Traveling on a Greyhound bus, you can disappear.

Article continues after advertisement

*

The day hadn’t yet begun as we pulled out of Detroit. We were heading to St. Louis through lashing rain under a black sky. The only sounds were the regular swish of windshield wipers and the rhythmic sucking of rubber tires on wet tarmac. It was too early for conversation. The people around me seemed weary. Some looked like they hadn’t slept in days. Others had come prepared with pillows, eye masks and blankets. The woman next to me appeared lost in her thoughts. No phone, no book, she was just sitting. I could sense she was working something out in her mind. The reading lights didn’t work and I nodded off.

When I woke from a light sleep, I could just make out the skeletons of electricity pylons and the sprawling bodies of industrial buildings through the large foggy window. Every now and then the bright lights of gas stations and truck stops veered into view, signaling food, rest, a break from the grey monotony of the highway.

As I became more awake I noted fields, the outline of scrubby trees, ads for RV campgrounds, enormous parking lots, 18-wheelers, truck dealerships, farms, phone masts, a U-Haul storage center with electric yellow windows lit from the inside, rusting CN boxcars, factories, the odd small opalescent body of water just about visible under the tungsten glow of the edgelands—a glow that dimmed with the brightening of the dawn. We passed a building whose chimney was on fire. No one seemed aware of it. The flames carried on burning in the muted landscape as we sped past.

I put away my books and my fear and bought an airline ticket so I could make the journey that seventeen years earlier had emerged from a sense of profound grief.

It was March 2023 and I was on a Greyhound bus retracing a 2,300-mile journey from Detroit to Los Angeles—a trip I had taken in 2006. As a non-driver, my only options for crossing the continent solo consist of hitchhiking, taking a train or taking a bus. For several years, I’d felt a pull to remake this journey, to revisit the motels, diners, highways, parking lots, towns, cities, suburbs and truck stops. I was curious to see how the places I had traveled through in 2006 had changed, while simultaneously catching a glimpse of the person I had been then. A ragged person running away from loss.

Marc Augé, the late French anthropologist, sees these revisited “places of memory” as opportunities to face “the image of what we are no longer.” A place can offer a palimpsest of one’s past and present: the superimposition of our current selves onto the memories we have of a place allow us to be, in Augé’s words, “tourists of the private.”

*

During the COVID-19 pandemic, I tried to satisfy my urge to strike out across the United States by immersing myself in the literature of the Great American Road Trip. My journeying would be a literary one, as I followed fictional characters and writers into temporal and spatial zones forbidden to me.

I traveled with Sal Paradise, Jack Kerouac’s narrator in On the Road, in his search for the beating heart of the artist and visionary, for transcendence, for that sense of immensity and freedom that comes from racing across a continent chasing the unknown. And there was John Steinbeck, who in 1960 drove from Long Island to the Pacific coast and back again with his poodle and documented his 10,000-mile journey in Travels with Charley. In 1934, almost forty years before Steinbeck, the journalist and author James Rorty drove from Easton, Pennsylvania to Los Angeles, interviewing people along the way and describing their working conditions in fields and factories. Where Life Is Better: An Unsentimental American Journey is an extraordinary and angry work.

“I encountered nothing,” Rorty wrote,

in 15,000 miles of travel that disgusted and appalled me so much as this American addiction to makebelieve. Apparently, not even empty bellies can cure it. Of all the facts I dug up, none seemed so significant or so dangerous as the overwhelming fact of our lazy, irresponsible, adolescent inability to face the truth or tell it.

The book that spoke to me the most was Blue Highways: A Journey into America by William Least Heat-Moon, a Missouri-born author of Irish, English and Osage ancestry. In 1978, Least Heat-Moon lost his job teaching English. On the day that he was fired, his wife, from whom he’d been separated for nine months, announced that she was now seeing “her ‘friend’ Rick or Dick or Chick. Something like that.” Least Heat-Moon decided to head off in his van across the US the very next day. “A man who couldn’t make things go right could at least go,” he wrote. I knew this feeling well: a sense that fleeing was the best way to face change and loss.

Once the pandemic began to lift and my thoughts returned to the Greyhound, I wondered how I would feel sitting in the enclosed space of a bus. Would I be imagining the vectors of aerosols from my fellow passengers as they talked? Would I be envisioning traces of the virus on my armrest tracked in from a motel reception area? The innocent and unquestioned sharing of air with other people had become infected with fear. But my desire to revisit these places and a younger version of myself became too insistent to ignore.

I needed to know what it would be like as an older woman, a less vital and sexually adventurous one, a more circumspect one, to revisit my 2006 journey and re-engage with the world in our post-pandemic landscape. I wanted to see how I would respond to the sleeping head of a passenger as it tilted towards me on the bus, how I would react to the offer of sharing a pair of headphones or a bag of crisps. Would it be met with the COVID-infected knee-jerk “No, thanks” of self-preservation and paranoia? Or the grace, humor and gratitude from the before times?

