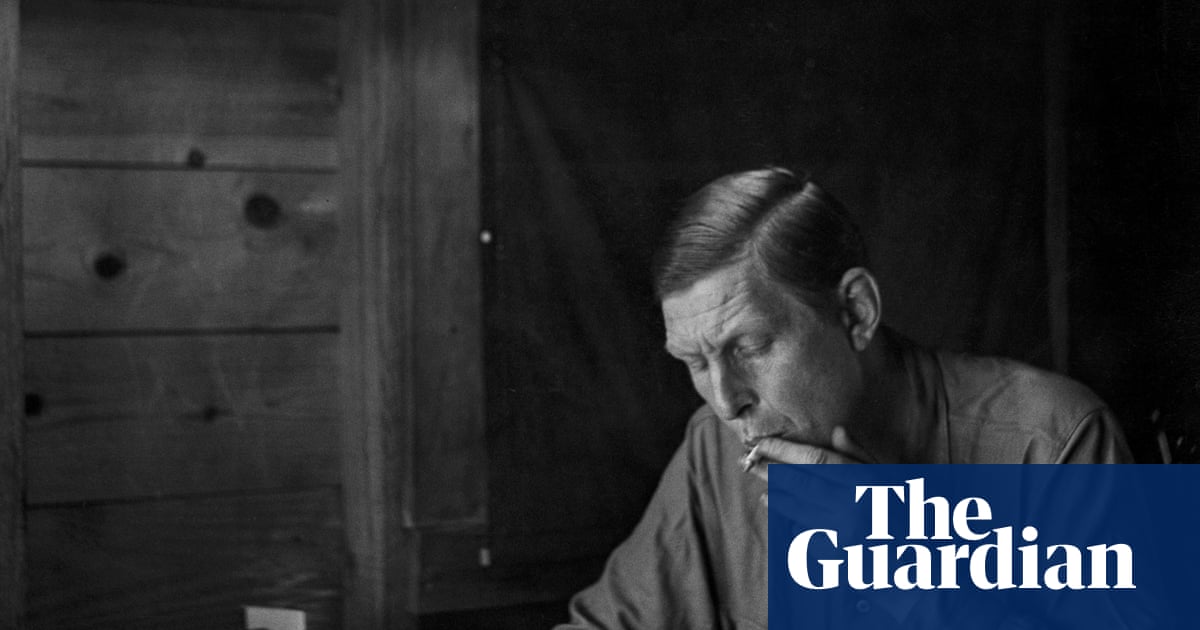

A “once in a century” discovery of a cache of long-lost letters has revealed how the English poet WH Auden developed a deep and lasting friendship with a Viennese sex worker and car mechanic after the latter burgled the Funeral Blues author’s home and was put on trial.

York-born Auden, a prominent member of a generation of 1930s writers that also included Christopher Isherwood, Louis MacNeice and Stephen Spender, described his unconventional arrangement with the man he affectionally called “Hugerl” in the posthumously published poem Glad.

“Our life-paths crossed,” it reads, “At a moment when / You were in need of money / And I wanted sex”.

But little was known about the life and full criminal history of Hugo Kurka until Auden scholar Helmut Neundlinger mentioned his name in an Austrian TV programme occasioned by the 50th anniversary of the poet’s death in 2023.

The next morning, Neundlinger received an email from a woman who had grown close to Kurka and his wife, Christa, after they settled in the Lower Austrian countryside in the 1990s and had inherited their belongings after they died of cancer within a year of one another, in 2012 and 2013.

She showed Neundlinger 100 letters that Auden had sent to his lover, some of them also addressed to his spouse. “It’s a once in a century find, the kind of thing a literary historian can only dream of,” says Sandra Mayer, a cultural historian at the Austrian Academy of Sciences who has spent the last two years digitising the letters with her colleague Timo Frühwirth, and went public with the discovery last week.

Spanning roughly 10 years between the early 1960s and 1970s, they are written in enthusiastically colloquial – if frequently misspelt and agrammatical – German.

Auden had spent time in Berlin in the late 1920s and later entered a marriage of convenience with the bisexual daughter of the novelist Thomas Mann, Erika, to help her gain British citizenship and flee from the Nazis. After a stint in the US, he settled in the Austrian town of Kirchstetten, where he lived until his death in 1973.

The public-school educated poet was in his mid-50s when he met the working-class twentysomething. “Glad our worlds of enchantment / Are so several / Neither is tempted to broach”, Auden later wrote in his poem. “I cannot tell a / Jaguar from a Bentley / And you never read”.

Their relationship appears reminiscent of the famed bond between painter Francis Bacon and his lover George Dyer, a gang-affiliated East End petty crook in London. But whereas Dyer breaking into Bacon’s apartment is a modern myth compounded by the Daniel Craig-starring biopic Love Is the Devil, in Auden’s case it was true.

Though Kurka had completed an apprenticeship and was in work, he was struggling for cash. When Auden lent him his Volkswagen Beetle before embarking on a trip to the US, the young man and two accomplices used the vehicle to carry out a series of car burglaries, culminating in a break-in at the poet’s own home.

They were arrested after a police chase, found in possession of stolen goods worth 34,000 Austrian schilling (the equivalent of about €20,000 today) and put on trial.

Since the car was registered in Auden’s name, the court case risked making public the relationship between the young criminal and the writer.

after newsletter promotion

Auden enjoyed a special status in Austria at the time, says Neundlinger, a curator at the WH Auden Museum in Kirchstetten. “He never hid his homosexuality. But unlike Christopher Isherwood, he was never an activist for gay rights.” Enjoying a high degree of respectability as a professor, the English writer also regularly visited the local church. “He blended in and tried to live a normal life.”

Since same-sex acts were still a criminal offence in Austria, Kurka’s trial risked stirring up controversy around the poet, who had won a Pulitzer in 1948 and was in close contention for the Nobel prize in literature at the time.

An innuendo-filled article in Austrian newspaper Kurier on 16 October 1962 did not name Auden, who had become a dual US-UK citizen in 1946, but referred only to “one of those Americans who got stuck in old Europe with its different, much freer way to live and let live”.

Instead of testifying against Kurka, Auden asked his own longstanding lawyer to recommend a good advocate to defend him. Kurka was sentenced to 15 months in prison, his wife to eight.

“The whole episode was a turning point in their relationship, and a positive one,” says Neundlinger. “Auden did not know whether Kurka would give away intimate information when interviewed by police – the fact that he didn’t seems to have strengthened their ties.”

“Both learned a lesson,” Auden wrote in Glad. “But for which we might still be Strich und Freier” – translated as “streetwalker and john”. None of Kurka’s letters to Auden have been recovered, but in those the poet wrote from trips to New York or Berlin back to Vienna, he is warm and candid. The older man sent Kurka and his wife money to pay for flights to visit him, as well as for English lessons, and complained about feeling abandoned by his partner, the American poet Chester Kallman. “I feel a little bit lonely and wish you were here,” he wrote in November 1964.

“There may have been an idea that their relationship was purely sexual or transactional in nature”, says Neundlinger, but “these letters show they enjoyed a long and intense friendship”.