Biography

The head that wears the crown

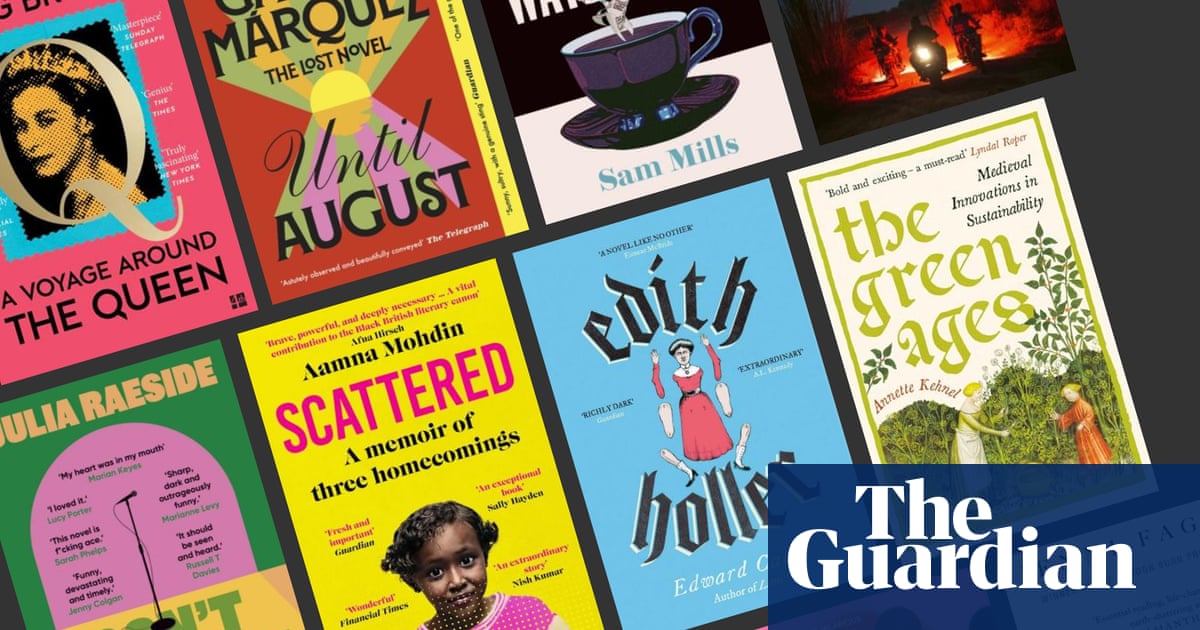

A Voyage Around the Queen

Craig Brown

A Voyage Around the Queen Craig Brown

The head that wears the crown

As Craig Brown recognises, throughout her long reign, Elizabeth Regina was one of the strangest phenomena of what may loosely be called the modern era. Wisely, he does not expend much energy interrogating the conundrum of why she was so significant, and how it was that so many people, not all of them idiots, should have been so preoccupied with her, and why they felt compelled to project their fantasies upon her. She was famous beyond the limits of fame; as Brown informs us, her funeral was watched on television by about 4 billion viewers around the globe, “roughly half the people on the planet”.

In its length and profusion of detail, Brown’s book is almost a match for its subject. He seems to have read everything ever written about the Queen: the list of his sources occupies nearly 15 closely packed pages. After such a sisyphean effort, he is keenly aware of the perils involved. “Reading too many books about the Queen and the royal family,” he writes, “is like wading through candy floss: you emerge pink and queasy, but also undernourished.”

Given his many years as a contributor to Private Eye, it might be expected that his account of the Second Elizabethan Age would have its tongue jammed firmly into its cheek. True, there are many instances of that tone of barely suppressed, schoolboy hilarity the Eye adopts when it has to deal with topics dear to the nation’s heart. Overall, however, Brown gives an astute account of the wellnigh unaccountable public life of an intensely private person who, for most of that life, was on display before the slack-jawed and pop-eyed gaze of millions of total strangers.

John Banville

Fiction

The abandoned last novel

Until August

Gabriel García Márquez

Until August Gabriel García Márquez

The abandoned last novel

“This book doesn’t work. It must be destroyed.” Not a one-star rant from the bowels of Amazon or Goodreads, but rather the verdict of Colombian Nobel laureate Gabriel García Márquez on his now posthumously published novel, Until August, a breezy romp brewed in his 70s and previously excerpted by the New Yorker in 1999 after he read from it on stage in Madrid with the late José Saramago.