I would not only be revisiting the motels, cities, highways, parking lots, edgelands and upholstered seats of the Greyhound (that is, if they still existed)—I would also be revisiting my younger self. I would be trying to recapture Marc Augé’s “fugitive feelings…where all there is to do is ‘see what happens.’” I put away my books and my fear and bought an airline ticket so I could make the journey that seventeen years earlier had emerged from a sense of profound grief.

*

It was a cold January morning in 2006, when my husband Jason and I got to the Royal London Hospital. I knew it was dead. I had been mourning my sister Mary for eighteen months and now there was another death, but this one was inside me. The familiar jelly was rubbed onto my stomach and the nurse standing at the ultrasound machine gave me the news I was expecting: there was no heartbeat. It was my third miscarriage. I had become adept at recognizing the exact moment life ceased inside me: my morning sickness lifted, the metallic taste in my mouth disappeared, fatigue drained from my limbs and my appetite returned. I no longer retched when I smelled coffee, alcohol or frying garlic.

My husband Jason’s face wore a somber expression. We said nothing to each other for some time. There really was nothing to say. It took several weeks for us to return to those normal conversations about what we might cook for dinner, what film we might watch, which friends we might invite over, how work was going. I worried that the double punch of another miscarriage with the death of my sister could damage me for life, that I might never again experience any sort of levity or joy, that I had to accept life without children, life as a trail of disappointments and deaths.

I held these losses close and while turning them around in my mind, I decided that I needed to do something that I would not have been able to do if I were cradling an infant in my arms. I decided that what I needed was to travel, to move, to remind myself how good it felt to be unencumbered. I wanted to escape my desire for a child, and my grief, and revel in being unburdened by domesticity. I could achieve this, I thought, by crossing the United States from east to west on a Greyhound bus.

Jason gave me £1,000 to help with my trip; in 2006 that covered most of it. Then, I got out the maps. I spent weeks staring at them, reading out the names of places while working out my route. So many of the names were stories, erasures, fabrications and myths. The place names in Kentucky seemed the most visceral and evocative: Decoy, Subtle, Mud Lick, Mummie, Neon, Minnie, Mousie, Hazard, Viper and Defiance. But my route wouldn’t be taking in Kentucky: I would start in my home province of Ontario and finish in Los Angeles.

While my sister in Toronto was dying, a fictional character called Karl Jones appeared in my imagination. A no-bullshit, androgynous eighteen-year-old from Napanee, Ontario, she became my companion as well as the central character in a novel I had started writing which opens with Karl nursing her terminally ill father. After his death, Karl (like me) is grief-stricken. During her father’s final weeks, Karl’s estranged mother, Jean, has begun calling and leaving desperate messages. Karl hasn’t spoken to Jean in thirteen years. The phone calls are like guerrilla attacks: her mother is broke and wants the house in Napanee. Freed of her caring duties, angry and uncertain about her future Karl gets on a Greyhound bus and heads to Las Vegas where Jean is working as a waitress at the El Cortez. I would travel in Karl’s footsteps and stake out her friends, see where she grew up and look out the Greyhound window partly through the eyes of a smart, funny teenager. That way I could grieve and keep moving and I had something to write, a character and a plot to develop. Having a project and a plan filled the gaps left in the absence of joy and the sense of a future worth heading towards.

*

When I landed in Toronto on March 10, 2023 to begin my most recent cross-country journey, I walked under a glowering sky from the airport concourse to a bus stop where I was to board a Megabus to Napanee. Snow was coming down in large clumps and I had that awful post-long-haul flight taste in my mouth: of bad food, cheap wine, no sleep and recirculated air. And I was about to face a five-hour bus trip.

I stood next to pillar C8 in the departures area, where the Megabus app told me I would find my stop. A blizzard was whirling and I worried that my bus might not show up. Inside the airport, I found an information desk and asked the woman behind the counter whether buses would be running in this weather. She leaned forward to look out a window where wind was smearing dirty white gobs of snow across the glass. She looked at me, puzzled. “Oh, this is nothing. Nothing at all! Your bus will be fine.” I had been out of Canada for too long. I had forgotten what winter was like here.

I waited in the warmth of the airport, with one eye on pillar C8. Nearby, a young woman with three kids sat on the floor FaceTiming someone on her phone. She was crying. Her kids were playing with a luggage trolley, blocking out her tears by inhabiting their own alternate reality. The woman was begging for something, but I was too far away to hear what she was saying. A security guard showed up and squatted next to her. I could tell from his body language and the tone of his voice that he had come to offer help rather than to move her on. She was sobbing now and her phone was on the floor next to her, her face in her hands, her children ignoring what was going on. I headed out into the blizzard to stand by pillar C8, feeling haunted by this woman. She wasn’t wearing a winter coat, nor were her kids.

