by “the aspiring middle classes[,] to secure success among strangers without stooping to the confidence man’s arts of manipulating appearance and conduct.”

Conveying oneself as sincere became fundamental to identifying oneself as part of the middle class— until, in the 1850s, the performance of sincerity became, itself, insincere. Others tried solutions tailored more specifically to the fluidity of the market economy.

For example, Lewis Tappan’s Mercantile Agency—a prototype for the modern credit-rating agency—opened in New York in 1841, offering businessmen detailed financial and personal information to help them evaluate the creditworthiness of potential business partners (and thus avoid getting scammed). Even commercial amusements that played with illusion, such as trompe l’oeil paintings and chess-playing automatons, helped train Americans of all classes to identify the signs of deception.

Instead of emphasizing a process of agency, self-discovery, and self-acceptance, the nineteenth-century search for embodied truth instead focused on innate, even biological truths visible in the human body itself

Yet no methodology or category of evidence was as compelling to nineteenth-century Americans than the human body itself. In scientific tracts, medical journal articles, advice guidebooks, conduct manuals, and the pages of popular newspapers and magazines, nineteenth-century scientific and cultural authorities attempted to identify, measure, and classify parts of the body that were impossible to fake.

Even the best confidence man’s performance, they argued, could not obscure the truth that was evident in his physical form. In a nineteenth-century context, truth—a person’s true identity—was understood quite differently than its twenty-first-century usage. Instead of emphasizing a process of agency, self-discovery, and self-acceptance, the nineteenth-century search for embodied truth instead focused on innate, even biological truths visible in the human body itself.

As historian Stephanie M. H. Camp put it, “By the nineteenth century, most Americans believed that they could know a great deal about a person simply by looking.” The body could reveal information about who a person really was—information about their inherent personality, behavior, race, and gender—regardless of how that person wished to be perceived. The body, in other words, was a tell.

The most well-known sciences that emerged from this search for authentic meaning in bodies were physiognomy and phrenology, which claimed that a careful examination of a person’s facial features or head shape, respectively, would reveal qualities of their character with scientific precision.

Physiognomy and phrenology, both European sciences of the body that gained enormous popularity in the United States in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, were new and old at once: although both employed new empirical methodologies of natural science to posit direct connections between observable body parts and character traits, they were both also building on centuries of interest in the relationship between a body’s visible exterior and its hidden interior.

Since the fourteenth century, Europeans had largely understood this relationship between body and character through the theory of humoralism: the belief that each body contained within it four fluids (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile) called humors, and that an individual’s specific balance of these humors directly shaped not just their health, but also their behavior and the appearance of their body.

So connected were the exterior and the interior that, as historian Sharon Block has written, as late as the eighteenth century “writers might interchangeably use ‘complexion,’ ‘constitution,’ and ‘temperament’ to explain the collection of humors that characterized all living creatures,” even though these three terms are understood to be completely distinct today. Thus, the contribution of the men who formalized physiognomy (Johann Lavater) and phrenology (Franz Josef Gall) was systematizing a broader humoral worldview about the connection between body and character, and giving it the prestige of modern science.

What has not been sufficiently appreciated, however, is that the same systemic analysis of the exterior body’s flesh-and-bone parts that fueled physiognomy and phrenology in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries also extended to the hair. To be sure, even under the humoral system, hair could be used as evidence in diagnoses of the balance of fluids. There is even residue of this perspective in the hair taxonomy with which this book opened, which included the assertion that white hair indicated a “lymphatic” body. (Lymphatic is analogous to humoralism’s buildup of black bile.)

Yet before the eighteenth century, Europeans—including the English people who colonized North America—did not conceptualize hair as an integral body part. Hair was, instead, discharge: like semen, breastmilk, vomit, and urine, hair was a form of waste matter excreted by the humoral body.

In fact, some seventeenth-century writers even used the word excrement to describe human hair. The English writer William Prynne, for example, referred to hair as “Hairie excrements” or just “their Excrements,” and to periwigs—a style he loathed—with the colorful (and completely repulsive) phrase “powdred [sic] bushes of borrowed excrement.”

That hair lay outside the boundaries of the human body was even more clearly emphasized in Welsh historian James Howell’s 1645 travel memoir. Anticipating that his readers would not believe his claim that his hair had changed color during his travels away from England, Howell wrote, “but you will say that Hair is but an excrementitious thing, and makes not to this purpose.”