An editorial afterword explains how the intimate, decidedly non-epic entertainment now before us – a brisk and frisky tale of extramarital sex doubling as a parable of parental inscrutability – was sewn together from García Márquez’s fifth draft and a document preserving offcuts from prior attempts. The smooth-reading result is the story of Ana Magdalena Bach, who every August leaves her unnamed country on the Atlantic coast for 24 hours on the unnamed Caribbean island where her mother chose to be buried. She takes a ferry to lay flowers on her mother’s grave before returning to her husband – which leaves plenty of time for a yearly one-night stand, as twinkly dancefloor flirtations give way to steamy hotel-room tussles and gnawing regrets played out in comically fraught pillow talk back home.

While the overall ambience might be sunny, sultry, even tipsy, there’s a genuine sting when we learn why Ana Magdalena’s mother – described as a teacher who “never in her entire life wanted to be anything more” – decided she wanted to be buried on the island. Her daughter reckons it was the panorama provided by the cemetery’s altitude – a kind of company in solitude – and ultimately her hunch isn’t so far off the mark. Another jolt lies in the surreal payoff, which is entirely García Márquez’s own, chosen in 2010, his editor states, contra the belief of García Márquez’s agent (cited in the afterword) that her client didn’t have an ending; satisfyingly symmetrical, it lends this gentle diversion the depth of fable.

Anthony Cummins

Fiction

A time-travelling romp

The Watermark

Sam Mills

The Watermark Sam Mills

A time-travelling romp

If you love Doctor Who, you will love this book. It whirls you off on a similarly breathless Technicolor tumble through different eras and genres. But where the Doctor has the Tardis, the two main characters of The Watermark – journalist Jaime and painter Rachel – have cups of magical tea.

The tea is administered to them by Augustus Fate, a bestselling but extremely bitter author, living in rural Wales, who has realised after seven Booker prize shortlistings that his novels lack convincing characterisation and genuine emotion. His solution is to lure two real people to his remote house, and then, by means of the magical tea, to sedate, brainwash and insert them into his stalled work in progress, Thomas Turridge.

However, Jaime and Rachel are gradually able to wake up within Fate’s world. They begin to hear the narrator saying things like, “And so Thomas kissed Rachel and they burnt with a fiery, illicit passion.” Here is where the novel is really clever – because it forces us to read extremely attentively. Each anachronism, everything that fits our world but not Victorian times, is a sign of Jaime’s genuine self struggling to break through. Eventually, with the crashing arrival of a helicopter in the middle of a church service, we get the full world-splitting effect. Fate is thwarted, temporarily at least, and Jaime and Rachel are able to flee into another book – this time set in a poorly imagined 2010s Manchester. Poorly imagined, because its author is their friend and adviser from within the first story, Mr James Gwent, apparently a man of the 1860s but actually an earlier abductee of Fate’s.

This section is one of the novel’s many highlights. Mills has a great deal of fun with the limitations of Gwent’s imagination. When Jaime and Rachel try an excursion to St Petersburg, their flight becomes increasingly sketchy. “I point at the window. The scenery outside has been leached of colour. Our seats are no more than pencil strokes; the view from the window is reduced to a draft.” Three further jumps occur, with the lovers book-surfing to Soviet Carpathia in 1928, to a robot-dominated London of 2047, and one more destination – I won’t spoil things by mentioning the finale.

Toby Litt

Politics

How nationalism changed a country

The New India

Rahul Bhatia

The New India Rahul Bhatia

How nationalism changed a country

Bhatia’s remarkable book is an absorbing account of India’s transformation from the world’s largest democracy to something more like the world’s most populous country that regularly holds elections. It is also a wake-up call to all those who pin their hopes on the institutions intended to safeguard democracy: the bureaucracy, the law enforcement machinery, the media and the judiciary.

By minutely observing the experiences of ordinary Indians – not the ones whose names make it into newspapers for what they have done, but those whose lives are affected by the remarks and actions of pundits who fulminate on India’s increasingly shrill and jingoistic television networks – Bhatia provides a vivid portrait of how a nation turns callous and changes into something unrecognisable.

Friends Bhatia knows from school, relatives, others he has met casually and used to think of as regular people, have begun expressing their bigotry openly, in language they’d once have been embarrassed by. Their views are just that – views – devoid of facts, absent of logic. They are shaped by relentless, biased propaganda parroted over social media by tens of thousands of accounts: if more people say something, it must be true, the recipient believes. And it is difficult, as Bhatia shows, to fight faith with reason, lies with the truth. Reflecting a broader atomisation, he disengages; like many others (not only in India – this is a phenomenon seen also in the United States, where I live, and the United Kingdom, which has been my home) he retreats into his own bubble. And yet, being the fine reporter that he is, he steps out of it in order to understand the other side.