The bus shelter was on a paved section of the airport departures area where people were being dropped off by taxis, friends, family. It was dark now and very cold. A young guy showed up and stood next to me in the little bus shelter. He was holding one long-stemmed white rose.

“Do you know if this is the bus stop for Kingston?” he asked.

“Yes, I’m going to Napanee and I think it’s the same bus.”

“Where are you from?”

“London,” pause, “England.” You have to say ‘England’ in Canada or people will think you mean London, Ontario.

“Cool. What are you doing going to Napanee?”

I told him I was working on a book, a travel book. I hadn’t decided what I would tell people yet when they asked, which I knew they would. I am superstitious about talking about my writing. The White Rose Guy wanted to know more. I said I was writing about crossing the US on a Greyhound bus.

“Sweet,” he said. And then I got his story: he was twenty-one, had studied firefighting—structural, rather than wildfires—and he was going to visit his girlfriend in Kingston, hence the rose.

“But you’re having a real adventure,” he said.

Looking down at my phone for the live Megabus route, I noticed that the little bus icon had passed the airport and was on the way to Napanee. The White Rose Guy checked his phone and it said the same thing. We both panicked and questioned whether the bus could have shown up while we were chatting. Did we miss it? How could we have? It was dark and blizzarding, but we could see the road right next to us. By this time, it was 7 PM in Toronto, which made it 2 AM for me. I was cold and tired and worried that I’d have to conjure somewhere to sleep. Just as the White Rose Guy and I were discussing what we might do, the bus appeared, a ghostly apparition in the snow. It hadn’t passed us at all; the Megabus app was wrong.

The ride to Napanee was treacherous. Snow turned to freezing rain. High winds made the bus feel unstable on the road. The highway was littered with accidents and vehicles were stuck in snow drifts. Snowplows and large trucks outnumbered cars. Our bus skidded. I could feel ice under the wheels. There were no overhead lights so I couldn’t read, but I was too anxious to sleep. All I could do was stare out at the occasional flashing lights of emergency vehicles emerging from the white-out.

We got to Belleville at ten o’clock. An older passenger got off the bus and was greeted by a young man. Both of them in parkas. They hugged like bears.

I got dropped off just after eleven at a giant Petro-Canada station on Highway 41 bordering the outskirts of Napanee. Eighteen-wheelers were parked in rows next to a 24-hour Denny’s. I found myself in a brilliantly lit oasis in the snow, like a frozen stage set constructed to showcase a diner, a gas station, semi-trailer trucks and giant cars. Across the highway from this bright petroleum-fueled tableau and through the flying snow I could just make out the backlit Royal Napanee Inn sign. I ran across the empty road and rang the bell. Despite the late hour, someone magically appeared to hand me my room key. There was no one around, just gigantic snow drifts, sleeping trucks and neon signs designed to be seen by drivers in their cars from miles away. I flopped into bed.

*

I was woken at 7.30 in the morning with a noise that took me straight back to childhood: the scrape of a metal shovel on icy concrete. I opened the door of my motel room onto blinding sunlight, reflecting off dazzling, fresh snow. The person shoveling—or scraping—the hardened snow from the motel steps was Betty, a sweet woman in a knitted tuque embroidered with ‘I ♥ CANADA.’ She lived rent-free in the motel in return for doing jobs around the place.

I showered, dressed and headed across the highway through a maze of parked fuel trucks in the forecourt of the Petro-Canada station. All these machines looked strangely beautiful covered in glittering snow under a pure, clear blue sky. In Denny’s, I was greeted by a small sea of baseball caps and checkered shirts, and made my way to a table by a window where dust motes danced in the rays of sunshine. The talk among customers was last night’s blizzard. I looked out onto the parking lot at the polished, silver tanker trucks.

“So nice to see the sun, eh, after last night’s storm,” the waitress said as she poured my coffee.

After breakfast I checked out of the Royal Napanee Inn. I had stayed there for logistical reasons: it was the only motel within walking distance of the bus stop. My actual destination had always been the Fox Motor Inn, where I had stayed in 2006. I asked Roger, the owner of the Royal Napanee Inn, if he could call me a taxi. He needed to know where I was going and I had to come clean.

“It’s a shame,” he said. “I could have offered you a deal on two nights.”

What I didn’t tell him was that the Fox Motor Inn was where my previous trip had begun, when I had gone looking for the house of the fictional Karl Jones who, at the beginning of my novel, is working as a catering assistant. Instead, we wished each other well and I thanked him.

