Women’s studies programs in the United States are threatened by authoritarian pressure. For example, the Ohio legislature restricts how marriage and abortion can be presented in the college classroom, while the Florida state government took over a public college and abolished its gender studies program. At the federal level, words including “gender” and “women” are banned from government agencies and flagged for suspicion in scientific grant applications. Behind such moves is the implicit claim that women’s studies doesn’t belong in educational spaces because it is ideologically monolithic.

Women’s studies programs have long been under threat from erstwhile supporters who now deem them irrelevant. Former University of California, Berkeley, chancellor Carol T. Christ, who once campaigned for women’s studies, stated in a 1996 lecture, “The use of gender as a focus of analysis has become so pervasive throughout the humanities and social sciences that I occasionally wonder whether the idea of a discipline that bounds the study of women is adequate to the wealth and variety of work being done.” Christ’s comment reflects how far Berkeley has come since 1970, when an Academic Senate Report revealed that around 4 percent of tenured faculty members were women.

More recently, in 2024, the University of California, Santa Cruz, announced that it would disband its Feminist Studies Department after faculty members felt drawn to “other pursuits.” The 50-year-old department is among the first of its kind.

Analogously to the disappearance of women’s lands that we discuss in a previous article, the diminished urgency of women’s studies might seem to suggest that feminism has transformed mainstream society so drastically that separate spaces are no longer needed.

Contradicting this idea that feminism is no longer relevant, gendered rhetoric is now a primary mode of bolstering state power. Insidiously, feminist language is being reappropriated to justify the erasure of feminist ideas and feminist history. Most notably, an executive order censoring “gender ideology”—the very idea that “woman” is not a “true and biological category”—does so with the alleged aim of protecting “intimate single-sex spaces and activities designed for women.” The second wave feminist concept of separatism, women’s divestment from men and from patriarchy, was once a radical rejection of masculinist power. Now, it is being used to uphold state authoritarianism.

As a feminist collective, we—three Bay Area locals inside and outside academia—were faced once again with the question of how to inherit the legacies of early feminist activists in a shifting present. Now, we wondered how the university’s institutional context expanded and limited the radical possibilities of feminist collectivism.

This past winter, we looked to the Berkeley Women’s Studies Movement Archive at the Bancroft Library for answers. This archive charts the history of women’s studies at Berkeley from the late 1960s among comparative literature graduate students, to the 1970s and ’80s among undergraduates and faculty, to its 1991 formal investiture as a department. Since 2005, it has been known as the Gender and Women’s Studies Department.

Some might believe that the history in these archives of conflict between radical feminist organizers and university administrators underscores the difficulty of moving the horizontal, communal structure of the feminist collective into the hierarchical, individualistic structure of the modern university. Instead, we realized that the existence of conflict justifies the place of women’s studies within the university. Conflict is necessary to the continued existence of all academic disciplines: scholars disagree with one another, and out of this disaccord, previous theses are amended, others defended; and new theories, axioms, and ideas are born.

Conflict, in other words, is essential to the history of feminism, to the history of the university, and to the history of democracy. Authoritarianism, by contrast, perpetuates itself through manufactured consensus. As writers of feminist history, then, our best tool against authoritarianism’s appropriations of feminist language is telling a feminist history that highlights conflict. Doing so makes it harder to boil down feminism into uniform slogans, the sort that can easily be retooled and wielded against feminist liberation.

Figure 1. Cover letter from Comparative Literature Graduate Women’s Caucus on MLA report, sent to department, December 4, 1973, Judy Wells papers, BANC MSS 2017-102, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Before there was a formal women’s studies department at Berkeley, there was the informal Comparative Literature Women’s Salon. PhD student Marsha Hudson founded the group in 1969, so as to counteract the maleness of the literary canon she encountered in graduate school. “The anguish was so profound,” she remembers in her 2005 essay in The Berkeley Literary Women’s Revolution, “that my ability to continue to study a literature written by and for men was called seriously into question.” The salon’s goal was to address the patriarchal assumptions embedded in academia by reading and discussing literature written by women.