Salil Tripathi

Fiction

More monstrous men

Don’t Make Me Laugh

Julia Raeside

Don’t Make Me Laugh Julia Raeside

More monstrous men

Ali is a radio producer; Ed is a comedian. Ali is vulnerable; Ed is charming. Ali is desperate to be loved; Ed is ready to love her.

And Ed is a predator. Ali is prey.

Julia Raeside’s debut novel begins like a romcom, and ends like a different kind of fantasy: the kind in which people get what they deserve. In between, though, it feels painfully, precisely, beat-for-beat accurate. Sleazy Ed and bedraggled Ali are both so believable you could Google them. Until said denouement, there is nothing here that doesn’t ring absolutely true: famous men behaving badly? Famous men behaving very badly? Famous men taking advantage of their fame, and powerful men taking advantage of their power?

Ali can “remember her first time as a sex object like it was yesterday”, but it doesn’t stop her falling for someone who, from the start, is obviously bad news. Many women faced with Ed’s dismissive, days-later response to a nude shot (“delightful pic x”) might be tempted to block and move on. Ali’s desperate lack of self-esteem may make a certain kind of sense, but it also makes for uncomfortable reading.

Weight is a constant and uneasy preoccupation: Ali charts her own weight loss meticulously, and she observes other women’s bodies with the same laser-focused gaze. Her internalised misogyny makes it difficult, sometimes, to tell this gaze apart from the infamous male gaze. It’s as if the rot goes so deep that the plot frequently comes second to the pain. Does the accurate duplication of suffering act as a tool to dismantle the structures that shaped it, or is it just … more of the same?

No ending, happy-adjacent or not, can shake the feeling that Don’t Make Me Laugh is a novel in which men are monstrous, but other women might be the real enemy. Which is, of course, the patriarchy’s biggest and most dangerous fantasy of all.

Ella Risbridger

Memoir

The road to survival

Scattered

Aamna Mohdin

Scattered Aamna Mohdin

The road to survival

In her first book, Guardian journalist Aamna Mohdin explores her Somali family’s refugee experience in Kenya, Saudi Arabia, the Netherlands and Britain, confronting many different versions of herself in the process. As she rests in a hotel after visiting the Kenyan beach where her mother had landed, heavily pregnant with her, after fleeing the carnage in Mogadishu, Mohdin reflects on a quote from William Faulkner’s novel Requiem for a Nun: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Reading on, she wonders how much of who she is was determined by those events: “All of us labour in webs spun long before we were born, webs of heredity and environment, of desire and consequence, of history and eternity.” Scattered illuminates the webs that entrap not only Mohdin, but countless others who fled the Somali civil war and many conflicts since.

The catastrophe of the war and the humanitarian crisis it created is scarcely written about, and when it is, it’s either politicised or aimed at an academic audience. So the startling honesty and intimacy of this depiction of one family’s chaotic quest to find sanctuary feels fresh and important. All the more so because some of Somalia’s most prominent writers were killed during the war, including the first writer of a novel in Somali, Farah Awl, who was murdered while fleeing Mogadishu in 1991. Movingly, the children born around that time are now piecing this story back together.

Nadifa Mohamed

Fiction

An unsettling fairytale

Edith Holler

Edward Carey

Edith Holler Edward Carey

An unsettling fairytale

The year is 1901, the place is Norwich and the hero of this story is 12-year-old Edith Holler who is, as she tells us, “famous”. Edith lives in a theatre and has never set a foot outside, after warnings that the building will collapse if she leaves. A motherless child, she has grown up among a peculiar selection of theatrical stalwarts – the puppet mistress, the stage door keeper, the prompt – who have lived so long in the playhouse they have become part of it, a strange ecosystem evolved to match their environment, like creatures of the deep ocean.

Edith Holler is, in part, a love letter to the theatre, and one that gleefully embraces a Tim Burtonesque gothic theatricality. Carey, who has worked in the theatre, apparently began writing the book in lockdown when theatres had closed. It is also, more unusually, a love letter to Norwich. The book is steeped in the city’s history, featuring – among others – King Gurgunt, who sleeps beneath Norwich Castle, ready to rise in battle if needed, and the Grey Lady, a famous Norwich ghost. “We may be eastward but we are not backward,” Edith proudly says of her fellow Norfolkians. This is an enjoyably uncategorisable and atmospheric book, a richly dark and idiosyncratic fairytale for grownups.