As I waited for my taxi in the parking lot, a guy pulled up in a Dodge Ram 1500. “You need sunglasses,” he shouted. His English was accented. Russian, maybe. He got out of his truck waving his arms frantically. “Your brain can’t compute all these rays going into your retinas.” He went on about the percentage of the sun’s rays going into our bodies and how they are processed by our minds and the damage I was doing to myself standing in this parking lot. I squinted at him as he stood against the rising sun. I was unable to comprehend what he was telling me and I needed coffee.

Having a project and a plan filled the gaps left in the absence of joy and the sense of a future worth heading towards.

I was grateful when my taxi arrived. It dropped me in front of the Fox Motor Inn, an anonymous chalet-style motel sprawled along Highway 2, a road which began its life as a stagecoach trail and was now a paved highway stretching across southern Ontario. My diary entry from 2006 also mentions a taxi journey to the Fox Motor Inn. The date was April 3, 2006, a date which was to take on huge significance the following year, though I did not know this then. There were no Ubers, so I had shared a cab to the motel with a guy a few years younger than me, in his mid-to-late thirties, handsome in a clean-cut sort of way. He asked where I was from, and I told him I was from Canada but that I now lived in England. He was from Buckinghamshire but lived in Napanee. Our driver piped up. He had come from Dorset as a teenager to work in Canada. I was the only Canadian-born person in the cab, but I didn’t live in Canada, which felt somehow very Canadian.

There were no shared taxis on this recent trip. Jim, the owner, greeted me and asked how I’d liked the Royal Napanee Inn.

“How did you know I stayed there?” I asked, confused.

“When you called me earlier to ask about an early check-in, I recognized the phone number.”

“Oh,” I replied.

“But, it’s fine. We’re friends, Roger and I. We’re both from India.”

The Hotel Wars in Napanee seemed convivial enough.

*

March can be an ugly time of year in Ontario. The snow is often just beginning to melt, and scruffy yellow patches of grass appear like small, hairy scabs. In 2006, I had arrived terribly underdressed, having forgotten that spring could be so cold. This time, I bought a puffy down coat especially for the trip. I looked like the smallest figure in one of those Russian nesting dolls, tiny and rounded. Fresh snow was piled high on every surface, from spindly tree branches to gabled roofs like towers of marshmallow fluff. A big blue sky hovered above everything.

After checking into the Fox, I walked along the main road into town. The outskirts hadn’t changed much, but as I approached the center, I noticed many of the cafés and restaurants I remembered were no longer there, although a couple of new ones had sprung up. The frozen banks of the Napanee River looked the same: like jagged teeth around the liquid mercury tongue of the water.

*

I was sad to see the Superior Restaurant & Tavern on Dundas Street had closed. The place had been decorated with larger-than-life photomurals of autumn woodlands, waterfalls and undulating farmland. Moose antlers, taxidermy, dusty Christmas decorations and knick-knacks had made their way into every corner. Back in 2006 the owner had greeted me with the Greek welcome, tikanis. There had been only one other customer that night: a man eating alone. I remember ordering the vegetarian moussaka.

The other diner, who was at a nearby table, shouted, “Good choice! Not like that Kraft stuff, that white stuff,” he mysteriously added.

After we’d both eaten our meals in silence, he approached and told me how he used to be into photography but now that he was blind, he had to see what everyone else sees in his own head. He asked how I’d liked my moussaka and whether I was a tourist. Before I could answer, he said that there were better months to be a tourist in Napanee.

“My timing is always terrible,” I said.

He replied, “Your timing is beautiful because I got to talk to you,” and then turned and walked out.

As I left the Superior that night, snow began to fall, great huge flakes of it.

*

The Superior Restaurant & Tavern has now become Touch of Class Fashions boutique, “a ‘one stop shop’ for women of all ages filled with smart casual wear, resort, formal wear, shoes, jewelry, handbags and accessories.” There was no one there to tell me my timing was beautiful.

I wandered around Napanee in the cold, taking photographs until my fingers froze. At Conservation Park, the GREATER NAPANEE sign read greater for many reasons. I marveled that someone had presumably been paid to provide branding of such extreme vagueness. Two joggers in shorts and sneakers were heading in my direction. I was wearing boots and could easily navigate the snowbank, so I scrambled aside to give them space. They both effusively huffed a very Canadian “thank you.” I walked along County Road 2, the first paved road in Canada, which joins Kingston and Toronto. It turns into the town’s main street, Dundas Street, where it crosses the Napanee River. There were fewer restaurants and bars, fewer places where people could gather. This would turn out to be a portent of what was to come.

__________________________________

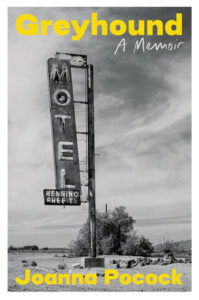

Excerpted from Greyhound: A Memoir by Joanna Pocock. Copyright © 2025. Available from Soft Skull Press.