The title of Chloé Caldwell’s memoir, Trying—its potential ick implications (someone “trying” to get pregnant)—is something Caldwell is well aware of. And yet, buck it as she might, few words more accurately describe the intense desperation that can set in for someone hoping to conceive.

For the person who will carry the baby, it can become a part-time job—ovulation monitoring, supplements, fertility appointments, blood tests, pharmaceuticals, online groups, procedures, and, as people often maddeningly suggest, trying to somehow simultaneously chill out and emit good vibes. At one point early on in Trying, Caldwell reads a newsletter that posits “the brain of someone trying to get pregnant should be studied.” Caldwell: “Consider this book to be that brain.”

Because unlike the narratives often fed to us in feel-good movies or people’s social media posts, despite everything being physically “perfect,” as she’s often told, Caldwell doesn’t get pregnant in six months—or a year. It’s taking long enough people in her life have learned to stop asking. It’s eating up her life. On her “unexplained infertility,” she says that “if something is unexplained, isn’t it a writer’s job to attempt to explain it? Or at least try?”

A book like Trying could have operated like the much-lauded Linea Nigra by Jazmina Berrera (translated by Christina McSweeney)—and indeed Trying similarly has short often page-long pieces of prose that string together like a row of fluttering flags. Yet Caldwell, in the frenetic holding pattern of pre-maternity, and pushes against the frequently employed methods of writerly triangulation between the speaker, her desire(s), and some third apparently disconnected thing that can be elegantly woven in (groundhogs or opaque philosophy, for example).

Instead, Caldwell writes from her life and copious knowledge about fertility, about “trying.” Then, after the revelation of a betrayal so severe she wonders if her body was somehow rejecting her husband’s sperm, her life explodes. “How does a book about irresolution end?” Caldwell asks in the final portion of the memoir. “What is the reader owed? What is the writer owed?” and, pointedly (something to which I and anyone writing personal nonfiction desperately relates): “If you’re writing about your life in real time, are you inherently fucked?”

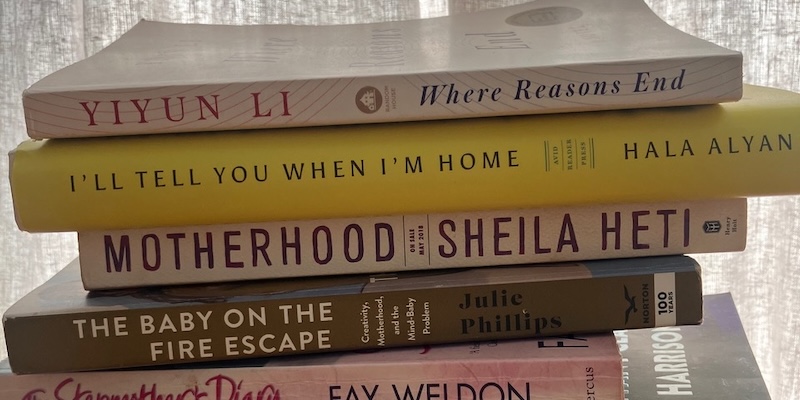

Caldwell tells us about her to-read pile: “My nightstand is a stack of books I put together to read when I was considering ‘outlaw mothers’ for the column I’m writing for The Believer. Super fun to scan my bookshelves to find which mother protagonists are outlaws, meaning they put their own personal fulfillment before their children’s.”

*

Yiyun Li, Where Reasons End

Where Reasons End was written in the aftermath of Li’s older son’s suicide, and she has talked about how this novel was part of her grieving process. Helena Duncan writes in Chicago Review of Books,

The book is not a mystery: the mother doesn’t search for missed clues, or attempt to come to a conclusion about why Nikolai has chosen to end his life. Instead, the two talk to each other as they did in his life, and these conversations, which she describes as a kind of contract that they have both entered into, provide her with solace in the face of his absence.

