During my first semester of teaching in Taiwan, I was in the middle of a lesson on “Monsters and Ghosts” when a student’s hand shot up. His question was not really related to the content: “Teacher, do you think Taiwan is Chinese?”

Article continues after advertisement

All the students, even the co-teacher, turned to see how I’d answer. It was a question I’d been asked many times before, a sudden test of allegiance that would sometimes pop up when I told people that I was Chinese American. The subtext was whether I could be trusted. Usually, the question was couched in politeness, but my students (bless them) had not yet learned to be subtle.

I couldn’t fault them for their curiosity or their suspicion. On the first day of class, I’d drawn a crude chalk map of my world on the board and outlined my movements, from being born in central China to moving to the U.S. at nine. From the beginning, I hoped they’d come to see more complicated versions of Chinese or American identity.

My students also liked to ask which I believed was better—China or the U.S.? I could tell it wasn’t a serious question from their tone, just a way to test my response, so I’d answer flippantly. One time, I lectured them about how these were big, complicated places with lots of different people, though this only led to the student remarking that I sounded brainwashed.

My students also liked to ask which I believed was better—China or the U.S.?

In the fall of 2022, I had just moved to Taiwan to work as an English Teaching Assistant with the Fulbright program. My placement was in the sleepy county of Chiayi in the southwest of Taiwan, far from the tech centers in the north. On the sidewalks, the sounds of Taiwanese Hokkien drowned out Mandarin. During scooter rides to school, I passed low warehouses and rice paddies, where I’d smell the warm tang of crop burn mixed with fertilizer on the wind.

Every class, three or four of the teenage students would be asleep. Some were tired from nights helping out at the family shop, and some had stayed up gaming. When I asked about their weekends, they mentioned claw-machine arcades and the night market. Many didn’t care about grades. As for what they wanted from life, the most concrete answers I heard were to make money or travel to new places.

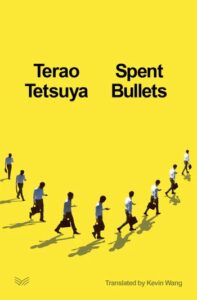

In the early months, I didn’t know how to teach them, though I started to learn more about where I was by reading Taiwanese books. One was Terao Tetsuya’s Spent Bullets, a collection of linked stories about hyper-competitive Taiwanese students who become disillusioned Silicon Valley engineers. Terao’s book resonated with Taiwanese readers, judging by its reviews, podcast discourse, and two Taiwan Literature Award prizes.

Yet the world of Spent Bullets was nothing like that of my students. Its characters were prodigies who had private tutors and went to training camps for programming competitions, though their striving did not add up to a happy life. The book revealed the chaotic, personal truths behind the myths of meritocracy. It also showed a counter-image to the cheerful rhetoric of international exchange through depictions of the messiness and alienation of Taiwanese tech workers in California. The book presented a parallel Taiwan that became a lens for further appreciating the one I was in.

Now I was beginning to feel beholden to a third place, Taiwan, to which I could claim neither blood nor citizenship, where I was a guest.

I had only been living in Taiwan for four months when I met the book’s rights manager, who invited me to translate it. When I first began translating Chinese texts into English in college, the practice bridged my fractured identities: the gap between the “China” where I was born and the “America” I immigrated to.

Now I was beginning to feel beholden to a third place, Taiwan, to which I could claim neither blood nor citizenship, where I was a guest. I had to treat the project with painstaking care, and the translation became a reflection of how I came to Taiwan in ignorance, learning about it as I worked.

In the opening story, the narrator digs in his backpack for his “國文” textbook. A natural translation for 國文would be “Chinese.” Yet I decided to opt for the literal “national language.” In Taiwan, guó 國 (“national”) is attached to many things established by the state, from junior high schools (國中) to freeways (國道). Drawing attention to the word would usually be unwarranted.