Howell’s seventeenth-century contemporaries, as subscribers to humoralism, likely did understand the human body to be vulnerable to change when one’s environment changed; this environmental framework explained, for example, differences in skin color in different parts of the world: people who lived in hotter climates were presumed to have darker skin because of that climate. However, because hair was not considered part of the body under humoralism, Howell’s claim that environmental change also changed his hair would likely have been received with the very skepticism he anticipated.

For the first century of English colonization of North America, then, European-descended people largely understood hair to be beyond the body’s boundaries. Hair did carry meaning, but in a different way than emerged in the eighteenth century. Seventeenth-century colonists believed that hairstyling—such as its ornamentation and its length—offered important evidence of a person’s social identity.

The way a person styled their hair could indicate their social status in their community, such as whether they were an elite. It could also indicate their religious identity: an English Puritan man who wore his hair long, for example, communicated to his fellow Puritans that his adherence to his faith had lapsed. Yet, importantly, the fact that English colonists accorded significance to specific hairstyles did not mean they defined the hair as a body part.

The history of scalping demonstrates precisely this point. Scalping was a form of wartime trophy-taking practiced by some Indigenous tribes, who understood the hair (and attached skin) they collected to be a powerful body part—one that carried with it the scalped person’s spirit. In the late seventeenth century, colonial New England’s leaders appropriated scalping into their own legal codes in the form of bounties paid for the scalps of enemies.

It is easy to assume that colonists’ adoption of scalping meant that they, too, adopted the same kinds of bodily meanings attributed to the shorn hair. However, English scalp bounties made scalping purely transactional: they divorced an Indigenous practice (the act of removing the hair from the scalp) from its original meaning (that to remove the hair was to remove a part of the body). English scalping did not, in other words, undermine their understanding of the meaning of hair as beyond the boundaries of the body.

The meaning of hair began to shift in English North America in the eighteenth century. As humoralism eroded and natural science emerged, hair was increasingly understood not as excrement, and not as meaningful only for its styling—instead, hair’s biological nature and biological features became increasingly significant to the way European-descended people conceptualized hair.

Firmly in place by the early nineteenth century was an understanding that hair was a part of the body, and with this sense of hair’s corporeality came a growing emphasis on the significance of its biological qualities, such as color, texture, and thickness. These qualities, moreover, became increasingly significant as markers of gender and racial difference.

The importance of hairstyles did not disappear from American culture, but even some hairstyles became increasingly subject to claims of biological inevitability: white women grew long hair naturally, and white men grew full beards naturally. Hair was increasingly believed to offer nineteenth-century Americans the same kind of empirical reliability and prestige as other forms of body science.

Hair was increasingly believed to offer nineteenth-century Americans the same kind of empirical reliability and prestige as other forms of body science.