Many of salon’s first members were involved in “consciousness-raising” groups beyond the university and saw the salon as a continuation of that endeavor. Consciousness-raising was a form of activism: women articulated their individual experiences of dissatisfaction to create a shared identity based in systematic gender-based oppression. This enterprise reflected the “collective” as a central organizing concept in the nascent women’s movement, comprised of haphazard groups in which a lack of hierarchy was considered essential to the deconstruction of patriarchal hegemony. As Pamela Keaton theorized in a 1970 essay, “The group through its many individuals working together creates an interpretation and then stands collectively behind it,” and the very “existence of the space reawakens the will to act.” Collective interpretations achieved through consciousness-raising were supposed to generate concrete emancipatory action.

The salon’s focus on reading and discussion gave way to curricular change. In spring 1972, the group successfully lobbied for the comparative literature department to offer its first class on women writers.

Figure 2. Draft proposal for a group major in Women’s Studies with Gloria Bowles’s handwritten note to Judy Wells, April 15, 1974, Judy Wells papers, BANC MSS 2017-102, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Undergraduates played a central role in developing Berkeley women’s studies. In 1973—just one year after comparative literature PhD students successfully pressured their department—undergraduate Ellen Carleton declared that she wanted to major in women’s studies. By this point, however, such a major did not exist.

By April 1974, a collective of undergraduate students and faculty, the Women’s Studies Committee, submitted a proposal for a “group major,” cobbling together courses across departments. Against the collectivity that infused the women’s movement, the 1974 proposal draft emphasized how women’s studies would benefit individual students. Reiterating “a truism of liberal education that to know oneself is a prerequisite to participation as a useful member of the community,” the draft touts the “increased self-confidence” and “improved self-image” that students—assumed here to be only “young women”—would obtain from women’s studies.

The proposal was rejected twice. It was finally accepted one year later, in fall 1975—but only with the stipulation that the organizers add a zoology course to include the “other side.”

In fall 1976, women’s studies became a program, with two core courses and a designated coordinator in Gloria Bowles, lecturer and comparative literature PhD graduate. When the program opened its doors in Campbell Hall, its hallmark was interdisciplinarity: the sharing of knowledge across traditional disciplinary borders. This was partially pragmatic. Administrators housed women’s studies under the Division of Interdisciplinary General Studies with other programs that—Bowles recalled in a 2021 oral history—“the university didn’t know what to do with,” like environmental studies. Because women’s studies was not a department, it lacked tenure-track faculty. Consequently, it needed to borrow professors from other disciplines. A women’s studies major in the 1970s would have found herself taking classes across the sciences, social sciences, and humanities, an education in structures of knowledge that few other majors offered.

Soon, women’s studies questioned its own governance structure. The archive records tense conversations between Bowles and her students—half of whom, Bowles remembers in her 2009 memoir, Living Ideas, were returning students around her own age who identified as lesbians and had organizing experience in the women’s movement.

While the archival documents we examined record tensions between feminism’s collective ethos and the university’s hierarchical structure, at a deeper level, women’s studies emblematizes the university’s central tenet: that knowledge-making is an outcome of contention, not conformity.

In August 1977, undergraduates calling themselves the Women’s Studies Caucus served Bowles a letter decrying “the current imbalance of power in women’s studies” and asserting, “We want the Women’s Studies Board to be collectively structured so that no one person has more power than another. Everyone in the group should be open to this collective process.” Bowles’s frustrated marginal scrawl reads, “How is this imbalance manifested? What is power? What power do you want that you don’t have?”

That same year, the caucus crafted “Principles of Unity” condemning the program’s structure as “contradictory to the ideas which we, as feminists, have come to value.” They demanded “student-led classes”; diverse hiring practices; syllabi including “third world, lesbian and working class women”; and a “field work” component, awarding academic credit for feminist organizing outside the university.

The caucus successfully campaigned for a Women’s Studies Board on which faculty and undergraduates had equal say over the program’s governance. While in theory this structure should have produced egalitarian decision-making, in practice the board was sharply divided between undergraduate and faculty opinions, with students on the board outnumbering faculty. In summer 1978 Bowles proposed that she should have veto power over the board’s decisions, leading the students to stage a walkout in protest.