Joanna Quinn

History

Looking back to look forward

The Green Ages

Annette Kehnel

The Green Ages Annette Kehnel

Looking back to look forward

According to Annette Kehnel, we have forgotten “how to keep an eye on the well-being of the next generation”. In the last 200 years, industrialisation and the economic miracle that flowed from it have brought immense benefits and wealth. But they have also led to microplastics polluting the oceans, and the climate crisis. In order to deal with these urgent problems, Kehnel – a professor of medieval history at Mannheim University – believes we need to look beyond “musty modernity” and rediscover how our ancestors lived so that we can reshape our “outdated short-term economy into a long-term one”.

Although she doesn’t want us to go back to the middle ages, she argues that the period before capitalism offers important examples of how to manage resources both profitably and sustainably. For instance she explores how, over a period of 1,500 years, European monasteries and convents developed “one of the most stable forms of sharing community”. Similarly, during the 13th century, “beguinages” emerged in the urban centres of Flanders. These remarkable female communities were founded by charitable benefactors and maintained by collective commitment. They enriched their towns both economically and culturally, and are “the kind of supportive and empowering community that we might well be inspired to emulate”.

Kehnel also highlights how our cities were once filled with people who mended things: “the modern definition of ‘waste’ as useless leftovers did not enter European dictionaries until the 20th century”. At a time when we need to preserve scarce resources, we could learn from their example and revive our repair professions to make recycling an integral part of our lives once more. From the way microfinance helped to bind urban communities together in the 15th century, to how 12th-century “minimalist communities” who lived by the motto “less is more” can teach us the value of frugality, Kehnel reveals many surprising and fascinating examples that could help us solve the problems of modernity.

This wonderfully original and eye-opening study will transform your attitude towards the medieval period. Through richly researched case histories, Kehnel shows how sustainability was central to the medieval approach to life and that they “knew the limits of our planet better than we do now”.

PD Smith

Fiction

Tea, yoga and sonnets

Practice

Rosalind Brown

Practice Rosalind Brown

Tea, yoga and sonnets

This debut novel follows a day in the life of Annabel, an Oxford student writing an essay about Shakespeare’s sonnets. She wakes and makes tea, works on the essay, meditates, does yoga, works a little more, takes walks, has memories and fantasies, eats in the dining hall, talks to her boyfriend on the phone. The book ends as the day ends. For most of the novel, she’s alone in her room. It is an uneventful day in a safe, cocooned, mostly uneventful life.

The great strength of Practice is Brown’s gift for the romance of the quotidian. Annabel is absorbed by the minutiae of her day: the “building roar” of the electric kettle, the growing pressure in her bladder, her ephemeral lust on seeing lines of muscle sharpening in a passing runner’s calves.

The character of the solipsistic, over-earnest, pretentious, self-consciously ascetic Annabel is brilliantly done. She takes herself too seriously, and knows she’s taking herself too seriously, and takes that too seriously. She takes Shakespeare not only seriously but personally, as only a bookish undergraduate can. Her conception of the love triangle in the sonnets blurs into her own sexual fantasies, then into YA romance tropes before straying on into the weirder outskirts of girlish desire. Like many very young people, she is always performing, just a little bit, for herself.

I both enjoyed and admired this novel. It was mostly a pleasure to travel in a lonely country most people wouldn’t even call story, to dwell in the satisfactions and strangeness of less when it’s just less.

Sandra Newman

Memoir

Spotlight on Generation Xi

Other Rivers

Peter Hessler

Other Rivers Peter Hessler

Spotlight on Generation Xi

Other Rivers: A Chinese Education is a blend of memoir and reportage that chronicles China’s Covid years, often via its young people. We meet Hessler’s curious, ambitious and frequently jaded university students, who stand in contrast to the “young and naive” cohort he recalls from the 1990s. Members of generation Xi, Hessler discovers, “could be brutally honest about themselves, and they entertained few illusions about the Chinese system … They knew how things worked; they understood the system’s flaws and also its benefits.”

Hessler’s compassionate depictions of the conflict between a Communist party seeking to expand its control and an increasingly educated and inquisitive generation have won his writing a band of devotees both inside and outside the country. When he sold his car after being effectively expelled in 2021, it caused a minor social media storm, with users lamenting his departure as the end of an era in which China was open to US perspectives.

Other Rivers implicitly makes the case against both countries turning inwards. When Hessler and his wife, the writer Leslie Chang, arrived in Chengdu, they enrolled their nine-year-old twin daughters in a local Chinese school, despite them barely speaking a word of Mandarin. He documents with an anthropologist’s eye the idiosyncrasies of the Chinese education system, which, despite the hyper-competitive atmosphere, is kept going by teachers whose dedication and compassion holds lessons for western classrooms. And he is full of warmth about the pupils, parents and teachers who, at a time of rising suspicion of foreigners, welcomed his family into their curious, often misunderstood world.