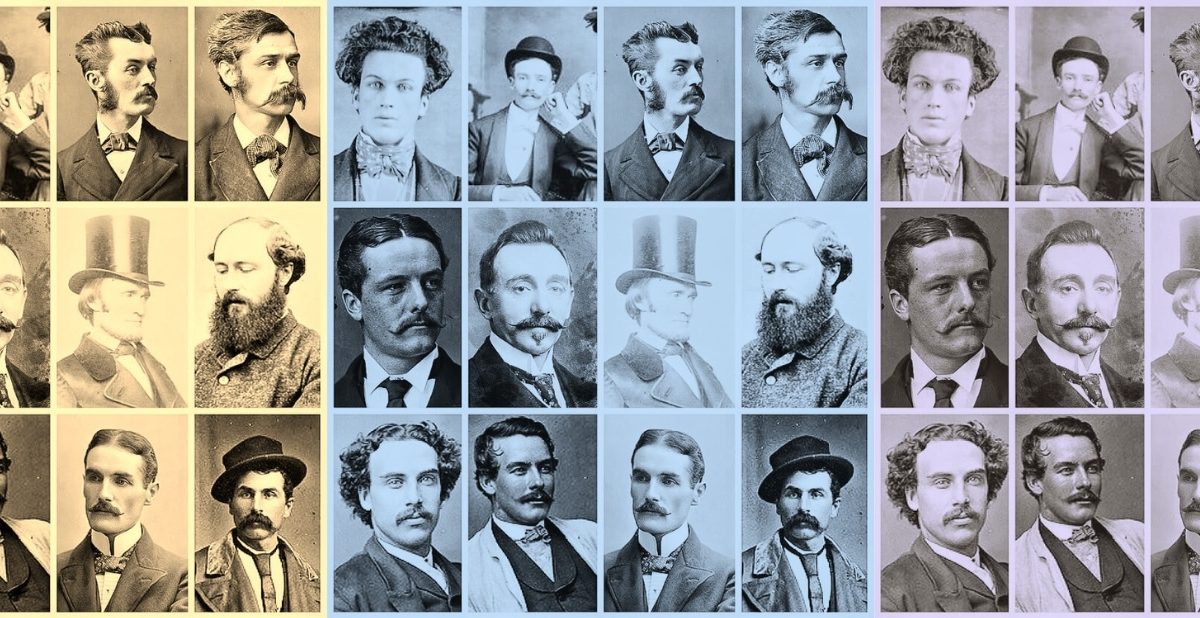

For example, a New Orleans journalist named Dennis Corcoran asserted in 1843 that, “if properly and practically understood,” a person’s hair “would as unerringly indicate character as either physiognomy or phrenology.” Corcoran outlined a taxonomy specifically for facial hair: “With large and naturally glossy black whiskers,” he wrote, “we always associate honesty of mind and firmness of purpose,” while “a moderately sized crescent-formed whisker” indicated “good nature and a tolerable share of self-esteem,” and “a short, ill-shaped whisker, an inordinate love of riches and penuriousness.”

Corcoran told readers that this classification system could, in fact, be a new branch of natural science—a science he dubbed “whiskerology.” In Philadelphia, a lawyer and scientist named Peter Arrell Browne set out to develop just such a science, though he referred to his work as trichology, trich- derived from the Greek etymon for hair.

Using experimentation, precise measurement, and microscopic analysis, Browne argued that hair science had the power to reveal racial truths, especially when other bodily characteristics, such as skin color, were ambiguous: the shape of a single strand of hair would, he argued, reveal a person’s authentic racial category, no matter how they presented in public. To Corcoran, Browne, and many of their contemporaries, there was no body part more reliable than hair.

Although Americans generally understood hair to be part of the body during the nineteenth century, they also reckoned with the fact that hair is still different from other body parts in several important ways. Unlike the bones and soft tissues, hair can withstand extreme levels of manipulation; it can also be separated from the body painlessly, retaining the same color and texture it had when it was attached to the body, and usually resisting decay for decades or longer.

Nineteenth-century Americans saw, understood, and documented these differences. For example, when a girl named Margaret E. Smiley added some of her hair to her friend’s hair album—a book for collecting locks of hair—she penned a poem alongside that began: “There is a lock from the giver[’]s brow / Which will retain its usual hue / When she is absent from your face.” Mark Campbell, a hair-work artist from New York, took this sentiment even further when he claimed that hair had been “found on mummies, more than twenty centuries old, in a perfect and unaltered state.”

Charles Ball experienced this type of arresting scene firsthand. In his narrative of his life while enslaved, Ball described entering a wealthy Maryland family’s vault, where he saw “more than twenty human skeletons, each in the place where it had been deposited by the idle tenderness of surviving friends.” One pair of skeletons in particular moved Ball the most: “a mother and her infant child,” lying within a single coffin.

His description of these two figures emphasized their decay: the mother wore gold rings “on the bones of the fingers,” earrings “lay beneath where the ears had been,” and a necklace “encircle[d] the ghastly and haggard vertebrae of a once beautiful neck”; even the coffin was “so much decayed that it could not be removed.” Yet despite this overwhelming deterioration, the hair remained unspoiled.

As Ball wrote, “the hair of the mother appeared strong and fresh. Even the silken locks of the infant were still preserved.” When the entire body and even the box intended to house the dead had withered away, the hair remained as “fresh” as it had been in life.