These tensions paralleled an existing ideological divide in the women’s movement, which Jo Freeman described in an article in 1974. On one side were those who supported “reform” and “women’s rights,” and on the other were those who identified as “radical” and campaigned for “women’s liberation.” The former emphasized a “top-down” approach, “with elected officers, boards of directors, bylaws, and the other trappings of democratic procedure,” whereas the latter leaned into the amoebic structurelessness of the collective, influenced by the radicalism of the civil rights and antiwar movements.

An undated, typewritten note in Bowles’s papers, sandwiched between two stapled pages, illustrates the board’s psychological toll on Bowles: “what I learned—inability to get angry when the situation really demands it, to serve others instead of looking out for myself better, accepting my power: having trouble beingan [sic] authroity [sic] and then being taken advantage of by students who sense my ambivalence (the good students use that openess [sic] to be creative but immature students use me …).”

Early women’s studies organizers may have initially indulged a utopian aspiration of seamless consensus. But the archive betrays a reality of bitterness and dissent.

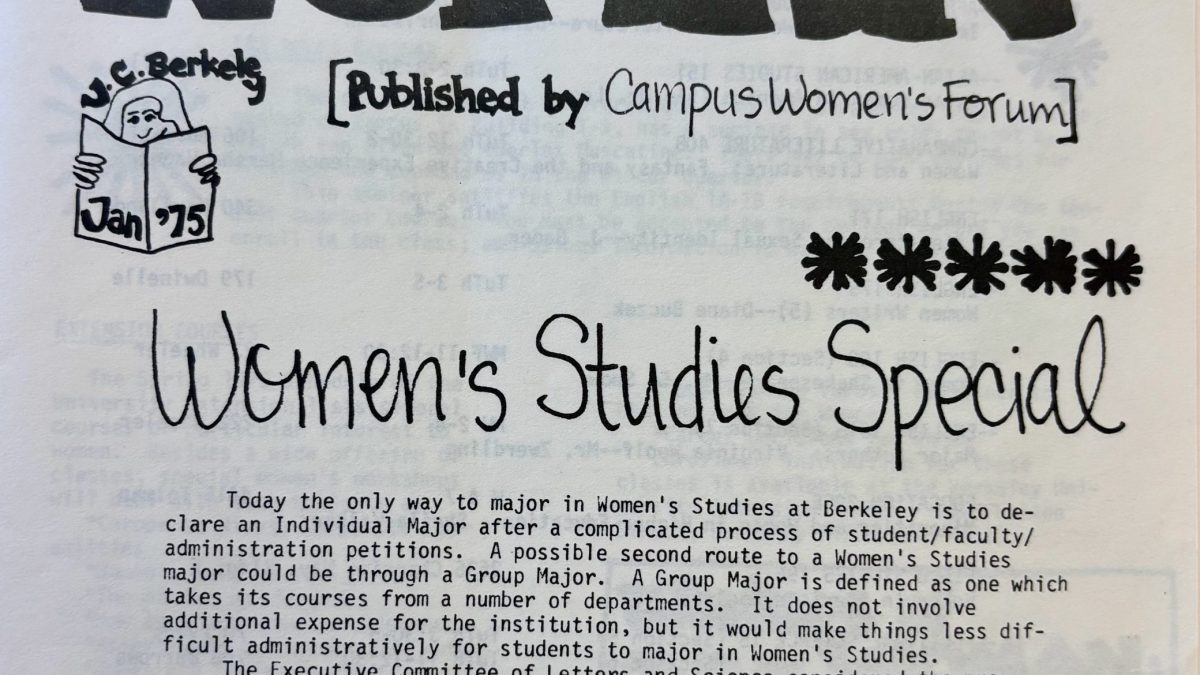

Figure 3. Women’s Studies Special, January 1975, Gloria Bowles papers, BANC MSS 2017/118, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Women’s studies classrooms in the 1970s were not homogenous; students differed in their political leanings and opinions about how classes should be conducted. In a course survey, students were asked to express their expectations anonymously. Substantial variations emerged. One student hoped that “this will be a radical class and deal with separatism, feminism and lesbianism,” while another expected “the course will be like a consciousness-raising group.” Among such aspirations for a classroom with a radical feminist structure were expressions of hesitancy about feminism’s radical elements. One student did not want this “to be a [sic] I-hate-men course.”

