During colonial times and in the days of the early republic, frontier folk were disdained by the guardians of American culture (such as it was) as dangerous characters of low breeding, prone to democratic anarchy and fits of violence. Politics were controlled by the elites of New England and Tidewater Virginia.

Article continues after advertisement

Then, in the 1820s, Americans began to search for a distinctive identity separate from their European ancestors. The powerfully symbolic deaths of both Thomas Jefferson and John Adams on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1826) was a major impetus, for the new generation felt keenly the passing of the Revolutionary generation (not unlike the present uneasiness at the passing of the World War II generation). Americans turned to the West in search of new figures to lead the country forward—men who were masters of both a hostile environment and their own destiny.

As the Western story triumphed on all fronts, it was increasingly burdened with a melancholy nostalgia. The West was won; now what?

The success of James Fenimore Cooper’s “Leatherstocking Tales,” and most notably his Last of the Mohicans in 1826, along with Timothy Flint’s acclaimed biography of Daniel Boone in 1833, helped to create a literary ideal of the American frontiersman as well as encouraged a successful series of “border dramas” on the stage, such as Nick of the Woods and The Lion of the West (based on Davy Crockett).

At the same time the rise of Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, Sam Houston, Crockett, and other Westerners marked a shift in political power from the East to the New West and ushered in the so-called Age of the Common Man. The martyrdom of Crockett at the Alamo, the celebrated explorations of Kit Carson and John Charles Frémont, the epic migration to Oregon (immortalized by America’s first great Western historian, Francis Parkman, in his 1847 Oregon Trail), all served to idealize the bold frontiersmen as representative of what an American should and could be. Samuel Woodworth’s popular 1822 song “The Hunters of Kentucky,” in which, at the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, the Kentucky and Tennessee frontier soldiers were all “half a horse, / And half an alligator,” became a campaign ditty for Andrew Jackson. The 1828 election of Jackson marked the culmination of the rise of a new America.

At the same time that Americans celebrated these new frontier heroes, they followed Cooper’s lead in lamenting the tragic fate of Indian leaders such as Pontiac, Red Eagle, and Tecumseh. Jefferson’s dream of a peaceful merging of the two races was forgotten as greed for land led to a policy of separation, removal, and segregation. Ironically, all of the foremost frontier figures—Boone, Crockett, Carson, Cody—sympathized with and defended the Indians, sometimes even while fighting them. In time they came to see that they often had more in common with their Native foe than with the people of the East who brought on conflict. The story of the West is a tale of contradictions and irony.

Jackson’s protégé, the underappreciated James K. Polk, quickly fulfilled Jefferson’s “Empire of Liberty” dream by seizing the American Southwest and California from Mexico, acquiring the Oregon Country, and achieving the nation’s continental “Manifest Destiny.” A ghastly Civil War rent this all asunder until another Westerner redeemed the dream, restored the Union, and again turned the nation westward. Abraham Lincoln, whose grandfather had followed Daniel Boone through the Cumberland Gap and who had been born in the same year just a few miles from the birthplace of Kit Carson, pushed through the Homestead Act and the transcontinental railroad authorization, which would shape the new trans-Mississippi West.

It is a story of conflict—a heroic tale of the building of a nation always shaded by the dark shadow of racism and violence.

A new epic now arose out of this story that in time united a divided nation and gave a fresh national identity to millions of wildly diverse people from many lands. Printing innovations led to the garish dime novels that horrified parents and literary critics alike. These “penny dreadfuls” celebrated the frontier adventures of a colorful cast of characters, including the hunter, scout, and Indian fighter Buffalo Bill Cody. This story was one of stirring adventure, unbridled optimism, and national progress. When, on May 11, 1887, Cody gave a command performance for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, it seemed as if the United States had finally come of age and that our Western story had indeed conquered the world.

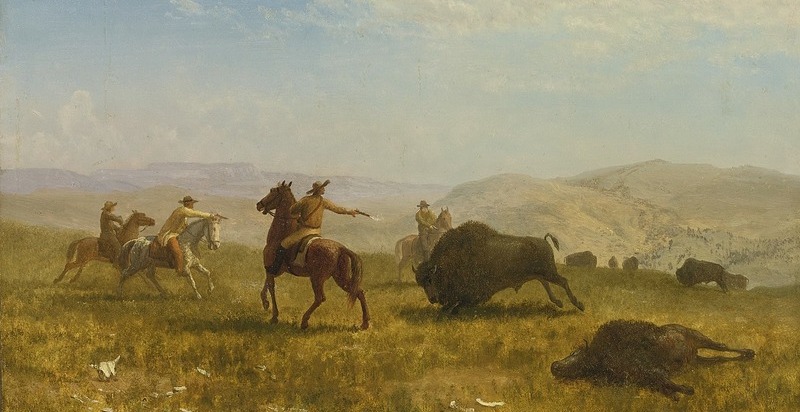

Buffalo Bill, with an able assist from Owen Wister’s 1902 classic The Virginian, along with the art of Frederic Remington and Charlie Russell, enshrined the cowboy (once a pejorative name) as an American icon and made the story of the West America’s story. Theodore Roosevelt, himself the author of the magnificent four-volume The Winning of the West, kept the West front and center as our first cowboy president. The onetime rancher and famed Rough Rider now brought a whirlwind of frontier energy to the White House. His bold efforts at conservation reflected a growing awareness that even at a moment of crowning achievement something important was also being lost. As the Western story triumphed on all fronts, it was increasingly burdened with a melancholy nostalgia. The West was won; now what?

A young historian at the University of Wisconsin, Frederick Jackson Turner, addressed that very question with his 1893 essay “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” which revolutionized the teaching of American history. “American democracy was born of no theorist’s dream,” Turner declared. “It came out of the American forest, and it gained new strength each time it touched a new frontier.” Turner shifted the emphasis of our national story from the East to the West with his bold assertion that the distinctiveness of American cultural and political society, as well as our exceptional national character, emerged from the frontier experience.

He refuted the then prevailing theory that American institutions had evolved from so-called European germ cells without regard to environmental factors. It was the frontier—which he characterized as “the meeting point between savagery and civilization”—that explained the unique American character: a rejection of class and aristocracy, of established religion, standing armies, and the other trappings of Europe in favor of adaptation, innovation, invention, individualism, and a rough-hewn democracy. The frontier was not only a process; it was a state of mind.

In some ways it was all an agreed-upon fable, not unlike the tales of Homer, the legends of King Arthur, or the epics of Charlemagne that provided identity and pride to other peoples. Similarly, embracing the story of the American frontier is what helped make people from all across the globe Americans—and defined who they were as a new people. It is a story of conflict—a heroic tale of the building of a nation always shaded by the dark shadow of racism and violence. “The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer,” observed D. H. Lawrence in 1923 in considering the Western hero. “It has never yet melted.”

Perhaps the Pulitzer Prize-winning Kiowa novelist N. Scott Momaday put it best when he wrote: “It has something to do with legend, and with the way we must think of ourselves, we cowboys and Indians, we roughriders of the world.”

__________________________________

From The Undiscovered Country: Triumph, Tragedy, and the Shaping of the American West by Paul Andrew Hutton. Copyright © 2025 by Paul Andrew Hutton. Published by Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.