Amy Hawkins

Fiction

Race as performance

Colored Television

Danzy Senna

Colored Television Danzy Senna

Race as performance

Early in Colored Television, 46-year-old Jane Gibson imagines her past self peering through the window of the home she lives in. “Brooklyn Jane” would admire this architecturally interesting house on the hills overlooking Los Angeles, she thinks, and see within it an idyllic scene of family life featuring Jane’s painter husband Lenny – “From a distance, in his horn-rimmed glasses, reading his serious book, he would look like an inspired choice” – and their two children, Ruby and Finn. The vision is warm, sophisticated, “a Black bohemian version of the American dream”.

In this sly novel about dreams, ambition and race as performance, Jane’s fantasy is telling. Because what she carefully edits out are the unlovely truths underneath its gleaming surface: that she and Lenny had been in couples therapy until their money ran out. That Lenny’s paintings don’t sell. That Jane has been toiling over a sprawling novel for 10 years, a “400‑year history of mulatto people in fictional form”, which she must publish in order to get tenure. That her son’s unusual behaviour may merit a doctor’s diagnosis. And, finally, that the beautiful house and its accoutrements don’t belong to them; the family are merely house sitting for Jane’s wealthy screenwriter friend Brett, because the only places they can afford in the greater LA area are “not just overpriced but ugly, smelly, and dark”.

Senna’s novel resists obvious answers, rejects the attempt to neatly package something as complex and ordinary as a human life. Near the end, Jane herself looks through the windows of the house at her family. The view seems “flat, staged, an imitation of life” – the architecturally interesting house, we realise, is itself a sort of gigantic television. But even as Jane grasps that her picture-perfect dreams are hollow, we gain a poignant sense of their source: an unmoored childhood bouncing between her divorced Black father and white mother – a youth spent, appropriately enough, watching TV. It’s a scene that perfectly sums up this allusive, artfully assembled book.

Chelsea Leu

Memoir

A story of survival

Ootlin

Jenni Fagan

Ootlin Jenni Fagan

A story of survival

The Scottish novelist and poet Jenni Fagan wrote this powerful memoir more than two decades ago. It began when she tried writing a suicide note. But it struck her that it “was incredibly sad to think a small assemblage of words” was all that she would leave behind. So she borrowed a typewriter and for weeks sat and smoked and drank coffee, while typing her life story up to the age of 16. Although she vowed never to look at it again, that manuscript kept her alive.

Fagan only returned to it years later. She realised then that Ootlin was “politically more important than anything else I might write”. At its heart, it is “a story about how some stories saved me and others destroyed me”. Fagan spent her entire childhood in care. The government, foster parents and social workers all told stories about her, stories that convinced her that she was “some kind of monster”. Later, when she obtained her social work files, she realised she had been brainwashed into believing the story “that I was the problem”. Fortunately, other stories nurtured her, because this is also about how Fagan escapes from “the unbearable hideousness of life” through the magic of words and books.

Beautifully written, with flashes of dark humour throughout what is a shocking, heartbreaking memoir, Ootlin tells the story of Fagan’s childhood: constantly shuffled between foster parents and kids’ homes carrying a few possessions in bin bags, sleeping rough, raped at the age of 12, a suicide attempt, and escaping it all through drugs: “I stay high because there is a train going five hundred miles an hour next to me at all times and on every carriage there is a memory I can’t bear.” Somehow she survives this childhood, buoyed up by individual acts of kindness from friends or social workers. Incredibly, she also manages to be a “grade-A student” at school, and decides at the age of eight she wants to be a writer.

The winner of the 2025 Gordon Burn prize, this is an astonishing story of survival. Fagan wants it to be a “lighthouse on a distant shore” for others who, like her, are labelled as “ootlin”: “one of the queer folk who never belonged”. Fagan’s important book argues eloquently and movingly that we need to create a society where no child has to live in fear.

- Information and support for anyone affected by rape or sexual abuse issues is available from the following organisations. In the UK, Rape Crisis offers support on 0808 500 2222 in England and Wales, 0808 801 0302 in Scotland, or 0800 0246 991 in Northern Ireland. In the US, Rainn offers support on 800-656-4673. In Australia, support is available at 1800Respect (1800 737 732). Other international helplines can be found at ibiblio.org/rcip/internl.html

- In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on freephone 116 123, or email jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, you can call or text the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline on 988, chat on 988lifeline.org, or text HOME to 741741 to connect with a crisis counselor. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at befrienders.org

PD Smith