After teaching the 1977 intro course, Christ characterized the classroom as a space of “considerable hostility and distrust” that was “exacerbated, perhaps even created, by the divergent political views—between lesbian and straight, radical socialist and more conservative students.” She concluded, “That the conflicts the class exhibited are fundamental to the women’s movement itself did not make the problems of the class any easier.”

The debates about governance on the Women’s Studies Board reappeared in the classroom as clashes between students advocating “feminist pedagogy” and the hierarchical structure of teaching. In 1981, most members of the senior thesis course wrote to their professor, lecturer Dorothy Brown, grieving “the definite absence of a feminist method in the structure and teaching” of the course. “Feminist method” included, among other things:

- A non-hierarchical relation among students and instructor

- Collective participation and criticism, evaluation and grading of each others’ work […]

- Emphasis on the process of thesis-writing as the development of ideas and research methods as well as emphasis on the product […]

- Supportive atmosphere created by all participants for our work, ideas, and emotions

Borrowing from the collective form of the feminist manifesto, the students forcefully positioned themselves as a unit with “common problems” and demanded change. Also writing together, Bowles and Brown rebuked these grievances as emblematic of “the tensions and paradoxes of conducting a feminist classroom within the constraints of the university setting.” Positioning student demands as logically inconsistent, they highlighted the limitations of viewing the classroom as a transposition of the consciousness-raising circle.

In 1983, in the wake of this and other conflicts, the university decided the women’s studies program should be chaired by a tenured faculty member and replaced Bowles with Carolyn Porter of English, who had no previous knowledge of women’s studies. Bowles remained as an instructor.

Figure 4: Comparative literature PhD graduates, June 1976. From left to right are Gloria Bowles, Judy Wells, and Olivia Eielson. Photo courtesy of Judy Wells.

During the 1980s, debates about a “reform” versus “radical” women’s movement reemerged in altered form. Now it was a conflict between advocates of “integrated” women’s studies, who supported incorporating knowledge about women into existing disciplines, and proponents of “autonomous” women’s studies, who began imagining women’s studies as a stand-alone department. In the introduction to their 1984 volume Theories of Women’s Studies, Bowles and Renate Klein landed on the autonomous side. “To introduce feminist insights means to challenge radically the generation and distribution of knowledge; it means changing the whole shape of the course, or the problem—or the discipline,” they write. “Advocates of autonomous Women’s Studies and integrationists thus work from different assumptions: the integrationists hope to achieve the transformation from within the very framework which we believe needs transforming.”

Opposing autonomy were Berkeley administrators who used the language of integration to continue withholding resources from women’s studies. In April 1982, a letter to Bowles from a faculty committee tasked with reviewing women’s studies asks, “Would it not be more effective to ‘redress the imbalance in the University curriculum’ by having courses in women’s studies integrated with departmental offerings rather than as part of an independent program?” In July, the committee wrote again, deeming it “premature to consider the possibility of departmental status for Women’s Studies” since “departments are increasingly accepting the importance of women’s studies to their disciplines.”

Against this cynical mobilization of integrationist rhetoric, throughout the 1980s, Berkeley women’s studies organizers increasingly advocated for the autonomy that departmentalization offered. In her 1984 Report on Women’s Studies, Porter summarizes, “When Women’s Studies programs were first established 10-15 years ago, many of them expected simply to correct an imbalance built into the existing curriculum. Once this was accomplished, Women’s Studies would, like the state in Marx’s theory, wither away.” Porter argued the opposite: because women’s studies reshapes the very forms of knowledge-making that traditional disciplines encompass, it demands its own separate department.