Nineteenth-century Americans did not simply notice hair’s unusual properties. The unique materiality of hair, relative to the rest of the body, provided the very basis of its meaning. An 1855 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book, the most popular women’s magazine of the nineteenth century, captured precisely this significance:

Hair is at once the most delicate and lasting of our materials, and survives us, like love. It is so light, so gentle, so escaping from the idea of death, that with a lock of hair belonging to a child or friend, we may almost look up to heaven and compare notes with the angelic nature—may almost say: “I have a piece of thee here, not unworthy of thy being now.”

This description echoes in the letter a New Jersey woman—sentenced to death for murdering her mother—sent to her husband from prison in 1812. Enclosed in the letter was a lock of her hair that she instructed her husband to save for their infant son; this lock, she wrote, was “a part of [the baby’s] poor unfortunate mother,” and thus “will stand as a living monument of my wishes, when worms are devouring my skin and flesh.”

To this woman— and to the hundreds of thousands of other Americans who wrote about, talked about, and preserved locks of hair—hair was incomparable to any other part of the body.

Hair’s unusual properties made it particularly significant to nineteenth-century Americans anxious to find specific meaning in the physical body—the same drive for meaning that made body sciences like phrenology and physiognomy so popular in the same era.

Phrenology even sometimes incorporated hair into its evaluations of the head, such as the explanation, in the popular Illustrated Self-Instructor in Phrenology and Physiology (1857), that “coarse-haired persons should never turn dentists or clerks, but should seek some out-door employment,” whereas “dark and fine-haired persons may choose purely intellectual occupations, and become lecturers or writers with fair prospects of success.” (This dark-haired lecturer and writer has no comment.)

Yet hair is also different in one crucial way from the skulls that formed the evidentiary basis for phrenology, as well as other parts of the body that have historically carried racial meaning: it is extremely capable of change. Some phrenology enthusiasts—including many Black intellectuals at midcentury, who sought to use phrenology to challenge the rigid racial hierarchies of mainstream racial science—did argue that education and mental cultivation could change the shape of the brain.

A new brain shape would, in turn, transform the shape of the head, thus altering a person’s phrenological profile. But even those who believed that changing the shape of the head was possible admitted that it would be a slow and uncertain process without a predictable roadmap.

Hair, by contrast, could be changed in an instant. It has a unique capacity for easy and immediate manipulation—alterations that could be performed by almost anyone, on demand, and, in many cases, as easily enacted as reversed. These characteristics made hair’s potential for destabilizing and ungovernable play greater than any other part of the body.

Hair’s capability for change made it different from the body’s flesh-and-bone features, but nineteenth-century Americans understood that hair was also different from the objects they used to cover or adorn their bodies. For all its malleability, hair is not entirely of the wearer’s choosing, unlike clothing, hats, jewelry, and other accessories.

Hair is, at once, neither completely rigid nor completely plastic. It is biological—as nineteenth-century Americans increasingly emphasized—but it is also cultural.

This middle position between fixed and flexible made some Americans uncomfortable; it made others ambivalent about whether hair had any fixed meanings at all. Indeed, hair’s meanings in American culture were not always stable, and people did not always agree on a universal taxonomy or code for what each specific color, type, or texture meant.

But this capaciousness is precisely what gave hair its power: it could be a tool for marking the bodies of who was, or who had the potential to become, part of the American body politic—but, with a modification as simple as a haircut or a false mustache, it could also be a tool for subverting existing power structures or redirecting them in subversive ways.

By tracing both parts of this story—the regulations (and forms of violence) that tried to manage the hair on certain kinds of bodies, and the contexts in which Americans played with or took advantage of hair’s malleability—this book demonstrates the important role that hair played in defining, policing, and contesting the borders of belonging in the nineteenth century. In an era of such rapid and enormous change, the characteristics that defined an American, an American body, and, therefore, American citizenship itself were unstable and uncertain.

Hair was uniquely powerful because it could do two things at once: it could offer certainty to those who wanted certainty, and it could offer transformation to those who wanted transformation.

That there were racial and gender facets to American identity was obvious to most Americans by the early nineteenth century, but how to locate those facets in the body was not. Hair was uniquely powerful because it could do two things at once: it could offer certainty to those who wanted certainty, and it could offer transformation to those who wanted transformation.

Bodies of all kinds sought access to, and challenged each other’s claims to, American citizenship—and hair became a lightning rod for all of it.

Whiskerology: The Culture of Hair in Nineteenth-Century America by Sarah Gold McBride is available via Harvard University Press.