Hala Alyan, I’ll Tell You When I’m Home

Alyan was recently interviewed here on Lit Hub by Sahar Delijani. Alyan says of I’ll Tell You,

in some ways, it felt more natural to lean into all of the parts of myself I find ugly, complicated, messy—parts that have caused harm and been harmed—than to tell only a little. But truth can also become a little bit addictive, right? The more I told, the more I wanted to tell. And in that way, it actually became easier to just commit fully rather than inch around it.

Sheila Heti, Motherhood

Lara Feigel writes at The Guardian, “Sheila Heti’s book seems likely to become the defining literary work on the subject [of motherhood], perhaps most of all because as a novel, replete with ambiguity and contradiction, it refuses to define anything, and certainly not the childlessness that provides its subject or the motherhood that provides its title.”

I’m still puzzled by the many critics who were grumpy about this book. It kept me absolutely rapt for its nuance and, often, absurdity. (I could read pages and pages of the protagonist throwing coins in the I Ching method to learn from god if she should have children.)

Julie Phillips, The Baby on the Fire Escape: Creativity, Motherhood, and the Mind-Baby Problem

The Baby on the Fire Escape considers artists and writers like Audre Lorde, Doris Lessing, and others. Lauren LeBlanc writes at the LA Times,

Juggling motherhood and creative work can leave one feeling like an iconoclast and a failure all at once. “The Baby on the Fire Escape,” Julie Phillips’ tremendous group biography and exploration of what she identifies as a ‘mind-baby problem,’ focuses on women of the mid-twentieth century onward, when ‘motherhood went from being an accident and obligation to being a choice.’”

Fay Weldon, The Stepmother’s Diary

Emma Hagestadt writes at The Independent that Weldon “turns her brainy gaze on the muddle of modern family life. The diary of the title belongs to Sappho, a young playwright married to a widower 19 years her senior, and stepmother to his two children….Using the diaries as her starting point, Weldon constructs a funny, frank account of family relationships.”

Tiffany Clarke Harrison, Blue Hour

“The unnamed narrator of Harrison’s debut novel is a thirty-four-year-old Black Japanese photographer and teacher who is struggling with infertility and an increasingly complicated relationship to motherhood,” says Kirkus about Blue Hour. “The narrator blames herself for a life-altering family tragedy and struggles to believe she deserves good things, including, and perhaps most especially, a child.”

Claire Lynch, A Family Matter

A Family Matter is, as the title suggests, about a family, but forty years apart: in 1982 and 2022, with the future doling out reveals at the novel’s beginning.

“Readers will find themselves catching their breath at the truth and beauty of many of Lynch’s sentences. Through her characters, Lynch shows her audience that love between people may change or plateau or grow by leaps and bounds, but as long as they want to keep it, they will,” writes Jennifer M. Brown at Shelf Awareness.

Sue Miller, The Good Mother

Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, in his spoiler-filled 1986 review at the New York Times, finds Medea an appropriate mythological equivalent to Miller’s protagonist—and wonders why she doesn’t exact similar violence:

The answer to my question was supplied by a couple of shrewd women I know. They pointed out what I’d failed to recognize, that ‘The Good Mother’ is really an attempt to dramatize the common female fantasy that if a woman lets herself go sexually she loses control of her world, including her ability to mother.

Here’s to shrewd women.

Kristin Kovacic (editor), Lynne Barrett (editor), Birth: A Literary Companion

“Birth: A Literary Companion collects the work of fifty accomplished writers to guide new parents through this complex emotional terrain,” states the jacket copy for this anthology that includes Toi Derricotte, Alicia Ostriker, and others. “Here, a curious reader can find a frank, funny essay about breastfeeding, a vividly accurate story about labor, or a tender poem about the terror of holding a newborn child.”

Hila Blum, How to Love Your Daughter (trans. Danielle Zamir)

“Told from the perspective of mother Yoella in a series of short vignettes, the novel opens with a scene of her hiding in the bushes, spying on her grown daughter Leah,” writes Lauren Gilbert for the Jewish Book Council. “The rest of the novel, a loose collection of memories out of chronological order, follows Yoella’s attempt to understand what led to her beloved daughter’s self-imposed estrangement.”