In 1985, tensions between students, faculty, and administrators—with Bowles positioned in the middle—reached a crescendo, leading to Bowles’s ousting from the program. A May 9, 1985, exposé in the Daily Cal, entitled “Well-known feminist scholar isn’t rehired,” includes a quote by Sarah Lutes, a women’s studies senior. Lutes says, “This proves that women, especially feminist women on campus, can’t count on each other.” Bowles did not remain at Berkeley to see women’s studies achieve departmental status in 1991.

As we were writing this article in spring 2025, the US government situated ethnic studies programs at the center of its ongoing attacks on higher education. On March 21, 2025, Columbia University stated that it would place its Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies Department under “academic receivership,” with the goal of recovering $400 million dollars in federal government funding. On March 28—ahead of an announcement that the government is reviewing $9 billion dollars in funding contracts with Harvard University—leaders of its Middle Eastern Studies Center were asked to step down.

One might see the fate of ethnic studies as analogous to but separate from the fate of women’s studies. Yet the archives show that Berkeley’s women’s studies never could have existed without the inspiration of the hard-fought institutional acceptance of ethnic studies.

Women’s studies organizers modeled their movement after the earlier, militant movement to establish ethnic studies, in which some of them had also participated. Minutes from early women’s studies meetings repeatedly express a desire to emulate ethnic studies. Ethnic studies was more than an example; some women in ethnic studies shared their newfound expertise with women’s studies. Barbara Christian, a scholar of Black women’s literature and a founder of Berkeley’s African American Studies Department, was one of the most active faculty members in early women’s studies organizing.

At worst, invocations of ethnic studies implicitly drew simplistic parallels between racism and patriarchy; as Bowles notes in Living Ideas, in the early years of women’s studies, “all our students were women and white.” At best, they envisioned a coalition between those traditionally marginalized by the university’s curriculum.

It was ethnic studies that endowed women’s studies organizers with optimism that the university could be a site of radical political possibility. Supporting women’s studies requires denouncing the authoritarian pressures that ethnic studies is facing.

Figure 5. Members of the Comparative Literature Women’s Salon, 30 years later. In the top left is a group shot with Berkeley Literary Women’s Revolution in 2005. In the back row, from left to right, are Doris Earnshaw, Marsha Hudson, and Judy Wells; in the front row, from left to right, are Olivia Eielson and Bridget Connelly. The remaining photos depict individual members signing the contract for Berkeley Literary Women’s Revolution in 2004. In the top row, from left to right, are Bridget Connelly and Doris Earnshaw. In the bottom row, from left to right, are Marsha Hudson, Judy Wells, and Olivia Eielson. Photos courtesy of Judy Wells.

The organizers of Berkeley women’s studies saw consensus as a feminist goal. Yet this dream of consensus is belied by the archival record of continuous disagreement.

The organizers who first envisioned women’s studies as an academic discipline disagreed over almost every aspect of what this discipline ought to be: who it was for, how it should be governed and taught, what methodologies and epistemologies it should accommodate. Where they went wrong was not in disagreeing but in believing that conflicts should be assimilated into consensus.

The strongest argument for the continued place of women’s studies in the university is its internal heterogeneity. While the archival documents we examined record tensions between feminism’s collective ethos and the university’s hierarchical structure, at a deeper level, women’s studies emblematizes the university’s central tenet: that knowledge-making is an outcome of contention, not conformity.

The best example of consensus occurs not in the archival record itself, but in Judy Wells’s 2023 history of the founding of the archive itself. Wells, an early member of the Comparative Literature Women’s Salon, says that in contrast to “our feminist history [that] was sometimes fraught with conflict,” the women who contributed to the archive “worked together as a team” to see it into existence. By that time, five decades had passed between the salon’s founding in 1969 and the archive’s founding in 2019. What had changed? Perhaps consensus comes with time.

Or perhaps the organizers came to recognize that a crucial history would be lost if the record of their arguments and fractures were not preserved—if, from our present vantage point, we looked back at women’s studies, or the women’s movement from which it derived, as monolithic, or even as inevitable. And perhaps, in creating an archive, they acknowledged that the enduring fight for women’s studies was not only, or no longer, their own. ![]()

This article was commissioned by John Plotz.

Featured image: Women’s Studies Special, January 1975, Gloria Bowles papers, BANC MSS 2017/118, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.