But in this case, I thought it was worth preserving a historical reality: the nation-building project of the Kuomintang government, when Mandarin was enforced as the national tongue while local languages were suppressed from the late 1940s until martial law was officially lifted in 1987.

If “national language” brings to mind a colonial regime that silenced local voices, then another term evokes the parallel wounds of the exiles who served that regime. The story “Healthy Sickness” is about a university student who finds such a perverse honor in her suffering that her eating disorder is described as a “battle scar.” The original text likens her “stifled pride” to the image of a 退伍老兵 (tuìwǔ lǎobīng). The term literally means “discharged veteran.”

When I translate a book, the translation choices I make are not about proving loyalty or committing to some ideological framework.

Yet in Taiwan, I came to associate the term with the Kuomintang soldiers who retreated to the island after losing the Chinese Civil War in 1949. These migrants became figures left in a historical stasis, unable to face their present while nursing traumatic loss (their nostalgic literature constitutes an entire genre). To carry this specific melancholy into English, I added two words not present in the original: “A stifled pride seeped into her words, like that of a veteran fondly stroking his scar while recounting the whistling bullets of a lost war.”

The student, Hsiao-Hua, seems proud of her own self-defeat throughout the story. The allusion to a “lost war,” then, mirrors how she sacrificed her mind and body in a grueling campaign of academic ambition, only to be abandoned in ruin.

Terao Tetsuya’s linguistic landscape expands at times beyond Mandarin to draw on Japanese and Taiwanese Hokkien. In “Hiān-Tsāi Sī Hit Tsi̍t-Kang” (現在是彼一工), a story that follows a group of friends in San Francisco, the characters watch Taiwan’s 2014 Sunflower Movement unfold from a distance. They can only take part in the protests through a relay march. The story’s title is a direct quote from the movement’s anthem, “Island Sunrise” by Fire EX.

Instead of translating the lyric to its English meaning (“Today is the Day”), I chose romanized Taiwanese. The song’s use of the native language is part of a longer tradition in Taiwan of dissent and self-assertion. For the diaspora characters, hearing the lyrics sharpens both their feelings of solidarity and helplessness. And for the English-language reader, seeing the phrase “Hiān-Tsāi Sī Hit Tsi̍t-Kang” becomes a moment where they must confront a reality that cannot be assimilated into English.

Perhaps translating the book does show where my loyalties lie—not to any simple narrative, but to the loving labor of trying to understand a place.

Early on while writing this essay, I was compelled by the idea of translation as a test of my allegiances, just like the student’s question. But in fact, this metaphor is far from how I actually experience the process. Unlike a test, there is no right answer or a way to “pass” in translation, which is an art of compromise. When I translate a book, the translation choices I make are not about proving loyalty or committing to some ideological framework. They are rather about noticing the ghosts in everyday words, learning the histories I didn’t know, and growing into a sense of responsibility.

When I first arrived in Taiwan, I was surprised to find that my students used an entirely different phonetic system to sound out Chinese characters. I’d grown up with pinyin, while they used bopomofo, also known as zhuyin. Since this difference extends to Taiwanese computer keyboards, my initial ignorance became a translation opportunity. In a Spent Bullets scene where a character’s keyboard jams while typing “ㄐ,” I kept the symbol so that this jolt of linguistic difference could also reach English readers.

Before living in Taiwan, I didn’t know what zhuyin was, nor a word of Taiwanese, nor would I have grasped the historical irony in a character wearing a Republic of China flag while trying to honor the Sunflower Movement. It took years to learn these things, and I’m still learning.

Terao Tetsuya’s Spent Bullets is not a piece of cultural diplomacy designed to make Taiwan more attractive. It is a shard of glass that reflects one author’s truth. Perhaps translating the book does show where my loyalties lie—not to any simple narrative, but to the loving labor of trying to understand a place.

__________________________________

Spent Bullets by Terao Tetsuya and translated by Kevin Wang is available from HarperVia, an imprint of HarperCollins.